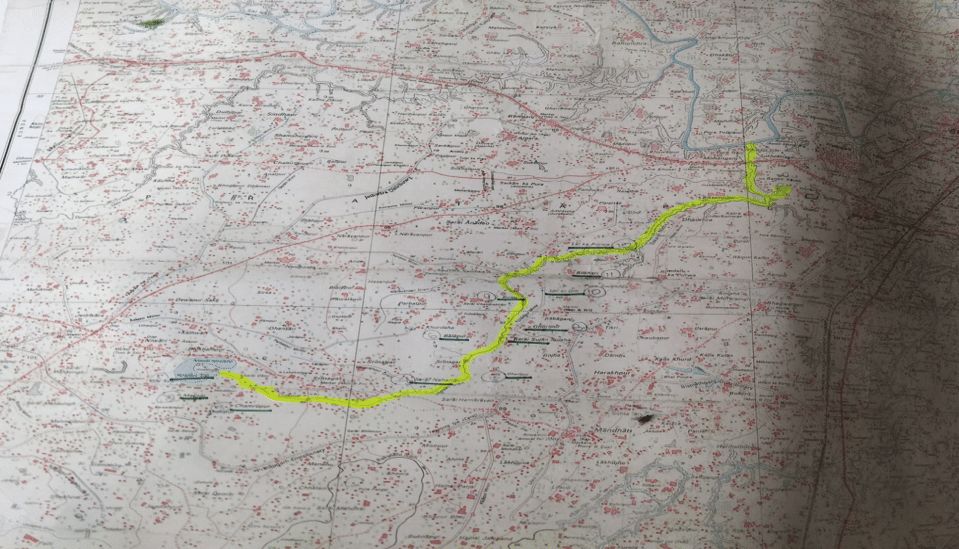

Pratapgarh: Two villagers, an environmentalist, and two district officers went to the irrigation department to search for a river they had lost. They pored over old topographical maps looking for the Sakarni River, which once flowed through 20 villages in Uttar Pradesh’s Pratapgarh district. That was nearly a year ago. Now, the seasonal tributary of the famous Sai River is flowing again.

The determination of Pratapgarh’s residents and the ingenuity of its district officials, who tapped into the much-maligned Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (MGNREGA) for funding, made this revival possible. The Sakarni had nearly dried up into a puddle after decades of silt accumulation and farmland encroachment, reduced to a faint memory among villagers. Until Ajay Krantikari, a local environmentalist, decided to do something about it.

“Our district is home to eight rivers, one of which is the Ganga itself. It was our duty to never let a river run dry in the home of the Ganga (jis desh mein Ganga behti hai, wahan dusri nadi ko kaise marne dete),” said Krantikari.

A proposal to restore the river, presented to the district administration last October, became a project involving over 20 villages when then-chief development officer Navneet Sehara decided to utilise the MGNREGA scheme for the Sakarni’s revival. His plan worked—30,000 people worked for two months to clear encroachment and revive the river.

According to Krantikari, Pratapgarh DM Sanjeev Ranjan “secured an allocation of Rs 1.35 crore for the river restoration initiative, which began in November 2023 and culminated in June 2024.”

The 28-km long Sakarni now flows freely through Pratapgarh and has paved the way for the restoration of other lost rivers in the district. It is the district’s first river rejuvenation project, with similar projects being carried out through MGNREGA across Uttar Pradesh.

“For any conservation project to be sustainable in the long run, you need to involve the people. The administration can pitch in but at the end of the day, the locals will use it, store it, and conserve it,” said Ranjan, the district magistrate.

For any conservation project to be sustainable in the long run, you need to involve the people

How the rejuvenation happened

Krantikari was riding his bike near Lalganj village when he crossed the ‘Sakarni’ bridge. He had taken this route countless times before. But for the first time, he stopped to dwell on how the bridge got its name.

He realised it was probably named after a river, yet the land beneath was overrun with grass and vegetation.

“I distinctly remember reading about the Sakarni River in school—it was one of the eight rivers in our district. But I had never actually seen it,” said the 45-year-old, who leads the Paryavaran Sena, an environmental NGO in Pratapgarh.

The mystery propelled him to enquire in nearby villages like Newari, Madhupur, and Sarai Nahar Rai about the Sakarni River. He knocked on many doors, but the response was always the same: “We don’t know.” He realised that both the river and its history existed only in bits and pieces—a puddle here in Varista village, or a priest’s memory of a once-full Sakarni in Newari village were all that remained of the monsoonal river.

“It’s no longer called a river when no water flows. For over two decades, the Sakarni was a river only on paper—for the people, it was either a nala or barren land for cultivation,” said Sehara, the former Pratapgarh CDO.

When Krantikari and other members of the Paryavaran Sena raised the issue of this dead river during a monthly district environment committee meeting, DM Rajan took notice.

For over two decades, the Sakarni was a river only on paper—for the people, it was either a nala or barren land for cultivation

In October 2023, he and Sehara put their heads together to discuss how best to rejuvenate the Sakarni. Initial surveys revealed that silt had accumulated over the past 25 to 30 years. More than 80 percent of the river’s stretch had been overtaken by overgrowth or illegal farmland. While the administration recognised the ecological and cultural significance of restoring the river, they also understood that the task would not be easy.

Restoring the river to its original state would require clearing overgrowth, removing encroaching farmland, and excavating years of silt. This needed substantial funding and labour, resources that were not readily available under the irrigation, water resources, or agriculture departments.

At this point, the administration proposed the precarious idea of using the MGNREGA for this project. A total budget of Rs 1.41 crore was allocated for the river rejuvenation under the Natural Resources Management programme.

“We needed to get the pradhans of 20 villages on board and devise a structure for people to work in sync to restore this river—it seemed impossible,” said Sehara.

MGNREGA, enacted in 2005, guarantees 100 days of employment every year to every household with willing adult members. Previously criticised for low wages, limited scope, and payment delays, the scheme was once described by Prime Minister Narendra Modi as a “living monument to the UPA government’s failures.”

In Pratapgarh district, local residents like Krantikari lament the current state of the scheme. Implemented by the sarpanch of each gram panchayat, it suffers from poor execution and inconsistency across villages.

“Sakarni’s rejuvenation was the first time I saw participation in a MGNREGA scheme on such a large scale in my district,” said Sarita Pandey, leader of a self-help group in Newari village.

Sakarni’s rejuvenation was the first time I saw participation in a MGNREGA scheme on such a large scale in my district

Cultural significance of Sakarni

Sixty-year-old Shiv Kumari from Sarai Nahar Rai village was one of the 30,000 people who worked on the project.

“I saw it neglected for years, to the point where even I forgot it used to be a river,” she said. “But look at how we transformed it. I worked every day from 8 am to 12 pm for two months to clear the riverbed. Now look at the river,” Kumari said, her face beaming with pride. “Koi ise nala nahi keh payega ab (no one can call it a nala anymore).”

The Sakarni is one of the eight rivers of Pratapgarh district, alongside Gomti, Ganga and the Sai, which is famously known for its significance in the Ramayana. Sakarni originates from Khuilan pond in Newari village and flows across 20 villages before joining the Sai River in Banveer Kaach village. According to the 1904 Gazetteer of British India, the Sakarni has “high and often steep banks.”

While not the largest or most important river in the district, the Sakarni holds cultural and religious value for the people of the villages it traverses. It’s tied to the history of the Khuilan Devi Dham temple, which stands at the river’s mouth in Newari village.

A narrow cement road, surrounded by water on both sides, leads to a canopy of large peepal trees that shelter the legendary Khuilan Devi Dham. The deity is a form of Yashoda, Lord Krishna’s mother in Hindu mythology. Every Tuesday, people—especially women—from across Newari come to the temple for the puja and mela held in Khuilan Devi’s honour.

Legend has it that 400 years ago, a priest named Kalika Bhagat lived across the river from the Khuilan Devi temple. In those days, there were no bridges connecting the banks. Through the power of his devotion, Kalika Bhagat would cross the Sakarni River every day to worship at the temple.

Until October of last year, the area around the centuries-old temple was surrounded by fields of jowar, bajra, wheat, and other crops. The Khuilan pond, the origin of the Sakarni, was covered with silt and overgrowth in many places, having lost much of its original surface area. There were a few ponds and wetlands scattered throughout, but nothing indicated that it was the source of a river—except during the monsoons, when the villages would flood.

Legend has it that 400 years ago, a priest named Kalika Bhagat lived across the river from the Khuilan Devi temple. In those days, there were no bridges connecting the banks. Through the power of his devotion, Kalika Bhagat would cross the Sakarni River every day to worship at the temple.

“Every year, I’ve seen my house and fields flooded during the monsoon—sometimes it would ruin our crops completely,” said Roshan Lal Patel, a resident of Newari whose house is right next to the temple. Like Patel, many others had begun cultivating land that originally belonged to the Sakarni’s riverbed, and every monsoon season, their fields would be inundated with rainwater.

This flooding is one reason why convincing local residents to give up their fields and farmlands during the rejuvenation project wasn’t difficult.

“We weren’t asking for the land for any other purpose. It was the river’s land; we were just restoring it to its original owner,” Sehara explained.

Small rivers’ rejuvenation project

Both Sehara and Ranjan credit the 2013 Sasur-Khaderi river rejuvenation project in Fatehpur under IAS officer Kanchan Varma as the inspiration.

This experimental pilot was a huge success, setting a model for other districts in Uttar Pradesh to follow. Fatehpur’s project was lauded for combining local employment generation with river rejuvenation, as well as for its broader environmental impact. In Pratapgarh, the district Jal Nigam chief and the agriculture department chief noted how rivers like the Sakarni contribute immensely to groundwater recharge.

“Over 80 per cent of farmers in Pratapgarh rely on private tubewells for their irrigation needs. If there is one thing that needs to be strong here, it’s our water table,” said Vinod Kumar Yadav, deputy director of the agriculture department.

Sehara also highlighted that one of the main goals of the Sakarni project was to make Pratapgarh water-sufficient. Despite having enough rivers and lakes, the district doesn’t have any dams or barrages, making it entirely dependent on neighbouring districts that control the flow of their rivers through dams.

“My plan with the Sakarni was to take us one step toward self-sufficiency in water. Another goal was to prevent villages and fields from being inundated every monsoon simply because they lie in the river’s path,” explained Sehara, acknowledging that insights from past projects eased the process.

Since the success of the Sasur-Khaderi project in 2013, several other rivers in Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, and Jharkhand have been identified and successfully rejuvenated under similar MGNREGA schemes by state governments. The Odi, Mandakini, Sot, and Tamsa rivers are among those that have been revitalised by their respective district administrations. In Pratapgarh, buoyed by the success of the Sakarni, the DM and Krantikari are now looking to work on the Loni River and Damdama lake next.

Sakarni River in memory

In the main market of Madhopur village, through which the Sakarni traverses, Roshan Lal sat in his paan shop, talking to customers about his crop yield this season.

“This is the first year in my adult life that my fields weren’t flooded during the rains,” he told Arun Yadav, a long-time customer and friend. Just then, two other men walked by and asked about the conversation.

This is the first year in my adult life that my fields weren’t flooded during the rains

“What is Sakarni? Where is it?” asked one of the men, Harish Singh, standing barely 5 km from the river. When Patel and the others explained the Sakarni and the recent rejuvenation project, Singh suddenly snapped his fingers. “Oh yes! That’s the river I read about on Twitter.”

Krantikari and Patel acknowledged that this is typical for many residents of Pratapgarh. While their enthusiasm for participating in the MNREGA project was genuine, Sakarni’s dwindling presence over the past couple of decades has led to its erasure from peoples’ lives and memories.

It is thanks to the stories of Kalika Bhagat, recounted by 70-year-old Laliji Yadav, the current priest of Khuilan Devi Dham, and the memories of people like Sita Kumari that the river has managed to find a foothold in today’s world.

“It was because of their stories and the help of the irrigation department that we were able to trace the original route of the river,” said Krantikari. But word is starting to spread.

Now, when he walks along the main road, people often stop him, recognising him solely for the Sakarni rejuvenation project. Grasping his hand, they thank him for bringing a lost river back to life. This recognition has inspired him to seek out other neglected rivers in the district.

As for the Sakarni itself, the priority now is to ensure it does not get lost again, said Krantikari. He is working with the administration to plant trees and increase greenery along the river’s entire stretch. Fish cultivation has begun in certain sections, and check dams will be constructed soon, along with regular de-silting practices.

“And that is exactly why we need more projects like Sakarni,” added Vinod Yadav.

(Edited by Prashant)