The letter engineers wrote to ISRO scientists about the India-made engine that powered the country’s first rocket ship, the private papers of the man who heralded India’s Green Revolution, and the photograph of MK Gandhi visiting an indigenous drugs manufacturing company in 1939 with his private doctor—these snatches of history from India’s early nation-building years are not preserved in any government archives.

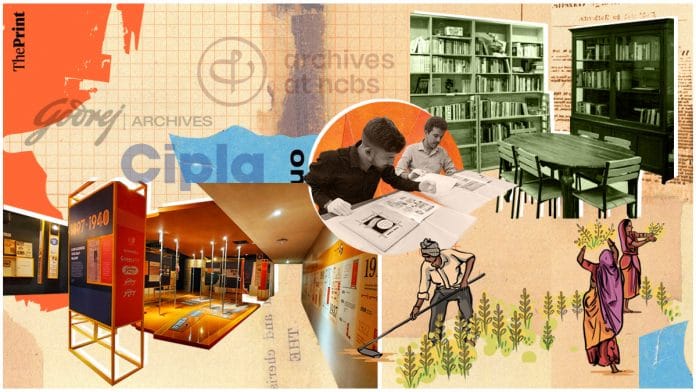

But a parallel universe of archives is rising in India that is collecting stories of modern India in private corporate offices and public institutions. And these archives are dotted across the country, tied to the institutions and corporate entities that helped bring them into existence.

It would not be possible to write a comprehensive history of the Green Revolution without the papers of MS Swaminathan, held by the National Centre for Biological Sciences (NCBS), a public institution in Bengaluru that receives funding from non-governmental and government sources. Nor would it be possible to tell the story of India’s space expeditions without the help of the archive at Godrej, which manufactured the Vikas rocket engine for the space agency.

Corporations such as Tata, Godrej, Cipla, Wipro and public collecting centres like the Archives at NCBS have begun setting up their own archives and are now playing an integral role in public history.

“Earlier, those who work at the company may have thought about history-making many assumptions — that the history of Godrej that we are trying to preserve might be about family records or it’s a top management initiative,” said Vrunda Pathare, Head of the Godrej Archives. “They never thought that even an engineer’s diary would be useful for us!”

Also read: ‘This is a tornado’—Hindu American Foundation wants people to care about Hinduphobia

Show, don’t tell

Corporations are often seen as fortresses that are difficult to pry open, closely guarding their information and working processes.

But companies such as Godrej, Tata, and Cipla have opened their doors to archivists and audiences alike — Tata being the first at the turn of the century. Some use the archive to supplement their corporate communications and marketing strategies, while others bring out publications and hold public exhibitions.

The key to convincing corporations to do this, according to archivists, is to show — not tell.

“Even if it is a corporation, at the end of the day it’s the people’s story and the role they played in building modern India,” said Sanghamitra Chatterjee, archivist and founder of heritage management company Past Perfect. “If there’s no custodian, all this material gets lost again.”

And besides historians, archivists, and students, people are waking up to the magic of people’s history. Employees are not only aware that their actions contribute to the larger picture, but are also taking greater pride in their work because they know it’s going to be documented in some way, however small.

According to Cipla’s spokesperson, passion and pride in the company’s legacy drive even former and retired employees to share memorabilia from their time with Cipla.

“Pride in the company’s rich legacy is driven from the founders (promoter family) to the leadership and down to every Ciplaite. Everyone is passionate about the cause,” said the spokesperson.

Also read: Assam State Archives shows how it’s done—5 lakh documents, 6000 maps, digitisation drive

Telling the story of India’s growth

Private corporations are now inextricably linked to the story of India’s industrial growth, tracing the trajectory of a newly independent country trying to be self-sufficient.

“Cipla founder Dr KA Hamied was an Indian nationalist and ardent follower of Mahatma Gandhi. As a result, ideals of self-reliance, and self-sufficiency led him to start Cipla as an indigenous pharma company,” wrote a Cipla spokesperson to ThePrint.

A 1948 advertisement from Cipla sums up the aspirations of a nascent India: “Swadesh, India’s freedom is what every citizen demands! Be Indian minded! Use Cipla’s medicines! Made in India = world’s best,” declares the bright red flyer.

Cipla’s archive, set up in 2014, has collections spanning over 87 years of the company’s history, which include books, documents, photographs, marketing literature, and oral histories.

It shows how the company exported essential medicines to Rangoon, Myanmar during the second world war. It also documents how MK Gandhi’s visit to the Cipla factory in Mumbai in 1939 accompanied by Sushila Nayar, his personal physician— who would go on to become independent India’s second health minister — only strengthened Dr Hamied’s resolve to make India self-sufficient in drug manufacturing. The archive also tracks how Cipla and other like-minded pharma companies in India urged the government to amend legislation like the Patents and Designs Act of 1911, leading to the newly amended law in 1970.

“The archive’s collection holds material to several incidents like these that affected the Indian pharma trajectory,” said Cipla.

Similarly, the Godrej family had also started collating and collecting things for their archive, the seeds of which were sown when the company celebrated its centenary in 1997.

The Godrej Archives were formally set up in 2006 at Godrej & Boyce with Pathare joining as an archivist. Anything and everything is useful for Pathare and her team — from emails to marketing numbers to photographs of events. Godrej Archives is, since then, baked into HR induction process of the company. Every new recruit first experiences the history of the organization through a presentation and interaction, and also understands how they can help contribute to it.

The team started putting together the Archive after understanding the entire company structure first. They chose the company’s youngest business unit as a template for archiving: Godrej Aerospace, which at the time was 30 years old. It was bound to have all its records in place, and because of its association with ISRO, the material the archive collected could also become a blueprint for how to collect and preserve confidential records.

They found everything from top-level correspondences between industrialist Naval Godrej and Prof. UR Rao, former Chairman of ISRO, to the notes by factory employees working on their ideas. One of these items was a factory logbook, with a meticulous record of everyday work that the shopfloor employee maintained while building the Vikas engine for PSLV. It was the first of many products Godrej made for ISRO.

This would have been an exciting find for history and space enthusiasts. But to get the average employee invested in the art of archiving, Pathare and her team had to strategise.

They started using the company’s intranet to post photographs of workers across the decades and asking employees to identify them — kicking off a series of interactions and dialogues with the employees. Now, employees willingly send the archive material they think will be useful.

“That history can even be just one year old and not 50 years old is something we had to make them aware of – and we have to keep revisiting this,” said Pathare. “It’s not their priority, so Archivists have to make more of an effort to meet them more than halfway.”

Also read: ‘Whose history?’: In Telangana and Andhra Pradesh, the archives are fighting

The business of building an archive

It takes time to build openness to the archival process.

Sanghamitra Chatterjee, who set up Past Perfect in 2016, realised that every institutional archive follows a maturity cycle. If the institution or its management isn’t in the right headspace, building an archive would be an uphill battle. Especially because archivists need cooperation from all departments across the hierarchy, or else they will be stonewalled at every level.

Past Perfect starts with documenting the institution’s narrative: the process is even more intimate when it’s a family-run business. And the corporate offices require handholding and frequent reminders that an archive is not just interested in the leadership and business family.

The heritage management firm has clients from across the spectrum — from big corporations like Bajaj and Kirloskar to NGOs like Seva Sadan. In their experience, it’s important to know which department the archives come under. Usually, it’s one of three: the corporate communications department, the HR department, or the chairman’s office. The nature of the archive and its output changes accordingly. Past Perfect’s work as consultants ends with setting up the archive, after which the institution uses it in whichever way it chooses.

And contrary to popular belief, the budget for an archive is not always a stumbling block.

According to Chatterjee, it is possible to cost-effectively set up an archiving system to preserve an institution’s history.

“Whatever the budget, an archiving process can be tailor-made to it,” said Chatterjee. “That shouldn’t be what holds institutions back from creating an archive.”

Outside the public purview

Business archives are common in the United States of America: several American archives, both state and privately run, have records that chronicle business histories. The United Kingdom’s National Register of Archives and the British Archives Council have business records by industry and region. China too maintains records of all state-run businesses.

But in India, the state keeps an arm’s length from private sector histories.

“Industries’ growth that is recorded in government organisations is captured by the archives,” said Chandan Sinha, Director General of the National Archives of India (NAI). “But the archives of a corporate entity would not come to a national or state archive because by definition they fall outside their purview.”

“We are concerned with records that are generated with public funds,” he added.

Telling the story of contemporary India’s growth and innovation isn’t always seen as a historical project. That’s because much of India’s rapid growth happened post-liberalisation and it is still too ‘new’ to claim its place in public archives. And private institutional archives are stepping in to fill this gap.

While corporations are beginning to chronicle business histories, the NCBS in Bengaluru is chronicling the history of science in India. The research centre, part of the Tata Institute of Fundamental Research (TIFR) and under the union Department of Atomic Energy, runs a publicly-accessible archive. While Tata has its own private corporate archive located in Pune, the Archives at NCBS is a public archive at a government institution.

They are making private collections available to scholars. And in almost a dreamlike scenario for Indian archives, they actually promptly email documents to those who put in requests.

The Archives at NCBS recently released MS Swaminathan’s private papers, which finally shine a light on agricultural history of India. At the NAI, there are almost no records on the Green Revolution, and barely any papers from the Indian Council of Agricultural Research (ICAR), making it difficult to comprehensively look at the growth of Indian agriculture.

But the Swaminathan papers prove how the documentation of some state projects is incomplete, missing the insights of private papers that often lie collected in almirahs in ancestral homes. Some of the documents in the collection include a 1986 letter from Dr Manmohan Singh — then deputy chairman of the Planning Commission — acknowledging Swaminathan’s contribution to India becoming self-sufficient in foodgrains.

“In principle, a public archive is meant to be agnostic of the lens of the collector itself or the individual or industry that’s trying to generate it,” said Professor Satyajit Mayor, director of NCBS. “There are many ways to have private archives. Many would be selective of the way they preserve history.”

A rare find – a handwritten record of one of the early Provident funds created by Wipro pic.twitter.com/G4KPhcgMEN

— Rishad Premji (@RishadPremji) April 7, 2022

Also read: Kashmir militancy to Sharmila Tagore as brand face—Ahujasons’ road to India’s winter fashion

Multiple points of entry

A scientist’s field notes from 1982 on four animals that lived on trees — the Bonnet monkey, the lion-tailed monkey, the Nilgiri langur and the giant squirrel — is one of archivist Venkat Srinivasan’s favourite objects in the Archives at NCBS.

The story of how these valuable scientific insights were written on biblical Braille papers is deceptively simple: Ajith Kumar, the scientist, sourced the papers from a local church selling Bibles in Braille because the paper was good quality and non-blotting.

Srinivasan says this one object provides multiple points of entry: it can be useful to those interested in Kumar’s research, in Braille, or in missionary activities in the region. And the Archives at NCBS are a good catch-all for people interested in pursuing any of these lines of inquiry.

“We forget that that is the purpose in terms of function and form of an archive. Archives might end up holding heritage, but they also record processes — how things happen and why,” said Srinivasan.

The Archives at NCBS was set up in response to the death of the founder-director of TIFR, Obaid Siddiqi, in 2013. In fact, it’s physically located in his old laboratory space and is built around his own sense of the eclectic.

“We felt it was important to build that — not as a shrine to Obaid and his work, but to create a broader perspective archive that could build a basis to tell the history of modern biology in contemporary India,” said Mayor.

The NCBS is trying to situate biology in the national sciences, but it is also interested in artefacts and papers from a wide variety of people who have brought insights into modern biology, like mathematicians and physicists. They have a dedicated team looking for private collections and have also received important papers and documents by word-of-mouth.

“Our primary job as archivists is to linger and make sense of what we’ve seen. We have to linger, see, and see again,” said Srinivasan. “This is the space an archivist inhabits. Once you do that, the size of the collection doesn’t matter, the diversity of the collection does.”

The archive, which just turned four years old, received a $440,000 grant last month from a charitable fund called Arcadia, which supports the preservation of cultural heritage. They also released a guidebook in 2023 for archivists in India, with best practices for archivists as well as users of archives.

“Our aim is to eventually try and see if we can open up the archives of closed institutions,” said Mayor. “If you create a model for an archive and connect it to others, it could be very beneficial.”

And it’s not just academics who use the Archives at NCBS, but artists and activists too.

Anuja Ghosalkar, the founder of Bangalore-based theatre company Drama Queen, is a performance artist who creates documentary theatre — a form of theatre that uses memories, metaphors, and gestures as documents to build performances. “And the house of these documents is an archive: whether paper, sound, film. It’s the basis of my practice,” said Ghosalkar.

As an artist, she’s interested in archival absences. She has been working on two projects at the Archives at NCBS: one is creating an artist’s manual on how to use an archive, which she wants to eventually perform.

The other project stemmed from her research on Obaid Siddiqi. She was intrigued by a folder at the bottom of the archives called “Ephemera.” The folder contained everything from greeting cards and postcards to receipts of Chinese food that Siddiqi ate at the Bombay Gymkhana. Along with these documents, nestled among the Siddiqi papers, she found references to a scientist named Veronica Rodrigues — someone who worked closely with Siddiqi, but finds no mention otherwise. Ghosalkar found that Rodrigues was an Indian scientist of Kenyan origin who was fighting for Indian citizenship. Her entire struggle is documented in the archives and Ghosalkar is building a performance around her life.

“Institutional archives often forget, and who they forget is more exciting than who they bring into the fold. This happens with all archives, whether corporate or state,” said Ghosalkar. “I think of the archive as the greatest hiding place. Because nobody will ever find you there.”

Also read: Rose, sandalwood, petrichor—Gulabsingh Johrimal that captured Mughals with ‘Indian’ scents

The archivists’ role

Maintaining an archive is not trivial, and requires great passion. And this parallel movement over the last two decades has shone a light on the archivists’ role.

At Godrej, Pathare’s team started a certificate course in archive management in December 2022.

“You need an open, visionary archivist,” said Ghosalkar. “The archive is only as good as its people and the way it’s structured. What use is a fantastic archive when its door is always locked?”

Keeping the doors open is important. A former Godrej engineer handed Pathare’s team a gold mine when he gifted them his diaries. This employee, who worked at Godrej’s typewriter plant, was sent by the company to Germany in the early 1960s to be trained in typewriter manufacturing. He kept diaries during the process, filling them with notes and diagrams — as a part of the collaboration between Godrej & Boyce and VEB Optima, a German company, to manufacture their third typewriter model M12.

The yellow pages of the frayed notebook are filled with the engineer’s blue ink and neat, labelled diagrams. A carefully drawn letter ‘A’ in the Devnagiri script is reproduced, with instructions on how the typewriter should be built to write Hindi texts.

Years later, after the engineer had passed, the Godrej archives received three important visitors: his children, who now live outside India. They’d come to see the way their father had contributed to Indian history, in his own handwriting.

“It’s not an unreasonable thing for a family on a Saturday afternoon to say ‘let’s go check out the local archive’,” said Srinivasan. “But to get to that point, archives and archivists will also need to step out of their space and reach out to the public.”

This article is part of a series on the state of India’s archives. Read all articles here.

(Edited by Ratan Priya)