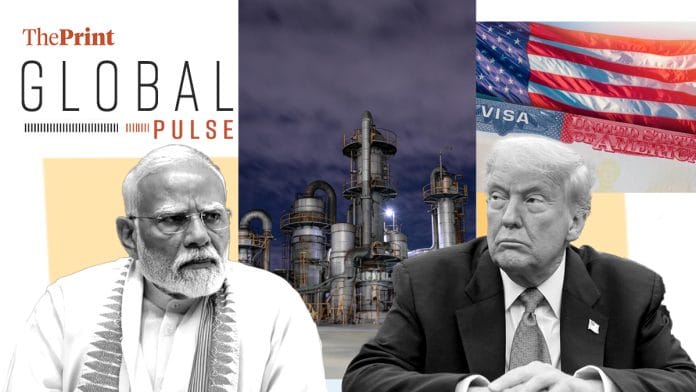

New Delhi: India’s “spree” of buying discounted Russian crude is set to come to an unceremonious end, right before US President Donald Trump’s sanctions on companies doing business with Russia’s two oil firms kick in, reports Alex Travelli in The New York Times.

“India’s intake of Russian crude became a stumbling block in its ongoing trade negotiations with President Trump, who started telling the country to stop buying it over the summer. In August, he stunned India by imposing a special tariff to punish it for buying the oil, effectively doubling the US import duty on Indian goods to 50 percent, which dealt a crippling blow to a range of industries,” says the report.

Travelli notes that India halting Russian crude imports would signal a win for Trump, and India would not appear to have been “directly coerced”.

Energy companies are also having to make swift upturns in order to adhere to the ban.

“Although India’s oil refiners are hustling to load up on Russian crude before the deadline, they are expected to obey the new rules to avoid the penalties that the US Treasury could inflict on them and their partners, which include international banks and technology firms,” the report says.

“A spokesman for Reliance Industries, India’s biggest private oil company, said the company had ‘an impeccable record’ of adhering to sanctions and would abide by the new rules,” it adds.

At the outset, the tightening of visa regulations the world-over, particularly in the US, was seen as detrimental to India. But a piece in The Economist has a different take.

“Cutting mobility will affect India in three main ways. The first is a loss of remittances. Cash from emigrants is worth around 3% of Indian GDP, covering about 40% of its trade deficit. Rich countries became the dominant source for the first time in 2024, according to the central bank, overtaking the Gulf countries where migrants, many of them low-skilled, send large chunks of their pay-cheques back to their family.”

“Those working in America are typically the best paid. A software developer in San Francisco can earn many times more than someone with similar skills in Bangalore, Hyderabad or even Dubai,” says the report.

In Financial Times’ India Business Briefing, Andres Schipani compares the long-pending India-US trade deal to Samuel Beckett’s play Waiting for Godot.

“Over the past week, the US has announced trade deals with Argentina, Ecuador, Guatemala, El Salvador and Switzerland. What happened to India, whose prime minister is avowedly a “great friend” of Donald Trump? For almost two weeks now we have been hearing, both in New Delhi and Washington, that the much-vaunted India-US trade agreement is almost done,” he writes.

“Is it? I often feel I am in Samuel Beckett’s play when it comes to this deal.”

The newsletter also looks at the shares of Tata Motors Passenger Vehicles, which dropped by more than 7 percent over concerns about its Jaguar Land Rover subsidiary.

“As JLR accounts for a lion’s share of profits for Tata Motors Passenger Vehicles, worries about its growth crashed the parent’s share price to Rs 363 soon after markets opened on Monday, taking it to a seven-month low. Though slightly better since, its shares are still in the doldrums—at the absolute bottom—of India’s blue-chip benchmark Nifty50 index,” writes Schipani.

Also in Financial Times, Andres Schipani and Jyotsna Singh report on a herculean project—India’s bid to create a skilled workforce.

“With Prime Minister Narendra Modi focused on boosting Swadeshi—locally made products—as punitive US tariffs squeeze export industries and threaten to put a damper on the world’s fastest-growing large economy, the opportunities for India’s workforce of more than 600mn have rarely been greater,” says the report.

“Yet government officials and leaders in industries from services to manufacturing to energy lament a critical shortfall of practical training, digital literacy and soft skills.”

According to the Indian finance ministry, only 4.4 percent of India’s workforce between the ages of 15 and 29 is formally skilled.

“India’s skilling infrastructure has always been very, very small,” Pronab Sen, an economist and former principal economic adviser to India’s Planning Commission, is quoted as saying.

He adds that as the economy expands and grows more sophisticated, “we need to meet the demands of the organised sector, the big companies”.

And even when it comes to skilling, there are a slew of challenges—including India’s rising population.

“The growing population could also put further pressure on fast-skilling the workforce. For Sourav Roy, chief of corporate social responsibility at Tata Steel, ‘there are more people that need skills than what we can actually offer in general’ in India,” the report says.

(Edited by Nida Fatima Siddiqui)

Also Read: Adani DoJ probe at ‘standstill’ while Trump reshapes ties with India & Reliance’s retail ambitions