Malhari Pawar, who works with a private bank, was taking a short break after lunch under a cluster of trees at Mumbai’s Shivaji Park. Next to him was a small, but grand water fountain with two large beautifully carved basins on either side. He turned on a blue knob about a foot away and it started spouting water. He filled his bottle and had a sip.

The stone structure is one among Mumbai’s many pyaaus (public water dispensers) that came up in the island city between the late 1800s and early 1900s, most on the city’s old tram routes, as a philanthropic gesture from merchants to provide clean drinking water free of cost.

Over time, Mumbai’s pyaaus and the city’s other heritage street furniture such as its ancient milestones and bandstands have run into disrepair – shoddy relics lost in the city’s fast-paced metamorphosis into a modern metropolis. But over the past four-five years, these heritage structures and the stories associated with them are once again coming to life on the city’s streets.

The Brihanmumbai Municipal Corporation’s (BMC) heritage cell has so far restored 15 milestones from the colonial era – from Colaba in South Mumbai to Sion, which was the last point of Bombay. At South Mumbai’s Fort locality, the Cooperage Bandstand, one of the city’s last few, has been readied for live music performances once again. A bandstand is a covered public space for bands to play music in. A handful of pyaaus have started offering water to passersby once again, and the restoration of more is underway.

While the BMC is usually in the news for demolishing illegal hutments and dilapidated buildings, it has now embarked on rebuilding and renovating more and more heritage sites.

“We have completed the restoration of the milestones. Where the milestones had disappeared, we built new ones in stone with engravings. We are doing up the pyaaus and bringing back drinking water in them,” said Sanjay Sawant, who helms the BMC’s heritage cell.

“We restored the Metro fountain (the Fitzgerald Water Fountain outside Metro Cinema in South Mumbai) and the iconic Flora Fountain in Fort, and the Cooperage bandstand which was a part of the city’s recreation and culture,” he added.

Also read: August Kranti Maidan saw the birth of Quit India Movement. Now it’s getting a makeover

Heritage shaping culture, then and now

Seventy-year-old Ranaja Thatte, who lives opposite the Cooperage Garden with its bandstand, gets transported back in time whenever she sits on her terrace, listening to live music from the bandstand.

In the late 1960s and 1970s, her father used to take her to the garden every Sunday evening to listen to live performances at the bandstand. “The evening would end with him buying me a balloon,” Thatte reminisces.

But somewhere down the line, the weekly music performances stopped, and the bandstand, which was built in 1867 by the Esplanade Fee Fund Committee, rotted.

“The whole wooden structure had decayed. We had to first understand its historical references, see its character. Then we had to dismantle the whole structure and reassemble it,” said Rahul Chemburkar of Vaastu Vidhaan Projects, which has partnered with the BMC to not only restore the Cooperage bandstand, but also Mumbai’s milestones and most of the pyaaus.

“We created a stone base at the ground and restored the structure using traditional woodwork craftsmanship. The carpentry team used traditional joints, which are very unique to India. We haven’t used a single nail in the woodwork. That is the unique selling point of the whole structure,” Chemburkar said.

The restored bandstand was opened for public use in 2018. While it does host music events—the National Centre for Performing Arts collaborated with the BMC to hold a cultural festival here in March this month—it is still not a regular feature like it was when Thatte was a child.

“They should start free-for-all music festivals every Sunday like there used to be. The children will enjoy it. But it’s not that the bandstand isn’t being used. People use the space in their own way – some do yoga exercises there, others, meditation,” she said.

BMC’s Sawant said, of the other bandstands in the city, the one at Veermata Jijabai Bhosale Udyan (the Byculla Zoo) is in good condition, but the Bandra bandstand needs to be restored.

Also read: 60-second heritage – Instagram is breathing life into India’s old cities, buildings, stories

Obelisks that tell a tale of Mumbai with bullock carts

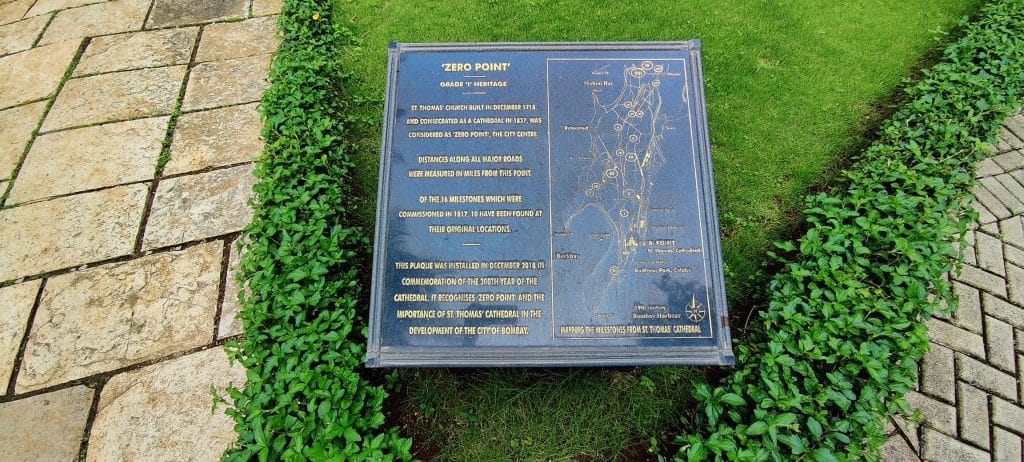

At the St Thomas Cathedral in Fort, a visitor is busy reading information off a plaque outside the church and taking a picture.

The cathedral, tucked away in a corner of a bylane near Horniman Circle, was once the focal point of a Mumbai that only knew bullock carts and horse-drawn carriages as modes of transport. The plaque that the visitor is poring over declares that this was the city’s ‘Zero Point.’

“A couple of years ago, when there was some restoration work underway at the church, the plaque was also renovated for it to be boldly visible. There has been a steady stream of visitors over the past few months. People come to read the plaque and take a picture, and then also see the church from the inside,” Saurabh Patkar, the security guard of the cathedral, said.

In Bombay as it existed then, there was a battlement wall inside which was a native town, Chemburkar said.

“There were gates, and at the centre was a church – St Thomas Cathedral. Then the battlements were demolished and the city extended till Sion. The modes of transport were Victorias, bullock carts or by foot, before the trams came. The measuring unit was the mile, and the zero point was the St Thomas Cathedral,” he said. All the other milestones across the city said, ‘One mile from St Thomas Cathedral’, ‘Two miles from St Thomas Cathedral’, and so on.

After motorised transport increased and trams gradually disappeared from Mumbai’s roads, the milestones had no use. They just became historical markers, giving a glimpse into the infrastructure management system of those days. But they were neglected until the BMC and Vaastu Vidhaan completed their restoration this year. According to the BMC, they restored 11 milestones that they could find and had to build five others that had completely disappeared with the same stone and carvings.

The milestones also have a QR code and the plan is to launch an app with information on all the milestones, Chemburkar said.

Also read: Jamali Kamali, hijron ka khanqah, Sarmad’s tomb — Delhi history’s safe spaces for LGBTQ

“God of heritage in small details”

Gangadharan Menon, a Mumbai-based senior art teacher, found out about the milestones only recently when they were restored, tied into a circuit and became a part of the offerings of various heritage walks through the city.

“A city that doesn’t look after its small things isn’t really doing its job. It’s only when the pyaaus and bandstands are restored, you are making the city’s heritage relevant in its culture today,” Menon said, adding, “The God of heritage is in its small details.”

The pyaaus, for instance, each have unique details, an umbrella here, a clock tower there, a different water dispensing mechanism in each one, a place at the bottom to collect spillover water for animals to quench their thirst.

“Unfortunately, there is no proper documentation of pyaaus. They were street furniture, there was no proper designer though they were designed intricately. We did proper documentation and realised there would have been about 100 pyaaus in the island city. The Mumbai suburbs were earlier villages and depended on wells,” Chemburkar said.

“Now, what we find are about 50 pyaaus. The ones that can be revived with some effort are about 25,” he said. Four have been restored and there is a plan to restore 18 others with the BMC.

The pyaaus that have been restored have once again become points of free drinking water.

Pawar filling his bottle at the Ramji Setiba pyaau at Shivaji Park is testament to this.

“Someone stole the tap about 20 days ago. Even then, everyone who comes to Shivaji Park fills their water bottle here. There is no other option for free drinking water,” he said.

(Edited by Neera Majumdar)