When Amish Tripathi’s The Immortals of Meluha, the first in the Shiva trilogy, was published in 2010 to massive fame after being rejected by 40 publishers, he made two bold observations: He had proved publishers wrong who thought mythology would fail, and Indian publishing was set for a big change through translation and pride in culture. “I have enough stories to keep myself busy for the next few decades!” Tripathi had claimed then.

But Tripathi has been proven right on only one count. In 2022, India is loving good translation works. But its fiction sales are seeing some handwringing. Enter a bookstore and you see the likes of cult bestselling authors – Devdutt Patnaik Amitav Ghosh, Amish Tripathi, Ashwin Sanghi. It isn’t a long list. But it’s the non-fiction shelves that are teeming, vibrant, and alive. There’s new energy and enthusiasm among readers and publishers for fact, data, narrative, theory, and experiences. Fiction’s time under the Indian sun might just be over.

“Fiction is in a dismal state,” says Kanishka Gupta of Writer’s Side, the literary agent representing Daisy Rockwell, the translator of Geetanjali Shree’s Tomb of Sand. “Publishing houses are cutting it down, and there’s little machinery to support its growth.”

“Non-fiction is king,” The Hindu had declared in July.

Also read: Mini JLFs sprouting across India. Lit fest boom in Nagpur, Ranchi, Kanpur, Indore, Kokrajhar

Can literary prizes help fiction?

Literary prizes are a major factor that determines the growth of the publishing industry, and winning does feel good. It would now appear that International Booker-winner Tomb of Sand was a work of fiction waiting to burst out into Indian collective consciousness.

Geetanjali Shree’s novel, Gupta says, was an “unexpected surprise”. It wasn’t even selling 1,000 copies before it shot to international fame with the International Booker Prize. Now, Geetanjali Shree is a darling of the Indian literary world who took Hindi fiction from the heartland to English homes. But does Avni Doshi’s Girl in White Cotton ring a bell? The book was shortlisted for the Prize in 2020 and released as Burnt Sugar in the UK. Today, it can barely squeeze in any space on Indians’ bookshelves or their memory.

India’s literary prizes, besides making humble entries in newspapers every season, are doing little to encourage fiction on a large scale. Gupta also mentions that half of the awards have been “insidiously, silently shut down,” and the remaining have only enough gas to keep running the show. Madhuri Vijay’s The Far Field or S. Hareesh’s Moustache, the winners of the prestigious JCB Prize in 2019 and 2020 respectively, called ‘India’s most valuable literature award’, are resting in bookstore attics unsold. With the Sahitya Akademi’s “silent march into oblivion,” and little enthusiasm for the Hindu Literary Prize in a digital age — perhaps, literary awards are now a 20th-century relic — Arundhati Roy’s 1997 Man Booker Prize was possibly the last that instantly catapulted her into sensational name and fame in Indian literature.

Has Geetanjali Shree chalked up a similar legacy? Not many takers for that argument, sadly.

Also read: Uttar Pradesh had a thriving literary culture in the 1980s, but proximity to Delhi killed it

Non-fiction rules publishing industry

So, who’s calling the shots in Indian publishing now?

The share of non-fiction has gone up 58 per cent in the last few years, according to data provided by Penguin Random House India. “There’s been a big increase in non-fiction sales. We’re seeing more demand for categories like self-help books and sports. More importantly, while these readers aren’t converting to fiction reading, more fiction readers are taking up non-fiction,” says Nandan Jha, EVP business development and product and sales. Non-fiction also saw a 21 per cent increase by volume, Neilson Book Scan data shows.

“There was always an ‘intimate’ reading battle between fiction and non-fiction readers. Fiction isn’t everyone’s cup of tea, but more non-fiction has picked up over the last few years,” says Aman Arora, senior marketing executive at HarperCollins.

Biographies, history, political theory, geopolitics, self-help, health and spirituality books are beating the odds over the last decade. “Readers are now looking for ‘serious’ authors and credible writers, or ‘utility products’ that can add value to life. Books by ‘gurus’ are doing extremely well too,” says Arora.

Spirituality, self-help and ‘indigenous science’ are storming the charts. Pedestrian booksellers run around traffic lights selling Think Like A Monk by Jay Shetty, a former Hindu monk. A smiling Gaur Gopal Das, with a Vaishnavite tilak on his forehead, on the cover of Life’s Amazing Secrets, is a common sight. Sadhguru became sensational in the US after Inner Engineering: A Yogi’s Guide to Joy became a 2016 New York Times bestseller. Sold-out crowds of thousands thronged bookstores in over 17 cities in the US; Will Smith tweeted enthusiastically about it. Now, Sadhguru is a regular during Smith’s dinner-table banter with his daughter.

A reason behind the rise of Indian gurus in books could be the West’s obsession with them, but there’s undoubtedly larger machinery at work. It comes at a time when the Ministry of Ayurveda, Yoga and Naturopathy, Unani, Siddha and Homeopathy (AYUSH) is getting its foot in the door. The ministry launched four publications last year — to “propagate Indian systems of medicine” and heritage, both locally and globally. Moreover, there’s a push for more Indian history reading too. And the Ministry of Culture is ‘in’ on it — this year, the Narendra Modi government posted a wide-ranging reading list of India’s ‘unsung heroes’ on the culture ministry website.

The undiscovered ‘basement history’ is now a favourite genre of elite bookshops.

The sales for Josy Joseph’s A Silent Coup, Christophe Jaffrelot’s Modi’s India, and Nalin Mehta’s The New BJP are ballooning. When it isn’t a savoury read on politics or history, readers are satisfying a ‘data diet’ — look at Rukmini S.’s Whole Numbers and Half Truths. And when they aren’t in the mood for hard reading either, Shrayana Bhattacharya’s Desperately Seeking Shah Rukh makes for an engaging but researched read.

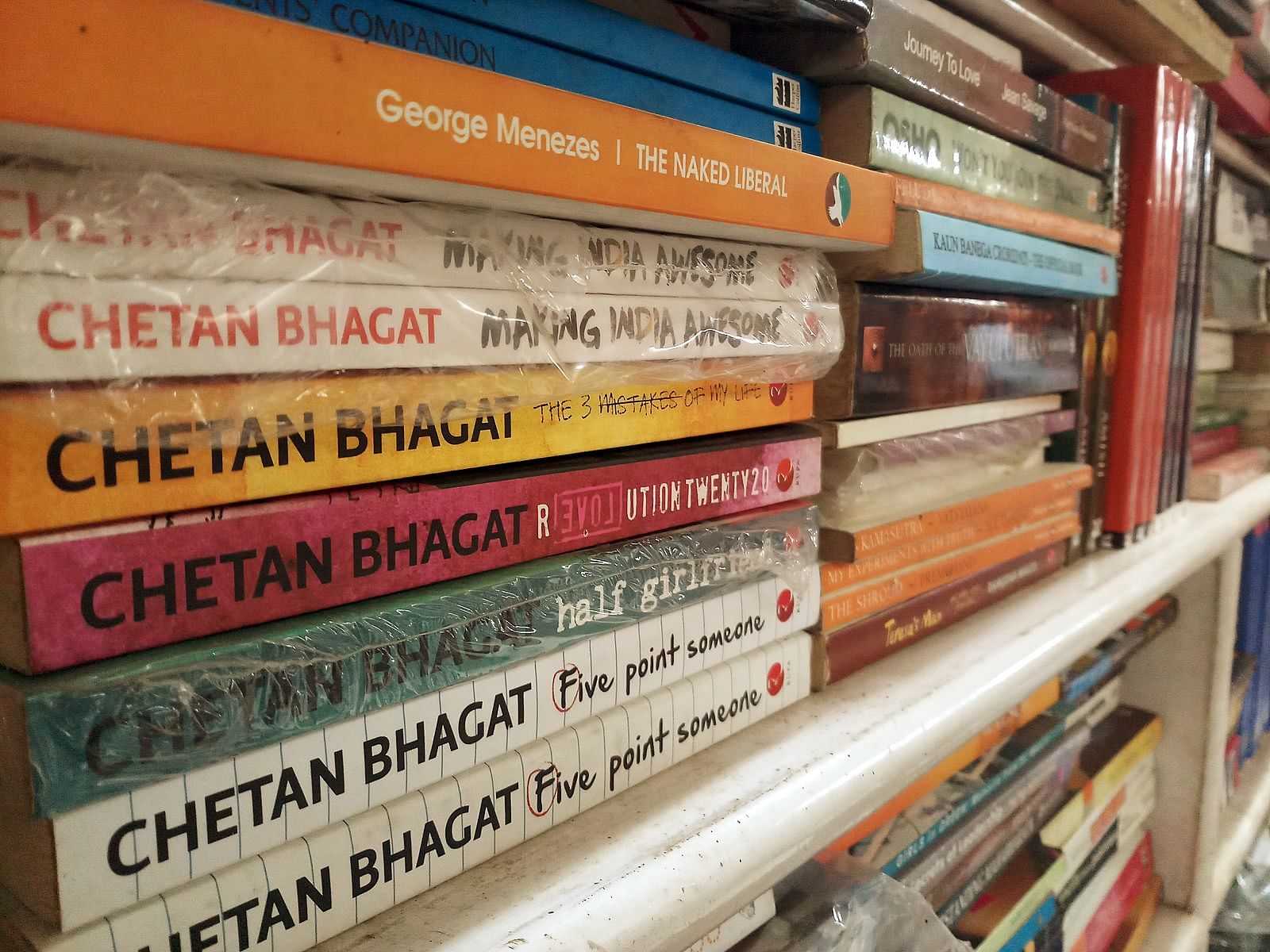

In India, non-fiction has picked up precisely due to the buoyancy that good marketing provides it. Novelists such as Ravindra Singh, Durjoy Dutta, and Chetan Bhagat aren’t actually as popular anymore, according to Himanjali Sankar from Simon & Schuster. “From crime to romance, sales are low, and non-fiction sells a lot more, especially narrative non-fiction. It is moving, it’s the future,” she said.

As gatekeepers, publishers have a restrictive wish list for fiction writers. They give the keys to the kingdom to those with the big fat names: Editors, journalists, actors, celebrities, and social media influencers. For instance, BJP minister Smriti Irani’s latest novel Lal Salaam. Bollywood celebrities and TedTalkers are trendy, fashionable, and perfect to post on social media handles with a cup of tea. As influencers, they do most of the promotion of their books, and publishers don’t have to spend their resources. Publishers say author profiles matter when they’re combing through the thousands of pitches that land on their desks.

The problem is that ‘discoverability’ gets affected. And there are very few first-time novelists surprising us now.

“It’s a great game of Kaun Banega Crorepatis — hundreds come every week, month, year. The question we need to ask is: While there’s a lot of potential out there, are publishers willing to take the risk?” asks Sanjoy K. Roy, managing director at Teamwork Arts at the Jaipur Literary Festival. He also adds that more than half the publishing industry has a greater appetite for non-fiction.

Also read: Babri, Saraswati, Aryans – There are rival Indian histories now and campuses are the warzone

Rise and fall of the Chetan Bhagat moment

Today, it’s not myths, stories, and fiction that are conversation starters but ‘serious’ ideas popular in mainstream culture — national politics, economy, mental health, Covid, geopolitics. That explains the publishers’ search for ‘serious, deep journalism’ that can stay the course in the country.

Non-fiction is adding a perceived notion of intellectualism to dinner tables. “Today, people want to read non-fiction because they think, ‘I should be talking intellectually’,” says Karthika V.K. of Westland Publications. This phenomenon of social ‘show-offism’ is the malady that has hurt fiction. Everybody is arguing about their idea of India today – at dinner tables, parties, social media, literature fests. Non-fiction gives them the fodder for this head-butt over ideas.

Some of Westland’s most prolific titles dared to look straight into the bull’s eye of Indian politics – India’s Undeclared Emergency by Arvind Narrain, Price of the Modi Years by Aakar Patel, and Despite the State by M. Rajshekar. Its shutdown in February this year was the cause for much insider speculation: Popular narrative says that luring Chetan Bhagat and Anuja Chauhan into its fold and having faith in their writings as well as Amish Tripathi’s was a mistake — readers’ taste is shifting to non-fiction. New-age readers are consuming Netflix and YouTube and are not poring over pages and pages of fiction.

The best decade for fiction was the 2000s, says Advaita Kala, who rose in the late 2000s with her debut novel Almost Single. Amish Tripathi, Chetan Bhagat, Jhumpa Lahiri, Durjoy Dutta — all are products of that time. There was a “buoyant” space for commercial writers — Chetan Bhagat, a writer previously treated “very shabbily” was catapulted into a commercial cult with the release of Five Point Someone in 2004, which sold over a lakh copies in no time of its launch.

That was the high for Indian fiction. Now it’s mostly for literature aficionados and college students.

No book club in India has the kind of clout that Western ones do and review columns are shrinking — Hindustan Times’ is now a single page, and NDTV’s Just Books has faded into the background since the early 2010s. The list of invited speakers at literary festivals isn’t too impressive either, says Kala.

“The joy of a story told well isn’t enough. And that’s tragic. Have we passed that moment of the ‘Big Indian Book’? We’re still waiting for the next Vikram Seth,” she adds.

Will Netflix buy my book?

There’s some spite among writers seeing the success of OTT content in India. A lot of fiction writing has changed its medium — from paper to celluloid. Kala mentions how a lot of books are written in the hope of turning them into web series. Many say that India’s fiction readers have moved to OTT-watching.

Vikram Chandra’s Sacred Games was caught in a tug of war between publishing stalwarts across the UK, US, and India: HarperCollins, Faber & Faber, and Penguin all bought publishing rights at six-figure deals.

The book failed to draw much readership.

Chandra waited until 2018 when Netflix’s adaptation became a global success.

“I don’t understand it when people say, ‘I don’t read fiction’,” says a disgruntled Rupleena Bose, a PhD scholar at Sri Venkateswara College, Delhi. “What they don’t realise is that so many serialised novels are now streaming as their favourite shows on TV.” The love for fiction is still there, but the moment TV screens go dark, Indians are hunting for “educational content” that can “add value to their lives”.

And that’s the sentiment Rupleena felt when she approached her publisher who showed little interest in her novel but in the opening conversation itself dug into the details of her PhD thesis on urban music from ’90s Bengal.

Also read: Savarkar broke monopoly of Nehru-Gandhi history books. Now there’s new appetite, wishlist

Hindi and Urdu wallflowers

Is it just the English readers who have felt “they should be talking intellectually”? The uptick in non-fiction is being seen in Hindi publishing as well.

In Hindi publishing, the yesteryear legacies of Rabindranath Tagore, Premchand, and Narendra Kohli haven’t found much of a replacement today. Prabhat Kumar from Prabhat Prakashan says that teenage fiction, which was doing well a decade ago, is seeing a significant drop today. In 2003, J.K. Rowling’s Harry Potter series in Hindi was booked two weeks in advance — all 40,000 copies. That too from small towns and villages, where Maglus (muggles), paras patthar (sorcerer’s stone) and adarsha chadar (invisibility cloak) became buzzwords.

Kumar also says that the “Western validation” accorded to Geetanjali Shree is a “dangerous trend”. For four years, Tomb of Sand had been lying flat. Except for Chandrakanta Santati by Devaki Nandan Khatri, when non-Hindi speakers went out of their way to learn the language just so they could read it — there’s little that the industry could boast of. He also laments the vacuum in the heartland that blows the trumpet of Hindi supremacy: “North Indians would rather spend hundreds on ice creams at India Gate. If they bought Hindi books instead, imagine where we’d reach.”

And Urdu is the saddest wallflower in the big picture.

“There are very few writers in Urdu non-fiction, partly because we have no experts in deep journalism, economics, politics. And on a national level, Urdu is a declining language too. There’s a whole nexus of support for languages like Marathi with various newspapers, websites, and news channels that encourage socio-political engagement. Most Urdu newspapers have biased judgement with little objectivity. It’s Urdu’s badnaseebi (tragic fate),” says Rahman Abbas, the recipient of the 2018 Sahitya Akademi Award for his novel Rohzin.

But the biggest irony is this. In this race for ideas, narratives and faux-intellectualism, all non-fiction books in India are really competing for sales with one biggest and long-standing bestseller —the Manorama Yearbook.

This article is part of ThePrint’s series on current trends in the book publishing industry. Read the series here.

(Edited by Neera Majumdar)