The assault on a 19-year-old BSc student, allegedly by over 10 men, proves yet again that the state is the most unsafe place for women in India.

Rohtak/Mewat/Hisar: Haryana is India’s richest large state by per capita income. It wins the largest number of India’s medals, almost half of all, despite having just about 2 per cent of its population.

Haryana also comes up tops on a score it would rather not: It has the highest number of gang rapes in India. Again, to underline the point, with just 2 per cent of national population.

The sexual assault on a 19-year-old in Rewari earlier this month – allegedly by over 10 men, though only three have been named in the FIR – is just the latest atrocity in a state that saw one gang rape every two days in 2016, according to National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB) data: The number of rapes in the state that year was at 1,187 – an average of more than three a day.

Haryana Police data accessed by ThePrint shows that 70 cases of gang rapes had been registered in the state till 31 May 2018. Of these, 33 are under investigation and 18 are under trial. Last year was no different, with 176 cases of gang rape being registered.

If that is enough to declare an epidemic, then Haryana – the launchpad of the BJP government’s ambitious Beti Bachao Beti Padhao scheme – should have declared one some time ago.

In fact, just a cursory Google search throws up stories of gang-rapes registered from different parts of the state almost every week.

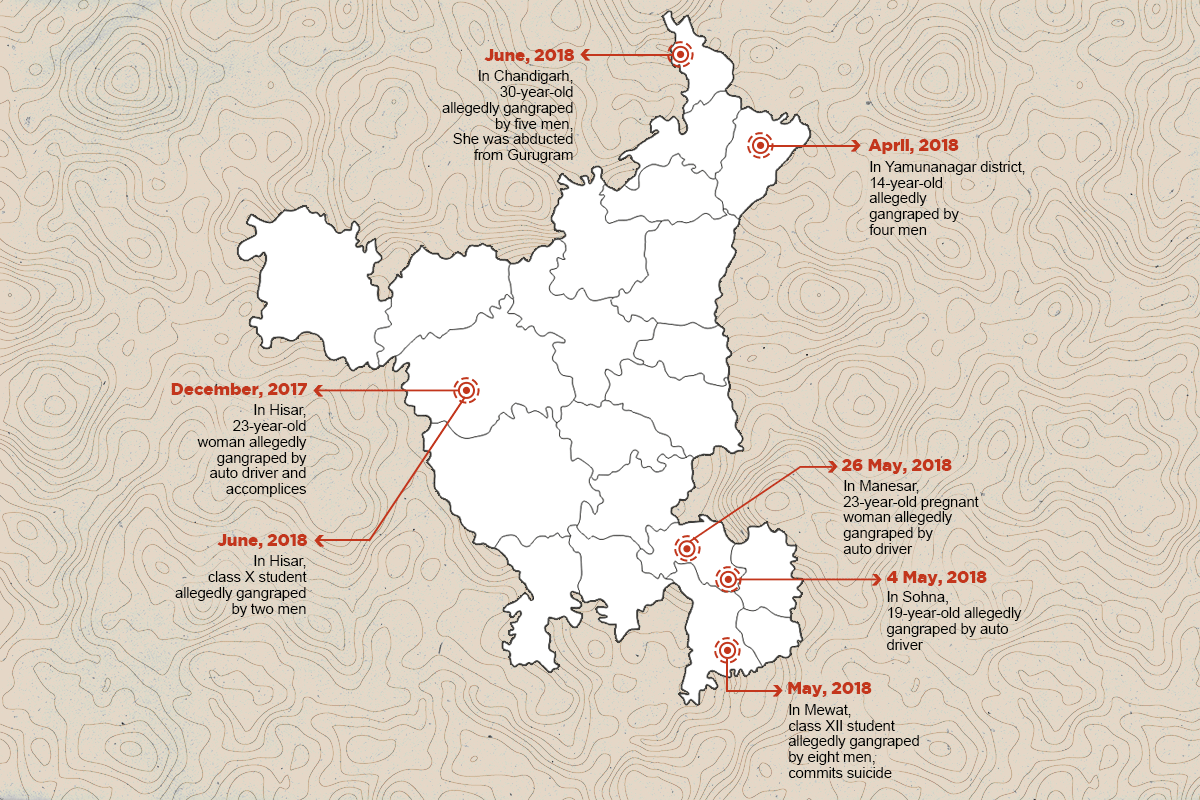

Consider this: In the third week of May, a 30-year old was abducted from a mall in Gurugram by five Haryana residents and brought to the capital where she was allegedly gang-raped by them; barely a week before that, a 23-year-old pregnant woman was allegedly gang-raped in Manesar by an auto driver and his two accomplices; earlier in May, a 19-year old was allegedly gang-raped by an auto-driver and four other men in a deserted locality in Gurugram’s Sohna Road; also in May, a class X Dalit student in Hisar alleged she was gang-raped by two men; in April, a class XII student committed suicide after she was allegedly gang-raped by eight men from her own village in Mewat; again, in April, a 14-year-old was allegedly gang-raped by four men from her village in a dharamshala (pilgrim rest house) in Yamunanagar district.

So, why has Haryana become so dangerous for its women? And what explains this violent abuse of women by men in an otherwise prosperous state?

With some of the worst sex ratios in the country, a deep-rooted system of khap panchayats and innumerable incidents of honour killings, Haryana has never been known for its gender sensitivity or equality. Add to this easy access to pornography, popular culture, co-education in a society that still regards intersex mixing a taboo, unemployment, scores of unmarried men and alcohol abuse, and the problem is an obvious one.

https://theprint.in/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/Gangrapes-in-Haryana1-1024×642-1.jpg

Patriarchy meets popular culture

With more girls venturing out of their homes for education, work, sport, etc., developing friendships with boys and seeking to assert themselves, a new trend of “use and throw” seems to have emerged, says Jagmati Sangwan, state vice-president of the All India Democratic Women’s Association (AIDWA).

“While Haryanvi society remains extremely closed and patriarchal, the exposure to popular culture, social media, smart phones etc. makes women want to befriend boys,” she said.

“There is also desire at a certain age, but since marriages are still largely determined by considerations of caste endogamy, village exogamy, etc. men look at these women as objects of fun, with no intention of marrying them,” she said.

Caste endogamy refers to the practice of marrying within the same caste while village exogamy is the practice of finding a bride or a groom outside one’s own village.

It is important to remember that this exposure is taking place in a society which still has very warped notions of chastity and honour, says advocate Lal Bahadur Khowal who has appeared for several rape victims.

“Parents even in affluent families would change the channel if there is an intimate scene on television,” he adds. “The curiosity only builds then.”

Across villages and districts, smartphones, which provide easy access to pornography, are seen as a huge culprit.

“These days, boys watch whatever they want on their phones, then they go to co-ed schools and see girls, so this is what happens,” says Hakmuddin, a resident of a village in Nuh district — where a 17-year-old committed suicide in April after she was allegedly gang-raped by eight drunk men.

Since relationships with girls, as Sangwan says, are developed only “for fun”, they are objects that can be shared around with friends.

“A lot of cases of gang rape happen when one of the accused is known to the victim, and he then calls his friends to join in the act,” says Rohtak police superintendent Jashandeep Singh Randhawa. “There are also cases in which there was a failed relationship, an extra-marital affair or live-in.”

His argument is corroborated by national data, according to which, in 94 per cent cases of rape of women and children, the accused is known to the victim.

Sangwan agrees. “In a lot of gang rape cases, you see a pattern – the girl knows or is involved with one of the accused, and his friends join in the act,” she says. “This is how a society, which is inherently patriarchal and sexist, shows ambitious or free-wheeling women their position.”

Unemployment + alcohol: A toxic mix

Moreover, in most cases, these men are unemployed, and have no plans for the future, says Sangwan. With nothing to do all day, they gravitate towards alcohol, drug abuse and tend to violently attack girls who they feel are increasingly competing with them in the job market.

“They are not always uneducated…a lot of them are engineers who were promised the moon by private colleges that mushroomed across the state, but didn’t get packages of more than Rs 15,000-18,000,” she says. “Instead of regular employment, you are being given temporary employment, your marriage prospects are low, so this is how you take out your frustration.”

Also read: Men who raped Haryana’s Class X CBSE topper had ‘assaulted’ other women in the past

Although Haryana is among one of India’s well-off states, its unemployment rate is among the highest in the country at 15.3 per cent, according to Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy (CMIE) data.

In Mewat’s Nuh, for example, where the 17-year old was allegedly gang raped, unemployment among young boys is rampant, say villagers. The district, which is only two hours away from the national capital, lies at the bottom of Niti Aayog’s most backward districts in the country.

“None of the men (accused) are educated or employed,” said the victim’s father. “They are the dabang of the village…they have a lot of money and can buy anyone they wish…they drink all day, but nobody can dare say anything to them.”

Across the district, one can see groups of young men huddled on charpoys outside shops and homes gambling or just playing cards even in the morning.

“Eighty per cent of the boys in this village are into gambling,” says a 45-year-old man who has sent two of his daughters to study in a madrassa in Gujarat. “They are safer there than here.”

Alcohol — cheaply available at every nook and corner and consumed almost only by men — adds to the problems.

“A village might not have a medical shop, but every village has a theka (liquor vend),” says Paro Mishra, an assistant professor of sociology at Banasthali University in Rajasthan’s Tonk district, who has done extensive fieldwork in Haryana. “Even as a researcher, I was advised to not go to certain areas because they would have drunk men loitering around.”

Police officers who ThePrint spoke to also mention the increasing menace of drug abuse across the state. “You will see massive drug abuse by men, especially younger ones or those who cross the marriageable age and don’t get married,” says Rohtak SP Randhawa.

According to reports, the number of addicts who visited the State Drug Dependence Treatment Centre in Rohtak for treatment shot up to 3,707 in 2016 from 774 in 2010.

No brides for Haryana’s men

The state’s skewed sex ratio, which has given rise to its peculiar problem of the “missing brides” and chade, or over-aged bachelors, is a major factor in the growing instances of sexual mob violence against women, says Mishra.

According to the 2011 census data, Haryana’s child sex ratio at birth was 834 girls per 1,000 boys and the overall sex ratio was 879 – giving rise to a massive bride crunch in the state.

“In Haryana, the marriage market has been heavily imbalanced…especially at the bottom of the hierarchy, there are surplus men. If a man is unemployed and landless, he is finding it increasingly difficult to find a bride,” she says.

Also read: Kidnappings double, rape cases up as Haryana sees sharp rise in crimes against women

With no other means to satisfy their sexual energy, says Mishra, they take to rapes and gang rapes of young women, because it is ultimately a society that toxically conditions men to think women owe everything to them.

“During my fieldwork, a lot of times such men were referred to by villagers as chhutta saand (untamed bulls), who will molest any woman they see,” she says.

The state government has, at least on paper, made several attempts to make the state safer for girls. Haryana was the launchpad of the central government’s ambitious Beti Bachao Beti Padhao scheme; it also started ‘Operation Durga’ in 2015, its own version of Uttar Pradesh’s anti-Romeo squads, and opened women’s police stations in every district.

The caste-khap connect

However, in a state where there is a solid nexus between politicians and khap panchayats, any real change remains elusive, said advocate Khowal.

“I have been involved in cases where girls have turned hostile because of khap pressure or the police has withdrawn cases against the accused because of them,” he says.

A 27-year-old Dalit woman, who was gang raped by three men in a moving auto in December last year, for example, did not know any of the accused. Yet, while raping her, one of the accused — an upper-caste boy — allegedly said to his accomplices, “Valmikiyon ki ladki hai,aaj haath aayi hai, chhodenge nahi (She is the daughter of Dalits, we’ve managed to catch hold of her now, we won’t leave her).”

“They have their own systems of doing a recce…they figure out because they know they have the blessings of the khaps,” says Khowal.

Worse still, in a state that should be dealing with crimes against women with alarming urgency, the police claim to approach gender crimes with “a pinch of salt”.

Police attitude

Haryana’s top cop, DGP B.S. Sandhu, who blames the rise in gang rapes on the “erosion of social values”, like many of his officers across the state, also expresses some doubt about the veracity of these cases.

“Thirty per cent of rape cases are false, the cancellation rate (of gender crimes) is very high…There are gangs that are working to extort money (in the name of rape cases),” he says.

In 2018, of the 70 cases that were registered until 31 May, 19 have already been cancelled. In 2016 and 2017, as many as 120 cases were cancelled.

Contrast this with the conviction rates. For the cases registered in 2016, only nine saw convictions, while there were 48 acquittals. For 2017, there have been only two convictions and 16 acquittals.

ADGP law and order Haryana A.S. Chawla, who is also the in-charge of the cell for prevention of crime against women, says the conviction rate in case of rapes and gang rapes needs to be improved.

“Investigating teams have been clearly instructed that they should focus on gathering scientific evidence in such cases so that even if the victim backs out of her complaint/statements, conviction of the accused is ensured,” Chawla told ThePrint.

Also read: It’s 2018, and Haryana is still swapping the girl child for marriage

Forensic labs have also been issued instructions that reports on evidence gathered in rape cases have to be dealt with on priority and expedited.

“Investigation in gang rape cases has to be complete within one month of lodging of FIR,” he adds. Yet, investigations of 11 cases registered in 2017 are still under investigation.

“The data for 2018 shows that till May 31 four districts in the state have not had any case of a gang rape. These include Panchkula, Yamunanagar, Charkhi Dadri and Palwal. Gurgaon has been generally reporting the highest number of gang rape cases followed by Mewat. In Mewat, however, we have seen a trend emerge that the number of false complaints is also substantial,” says Chawla.

According to police data, 35 and 47 cases of gang rape have been registered in Gurgaon and Mewat respectively in the last three years.

Difficult road ahead

While the state is expected to launch a state action plan to address gender crimes soon, for a society that refuses to leave behind archaic ideas of sexual propriety, gender equality will remain an alien notion.

“Parents don’t want to have the necessary conversations about sex, rape, consent, etc. It’s all alien to them…So boys have half-baked knowledge about everything,” said Khowal.

With inputs from Chitleen Sethi in Chandigarh.

This article was originally published on 25 June.