India is being a killjoy neighbour—according to a strongly worded editorial in Pakistan’s Dawn.

The editorial declares that never before has India stopped “practically all good-neighbourly activities” like it has under the current regime. Trade relations continued as bilateral relations soured. Even during the Kargil War, as troops were locked in exchanging fire, the Indian public got to enjoy the Pakistani mango.

But today, the Modi government has “clamped down on people-to-people contact in a notably damaging measure against the seekers of peace and fellowship on both sides.” Trade across the line-of-control, it continues, was shut down with “a perverse intent to harm the Kashmiris.” And yet, officially sanctioned trade continued—though massively diminished. So why the loss of friendly neighbourly spirit?

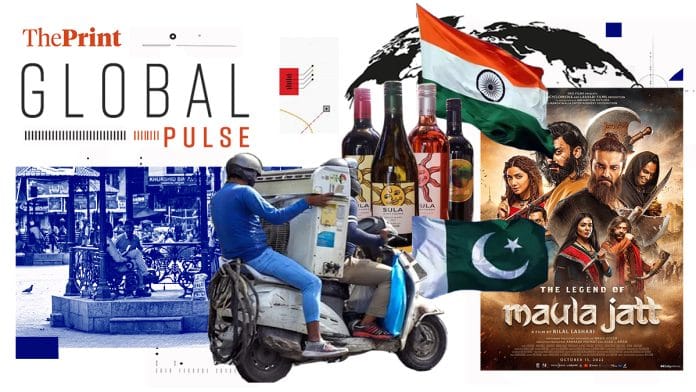

The real bone to pick seems to be the release of Pakistan’s 2022 blockbuster, The Legend of Maula Jatt. It was due to release in Punjab on 2 October, “possibly to coincide with the birthday of Mahatma Gandhi, an inveterate advocate of friendship between the two countries,” the editorial says. But “right-wing Hindu groups” blocked the release—and the editorial implores these groups to reason with themselves.

“How is importing Pakistani chemicals alright and watching a Pakistani movie anti-national?” it asks. “Or, as the late Pakistani writer and public intellectual Intezar Husain would remind his leaders, how was it right to import potatoes from India but keep Lata Mangeshkar at bay?”

Rabid elements “on both sides” are intent on sticking to bitter pasts, the editorial finishes. They “seem to feel threatened by the simple joy of going to a movie together.”

The editorial was published just as Jammu and Kashmir finished voting in its first regional election in a decade. It’s an election that global media has been watching, and the Financial Times tell us why: the way the cookie crumbles offers “signs of the future direction of one of Asia’s most intractable conflicts.”

In a report on the elections, the FT notes how Kashmir is a “perennial flashpoint between the nuclear-armed neighbours”. A peaceful election is a PR coup for the BJP, which says it brought peace to the state. Paramilitaries in security vehicles closely monitored voting to ensure order.

“Bringing Kashmir under the same regime as India’s other states has long been a pet project for the BJP,” the FT reports, mentioning how the rapid and “intense development” of road and other public infrastructure has transformed the scenic mountains into a massive construction site, leaving Kashmiris with high electricity tariffs, drinking water shortages, and high unemployment. Drugs are also on the rise.

And exit polls, the FT reminds us, are not always accurate—just look at June’s general election exit polls. Whatever the result, the elections in Kashmir are certainly a test of the BJP’s local popularity, independent of what the rest of India feels about the state.

“Analysts said lasting peace and stability for Jammu and Kashmir would require more than democratic elections,” the FT concludes. The state can’t be thought of in isolation, certainly with Pakistan in the picture.

Other foreign publications are no doubt holding their breath for the election results to be declared Tuesday.

In the meantime, the Washington Post turns its attention to the rise of air conditioners. So far, ACs have mostly been concentrated in the West—but as temperatures rise, those in parts of the world most in need of cooling down are eagerly acquiring ACs, for the first time. And India, which is expected to add hundreds of millions of new AC units over the next few decades, offers an ideal site to understand this phenomenon.

The story begins in Thane, in the household of a 60-year-old, training the vents of an old window towards his face. Before they could buy it, his family would fill a bucket with ice water and then tip it over the floors to stay cool, lying down on the bare surface to sleep.

Only about 5 percent of India’s 300 million households had ACs in 2018. But last year, around 8-10 million AC units were bought, and for about 90 percent of the buyers, it was their first purchase.

The story meanders into the global AC story, looking at how they work and the technological updates they’ve received to overcome environmental challenges. What it adds up to is this: For poor Indian families, it makes more financial sense to invest in efficient ACs that are environmentally friendlier and won’t rack up such high electricity costs. But getting there is tough until people understand the potential cost difference and energy savings.

Global media’s gaze is vast. It examines both the poor and the rich in equal measure. In the slums of Thane, the AC is a godsend. In posh hotel rooms, however, it becomes a reason for shivering wealthy Indians to order, swish, swirl and sip glasses of full-bodied red wines—to warm themselves up.

After describing cheese culture in India last week, global media has now turned to some other classic liberal elite fare: wine. The FT samples a range of nine wines for this piece at a dinner organised by India’s “one and only Master of Wine, Sonal Holland”. The South Asia Bureau Chief John Reed notes that Indian wines here have greatly improved since 2017.

“Per capita consumption of wine may have risen in recent years, but it’s still not much more than two centilitres a year,” the story says. High import taxes means that 75 percent of the wine sold in India is Indian—and Sula Vineyards makes up about 60 percent of that number.

“But the really well-heeled drink imported wine,” the FT admits. “The Indian sommeliers I met were unanimous that more somms are needed in their country, pointing out that there are probably a thousand bartenders for every wine waiter.”

The top hospitality schools also struggle to mould sommeliers for the future, since they’re often forbidden from serving alcohol, as virtually all their students are under the age of 25.

Still, the change is rapid. Indian wines are very much on the rise, FT tell us. Fifteen years ago, the current situation would have been “unthinkable.”

“This is one rapidly growing market that gives the world’s wine producers, concerned about shrinking sales elsewhere, some reason to be hopeful,” it concludes.

(Edited by Zinnia Ray Chaudhuri)

Also read: Global media on Indians working longer than Japanese & Vinesh Phogat’s political bout

Yeah, Bharat is a killjoy neighbour for calling a spade (jihadism) a spade.

As for the film, we all know that Lollywood is more often than not just subliminal propaganda directed against us (Dharmics and Bharatiyas). It isn’t for no reason that some films and series are made to target Pakistani *and Indian* Muslim audiences – it’s covert messaging (case in point: Sevak, Dastaan).

What does India gain by normalising ties with Pakistan? How does it benefit India?

Irrespective of India’s stance vis-a-vis Pakistan, it will continue to be a hub of Jihadi organizations. It is the global capital of Islamic fundamentalism and fanaticism and will always be a headache for the world.

India is unfortunate in that it is an immediate neighbour of Pakistan.