New Delhi: A casual challenge from her brother changed Shailaja Chandra’s life. In Mussoorie, where he was training for the Indian Foreign Service, he teased her about working at the advertising agency J Walter Thompson: “You can be sacked any Monday from this private job. Don’t you want to do something at the national level? You can’t do it.” A year later, in 1966, she proved him wrong.

It was no mean feat. Women were even rarer in the civil services then than they are today, and Chandra was one of just seven women in a batch of 140 IAS officers. The UPSC world she entered was unrecognisable from today’s. There was no preliminary stage, and five written papers followed by an interview decided her fate. Coaching institutes didn’t exist, and the competition was less cutthroat— but only for those who belonged to an invisible club.

“The exam was categorised into three parts — IAS, IPS and central services — and the papers were designed according to the service you opted for. Back then, those who sat for the exam mostly came from privileged backgrounds, urban areas, and top universities. Speaking and writing in English came easily to them,” said the retired IAS officer of the 1966 batch. “Now the exam has been completely democratised. You could be from any language background, any university, and still make it.”

From privilege to parity, the UPSC casts its net wide today. Its story over the last century is one of constant churn — of reforms and resets, protests that forced change, and milestones that redefined the idea of who could aspire to govern India.

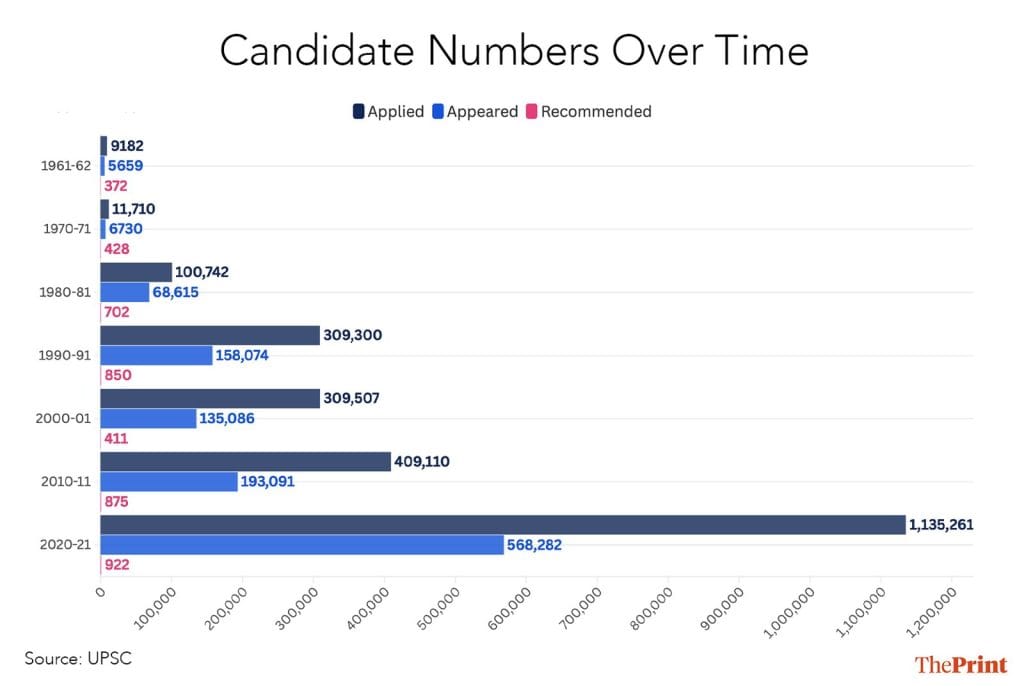

Established in the colonial era, the Union Public Service Commission is entering its 100th year. And as it went from a privileged preserve to a test of ‘merit’, its journey has mirrored India’s own transformation. And yet, UPSC symbolises the India that is also changeless. Through the socialist planned economy era, liberalisation, the explosion of the private sector and IT industry— the lure of a UPSC job has remained stubborn. The institution changed shape over time, but Indians’ obsession with it has ballooned exponentially. What began as an essay-heavy test for a few thousand privileged candidates in the 1960s is now a mass elimination race for over 10 lakh aspirants each year.

“Now it has become an obsession of a different kind. It is almost like a live-or-die situation. The chances of making it to the services is really very slim—0.2 per cent make it,” said Chandra.

In 1961, there were 34,000 applicants. Today, more than 10 lakh aspirants compete to get in. But the number of seats has increased from a few hundred in the 1960s to only about 1,000 now.

Born as a colonial tool and reframed as a democratic aspiration, the exam has been rewired again and again — through committee recommendations, reforms, and protest. From the overhaul of general knowledge papers to the introduction of the controversial ‘elitist’ Civil Services Aptitude Test (CSAT), which set off mass protests in 2014, to recurring battles over language, age limits and attempts, it has always been a site of contestation.

The interview was very, very important. It was the only place where you could judge a person’s suitability. If I was to change anything, I would give much more importance to the interview

-Shailaja Chandra, retired IAS officer

What was once a set of five papers has grown into four general studies papers, an ethics paper, an optional subject, and the CSAT. With expensive coaching classes, years spent trying and failing, and constant uncertainty, it’s a test of endurance.

But the story of UPSC is not just about an exam. It’s about how India defines merit, opportunity, and fairness.

“Safeguarding the credibility of the examination process remains our foremost priority,” said UPSC chairman Ajay Kumar, speaking on the evolution of examination reforms. “The UPSC examination is not merely a test of knowledge and aptitude, but also of character. We are committed to ensuring that it continues to be fair, transparent, and capable of selecting the finest human resources for the noble task of nation-building.”

Also Read: 73 Prelims, 43 Mains, 8 interviews—this 47-year-old won’t stop until he is a civil servant

Indianising a British service

It all began as a colonial project of the British to rule and manage the vast Indian population. The demand and priority, at that time, was control and compliance. And there was broad agreement on one point: Indians themselves were not welcome. When the Indian Civil Service (ICS) was established in 1854, its competitive exam was held only in London, far beyond the reach of most Indians.

At the time, it was not particularly elite either. The early debates centred on who should be eligible — men of “higher academic maturity” or younger boys groomed in elite public schools. In 1876, the maximum age was cut to 19, tilting the scales toward British-educated schoolboys.

“The reduction of the age was not a mere alteration of detail; it was an essential change of principle. Instead of giving to India men who have received a finished education, it gives half-educated boys specially trained for an Indian career,” Deepak Gupta wrote in his book: The Steel Frame: A History of the IAS.

But Indians wanted in and the wall wasn’t impenetrable. In 1863, Satyendranath Tagore became the first Indian to crack the ICS. His success proved it could be done, however stacked the odds. The demand for the “Indianisation” of the ICS also grew louder, led by the likes of Dadabhai Naoroji and Surendranath Banerjea. Their argument was that Indians should help govern their own land.

“Either the educated natives should have proper fields for their talents and education opened to them in various departments of the administration of the country, or the rulers must make up their minds, and candidly avow it, to rule the country with a rod of iron,” said Dadabhai Naoroji in a speech before the East India Association in London in 1867.

In 1922 the exam was held in Allahabad, and many Indians appeared for it. Before that it was held only in London, which reduced the chances for Indians to get into the civil services

Sanjeev Chopra, former director of LBSNAA

By the early 20th century, the situation was not too different from today: the number of Indian graduates was rising, but jobs for the educated middle class were scarce. The ICS exam became the bastion many wanted to break into — a narrow door to security and influence. To address the clamour, the Islington Commission was set up in 1912 to look at bringing more Indians into the service. It eventually recommended that 25 per cent of posts be filled in India, albeit by nomination. But it was the Montagu-Chelmsford reforms in 1919 that really paved the way for a breakthrough. In 1922, the ICS exam was held in India for the first time.

“It was the biggest change in those times. In 1922 the exam was held in Allahabad, and many Indians appeared for it. Before that it was held only in London, which reduced the chances for Indians to get into the civil services,” said Sanjeev Chopra, retired IAS officer and former director of the Lal Bahadur Shastri National Academy of Administration (LBSNAA) in Mussoorie.

But the debates continued over the right age, education standards and fears of overcrowding. That led to the creation of the Public Service Commission of India in 1926.

“The Indianisation of the ICS, gradually increasing the number of Indians in the service, marked a shift toward a more inclusive system, setting the stage for post-independence reforms,” wrote Deepak Gupta in The Steel Frame: A History of the IAS.

But in newly independent India, the very existence of the ICS and the Public Service Commission seemed perilous for a while.

Remaking a ‘colonial relic’

Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru had grave reservations about the ICS.

“The Indian Civil Service is neither Indian, nor civil, nor a service,” he wrote in Glimpses of World History (1949).

In the run-up to freedom, too, this had caused well-documented clashes between him and Sardar Patel, who agreed with former British Prime Minister Lloyd George’s view that the ICS was the “steel frame on which the whole structure of our government and of our administration in India rests.”

As the transfer of power drew near, Patel was determined to Indianise the services once and for all. One of the first steps was giving them a new name: the All India Services. But not everyone was convinced they should survive. In a 10 October 1949 Constituent Assembly debate, PS Deshmukh called the ICS “a remnant of the days of our slavery” while M Ananthasayanam Ayyangar dismissed it as a “heaven-born service of the previous regime.” Others argued officers were overpaid, and that it was wrong for the government to shower privileges when, as Ayyangar put it, “we have not been able to give a guarantee for food and clothing to the ordinary masses.”

When [a city] child attains the age of three or four years, he can learn many things in the school, in the bazar, which a country boy who has passed the eighth class cannot learn. When competition is held by the Public Service Commission, the same type of questions are asked

-Chaudhri Ranbir Singh, member of the Constituent Assembly, in 1949

It was in this debate that Patel delivered the speech which would define the civil services for independent India.

“There is no alternative to this administrative system… The Union will go, you will not have a united India if you do not have a good All-India Service which has the independence to speak out its mind,” he said. “Remove them and I see nothing but a picture of chaos all over the country.”

At the same time, there were also debates in the Constituent Assembly about the selection authority. Members argued about how fair the Public Service Commission could be, given the rural-urban divide, the preference for English-speaking elites, and the low representation of minorities and “Harijans” in the ICS thus far.

“When [a city] child attains the age of three or four years, he can learn many things in the school, in the bazar, which a country boy who has passed the eighth class cannot learn. When competition is held by the Public Service Commission, the same type of questions are asked,” said Chaudhri Ranbir Singh, advocating for rural reservations.

But it was the concept of overriding “merit” that prevailed.

“We must for the purpose of selecting men for the services recognise the principle of merit, and we must recognise the necessity of creating a Public Service Commission,” Raj Bahadur told the Assembly on 22 August 1949.

And so, the All India Services were formalised under Article 312 of the Constitution, adopted on 26 November 1949. Alongside this, the successor to the colonial Public Service Commission — the UPSC — was enshrined in Articles 315 to 323.

But the questions over representation, age, privilege, and fairness never quite went away. Since the 1970s, various expert committees have recommended reforms to make the system more inclusive, but at times, these efforts have backfired.

Also Read: IAS seeing progress on gender parity—1 of 5 secretaries at Centre are women

Committee-driven reforms

The whole concept of a preliminary examination— the dreaded elimination round— is only a few decades old. Until the late 1970s, lakhs of aspirants went straight into the mains, overwhelming the system with answer sheets and making evaluation chaotic. UPSC needed a way to sift the serious candidates from those just trying their luck.

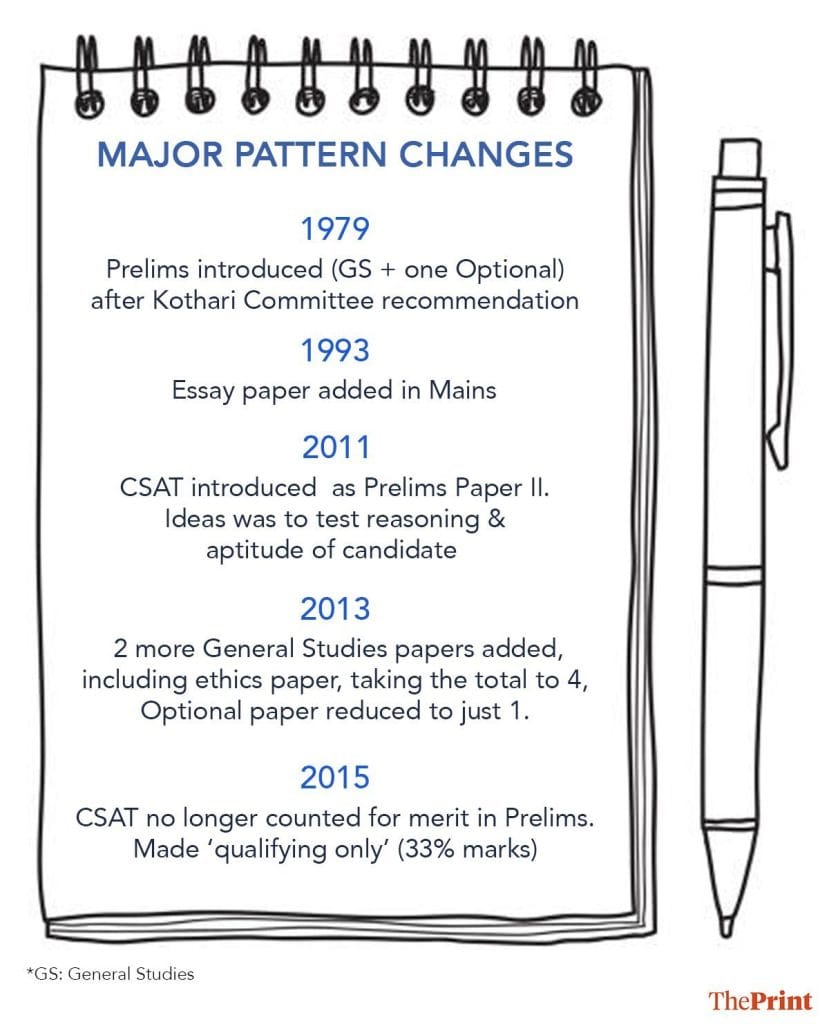

That’s when the Kothari Committee of 1976 stepped in, recommending a screening test to whittle down numbers. Its proposal gave birth to the prelims in 1979, a filter that reduced candidates to around ten times the available vacancies. Candidates called for final interview should be only twice the number of vacancies, it noted.

Another reform at this time was standardising the exam across services; earlier, IAS, IPS and other services had different papers.

“When I gave the exam, that was the first year when the Kothari Commission report was implemented. The same kind of exam was given for everyone for the first time,” recalled Anil Swarup, a former IAS officer from the 1981 batch.

Over a decade later, in 1993, it was decided that though the implementation of the Kothari Commission’s recommendations had been effective, there was room for improvement. This led to the formation of the Satish Chandra Committee, after which an additional essay paper was introduced in the mains to test clarity of thought and expression.

Other committees followed. The Alagh Committee in 2001 looked at the kind of officer India needed — not just knowledgeable, but analytical, practical and willing to take initiative. The Hota Committee of 2004 suggested that aptitude tests should be introduced for selection. This idea didn’t take root then, but when it finally crystallised, it turned into a major flashpoint.

The biggest protest

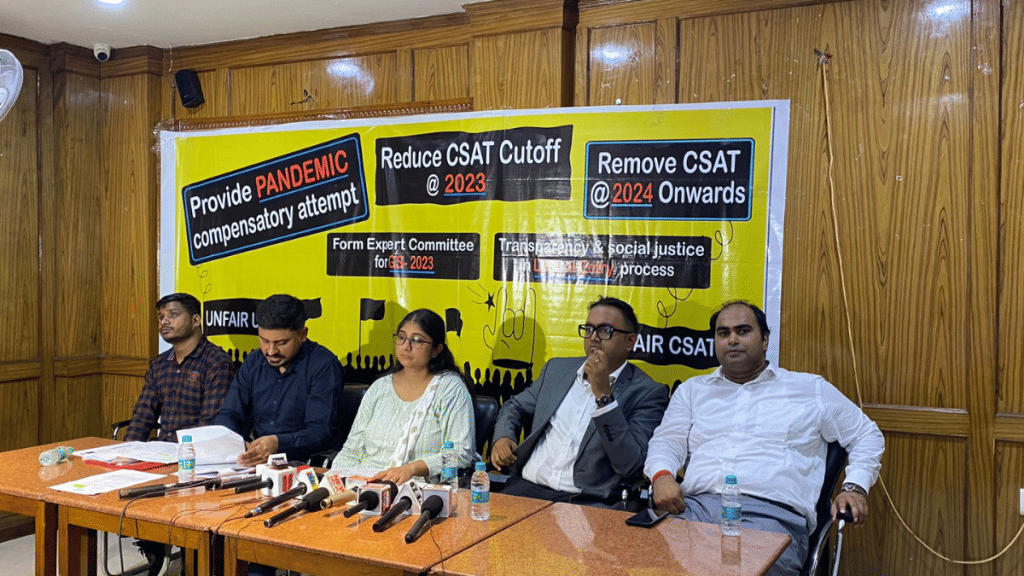

Not all changes came from expert committees. Some key reforms came from the streets—from the lungpower of protesting UPSC aspirants, to be precise. In 2014, anger over a new aptitude test spilled out of exam halls and onto roadside dharnas in Delhi.

The discontent started brewing in 2011, when UPSC replaced the optional paper with the Civil Services Aptitude Test (CSAT). Humanities and Hindi-medium students said it gave engineering graduates an unfair edge. In 2014, this resentment erupted into the biggest protest in UPSC’s history.

Nilotpal Mrinal, who had started his UPSC preparation in 2008, was among those blindsided. The new CSAT paper upended the three years of preparation he had already put in. In 2012, he cleared prelims but fell short in mains, and once again the battle with CSAT began.

“Before 2011, the UPSC exam was divided into two sections: General Studies and optional. Both came under merit. But in 2011, the optional was replaced by CSAT. Frustration turned into anger and then into protests,” he said.

It was unfair to us, it didn’t give everyone an equal playing field. The exam was biased toward engineering students. Many talented people failed in CSAT

-Nilotpal Mrinal, author and former UPSC aspirant

From 2011 to 2013, according to Mrinal, fewer Hindi-medium aspirants cleared the prelims. Yet among those who made it to the mains, the majority had Hindi as their Indian language paper.

As anger bubbled over, Mrinal, now a successful author, was at the centre of the protest movement, including marches from Jantar Mantar to the Prime Minister’s residence and a nine-day hunger strike.

“It was unfair to us, it didn’t give everyone an equal playing field. The exam was biased toward engineering students. Many talented people failed in CSAT,” he recalled, flipping through old protest photos. He also pointed out that engineers make up “nearly 65 per cent of those who enter the civil services” but usually choose humanities subjects like sociology or political science as optionals “because these are considered scoring”.

Mrinal claimed nearly 400 MPs came out in support of the protesting aspirants, and that leaders from across the spectrum — Ram Vilas Paswan, Lalu Yadav, Murli Manohar Joshi, Mulayam Singh — raised the issue in Parliament. Multiple meetings were held with the UPSC chairman and DoPT Minister.

“The stage was open to every political party but it was we who were leading the protest. NSUI to ABVP, every student party came to support us,” said Mrinal.

The hub of the protest was Mukherjee Nagar, home to Hindi-medium aspirants, while in Rajinder Nagar, dominated by English-medium candidates, things were calmer.

As the pressure mounted, the central government announced that CSAT would only be a qualifying paper in the UPSC exam. While students needed to pass it, the score would not be added to the final results of the preliminary exam. This assuaged the students and the protest ended. However, to this day, there are widespread complaints about the paper’s difficulty and its status as “an eliminating paper” rather than a “qualifying” one.

Age, attempts, ‘ethics’

Some other changes have been better received. In 2013, the number of optionals was reduced from two to one, and an ethics paper was introduced as General Studies IV.

For aspirants like Ketan (he doesn’t use a last name), who was preparing for optionals in public administration and sociology, it meant re-strategising his studies, but it worked out well for him.

“They introduced the ethics paper as a new paper, and people were questioning it a lot. But after the UPSC uploaded a sample question paper to show aspirants what kind of questions would be there, I remember that 60 percent of the actual paper was the same as the sample,” said Ketan, who got a rank of 860 in 2015.

By giving a paper, a person does not become ethical. Ethics is imbibed. The attributes required for IAS are leadership attributes… yet you do not test his attitude, nor do you test his leadership skills

-Anil Swarup, a former IAS officer from the 1981 batch

Swarup, however, questions whether scoring potential has replaced the real purpose of the papers. Or whether the exam is even a reliable predictor of success as a civil servant.

“By giving a paper, a person does not become ethical. Ethics is imbibed,” he said, further arguing that good memory and reasoning skills only go so far. “The attributes required for IAS are leadership attributes…(yet) you do not test his attitude, nor do you test his leadership skills.”

For Swarup, separate test for IAS and IPS that would incorporate psychological assessments of leadership potential might be better metrics to go by.

Shailaja Chandra, too, questioned the overload of trivia in the general studies paper. “The general studies papers have become unnecessarily heavy. They test so many facts and figures which, frankly, have no bearing on how you perform in the service,” she said.

Interviews should get more weightage than written tests, according to her: “The interview was very, very important. It was the only place where you could judge a person’s suitability. If I was to change anything, I would give much more importance to the interview.”

The commission, however, has tried to upgrade its processes in other ways — from reducing the long gap between prelims and results to introducing a smoother online portal for applications and notifications. It’s also deploying AI for faster evaluations and has developed a face authentication app to reduce impersonation and fraud at exam centres.

The rules on age and attempts have changed time and again over the decades as well, often in response to pressure from aspirants and political lobbying. The upper age limit, cut to 19 in 1876, inched to 26 and then 30 in the decades after Independence, before going up to 32 in 2014. The number of permitted attempts moved from four to six for the General category that same year. The matter still isn’t settled. Former RBI governor D Subbarao has even suggested raising the age limit to 40 while cutting back the number of attempts.

But not all changes in UPSC’s journey came from reforms or protests.

Also Read: Rejected in UPSC interview? There’s now a shot at an attractive second life

‘You sometimes need the disease…’

Some gaps in the UPSC have been exposed by gross irregularities and abuse of the system by those who cleared the exam — whether it was IAS officer-turned-actor Abhishek Singh allegedly ‘faking’ a disability certificate, Pooja Singhal accused of looting rural development funds, or Safeer Karim found cheating with a Bluetooth device in the mains after scoring high in the ethics paper.

Once in a while, cases like these trigger a systemic shake-up. One such was the Pooja Khedkar scandal in 2024. As a probationary IAS officer, Khedkar was found to have used fake caste and disability certificates to get through the exam. The case went to court and forced UPSC to tighten checks amid criticism over loopholes in vigilance.

Khedkar’s candidature was cancelled and she was permanently debarred from taking the exam again, but the case exposed gaps in the system itself. In the wake of this incident, UPSC received at least 30 complaints of similar misuse and has updated its systems to flag false claims — from name changes to forged quota certificates. DoPT and LBSNAA have also begun working on stricter verification during training. For years, documents were taken largely at face value; now candidates must upload caste, disability, and education certificates at the prelims stage rather than after qualifying for mains.

Shailaja Chandra called the case an “absolute aberration” but admitted it had an upside.

“I did get this impression that because of Pooja Khedkar, the supervision, the nigrani, has gone up enormously, which is excellent,” said Chandra. “You sometimes need to get a disease for the cure to come.”

This is the first article in ThePrint series UPSC@100.

(Edited by Asavari Singh)

They (UPSC recruits) are the people who keep killing India with third-rate, puke-worthy socialist schemes to keep their political masters in power. If India wants to become a developed country, then the brainwashing of the recruits with communist mouthpiece ‘The Hindu’ must be stopped. Hence, UPSC should recruit only those who hold views that are the opposite of what ‘The Hindu’ mentions in the newspapers.

What socialist schemes can you please mention? So schemes that can help people become capable and get access to basic services are “puke worthy”? Please describe an alternative to these schemes that can work especially for a country with 90% informal sector. What might they be? How will you implement them? Wait let me guess one such scheme that I have in my mind right now that would give more money to the rich. That would be one scheme right? Stop living in a delusional world and start to understand that schemes are important for the betterment of the society and reducing inequality. Lol when poor get benefits “Ahh Socialist policies it is our tax money” but when rich get tax cuts and their wealth increases ten folds which has happened “Wow such great people”.