In Nagaland’s commercial district of Dimapur, a quaint little café, Shiro Roastery, decked in Instagram-able white, minimalist interiors serves single-origin coffee along with an assortment of delectable foods, including ‘exotic’ options such as matcha Japanese cheesecake. A few kilometres away, two professional chefs operate a French patisserie-style café.

Nagaland is witnessing an unprecedented surge in cafés over the last two years, primarily in Dimapur and the capital city of Kohima, transforming a traditionally tea-drinking community into smart and informed coffee drinkers.

The trend has spawned a new brand of ‘coffee-preneurs’, predominantly millennials and Gen-Z entrepreneurs. And they are not afraid to experiment. Some owners take pride in their puritanical love for the bean, serving coffee and nothing else. Others attract customers by updating their menus every day.

“I think with this generation, we’ve really started to think about spending more time with people, giving ourselves time,” says 26-year-old Keny Metha, the newest entrant in the café boom. She opened Glutton in Kohima on 21 July, which is “mostly inspired by Japanese food for its use of simplicity”.

As the winds of entrepreneurial change blow over Nagaland, youngsters are seeking ‘apolitical’ spaces to hang out. It’s a significant cultural and generational shift in Naga society which, for decades, was under the grip of insurgency.

Also Read: ‘I speak Sanskrit, do you?’ Gujarat will host its first Sanskrit Literature Festival now

Bringing the café culture to Nagaland

One of the trailblazers at the helm of this trend is former government employee, Lichan Humtsoe. He quit his secure job with the state department of land resources to start Été Coffee in 2016. A few months later, school teacher Dili Kheko, who taught environmental sciences, traded the classroom for a cafe with D’cafe.

Both Humtsoe and Kheko, who are in their 30s, felt the time was ripe for change. It wasn’t that Nagaland was bereft of cafés prior to 2016, but they lacked the ‘chilling’ culture that thrives in other cities like Bengaluru, Mumbai and Delhi where people sit for hours with a good hand-picked blend of coffee.

Kheko, who had spent most of his childhood and college life in Shillong, was inspired by the café culture in the Meghalaya hill station. “In 2012, when I came back to Kohima, there were a few restaurants but there was no good coffee shop,” he recalled. There were some cafés but the teacher-turned-café owner dubbed them to be “old and traditional” ones, which didn’t want people to stay for long”.

“Naga culture is such that we are not really used to going out. The older generation still doesn’t want to spend money to have family meals outside,” said Kheko.

Dimapur, which thrums with commercial activity, is an obvious choice for coffee-preneurs. But so is Kohima. “Though it’s mostly a government salary-based community, the younger generation wants to go out and meet their friends, which is pushing the trend,” he explained.

Today, cafés in Nagaland are the ‘it’ places filled with the happy chatter and clatter of friends catching up and small businesses setting up their pop-up stores.

Also Read: World’s largest religious monument will soon be in India—with the help of Ford heir

Enter the café-preneurs

The success of the cafés started by Humtsoe and Kheko inspired younger people like 26-year-old Keny Metha, the owner of Glutton. Before opening her café last month, she had tested the waters with a pop-up restaurant that served a mixture of Japanese, Korean and Naga cuisine, which she ran for three months in 2019.

Underlining the generational shift in the Naga society, she credited the ‘first movers’ for paving the path for future café entrepreneurs.

“Eté Coffee, Nagaland Coffee, and the way they educate people about how their coffee beans are grown, what goes into just one cup of coffee, has generated interest among customers,” Keny said enthusiastically. It’s early days still for Glutton, which is barely a month old, but her eatery is almost always full and open till 7 pm.

In 2020, when restaurant owners were questioning the future of the industry due to the pandemic, Akani and Tokali Yepthomi decided to open A.T. Patisserie. The sisters, who are certified patisserie chefs from Le Cordon Bleu (Sydney) and Sunrice Global Chef Academy (Singapore), had been operating out of their home for five years before they decided to take a leap of faith and open A.T. Patisserie. They wanted to give their customers a chance to “experience authentic cakes and desserts”.

Operating from a spacious place in Dimapur, the Parisian café is frequented by “the coffee nerds, the freelancer/artists/influencer and the first-daters both young/old,” said Tokali. Apart from serving pretty pastries, cakes, biscuits and chocolates, A.T. Patisserie also has Korean and continental cuisine on its savoury menu. And almost all their offerings are picture-perfect.

Coffee-preneurs wield Instagram with ease and expertise to create the right amount of buzz. A hot favourite in Dimapur is the Instagram-able Shiro Roastery inspired by owner Rowang Debbarma’s travels across Southeast Asia. After quitting his job as a photographer at Amazon Prime in Bengaluru, he returned home to set up Shiro Roastery in February 2022. The café isn’t limited to brewing its own coffee, it also sells an exquisitely-designed range of custom merchandise such as T-shirts, tote bags and notebooks.

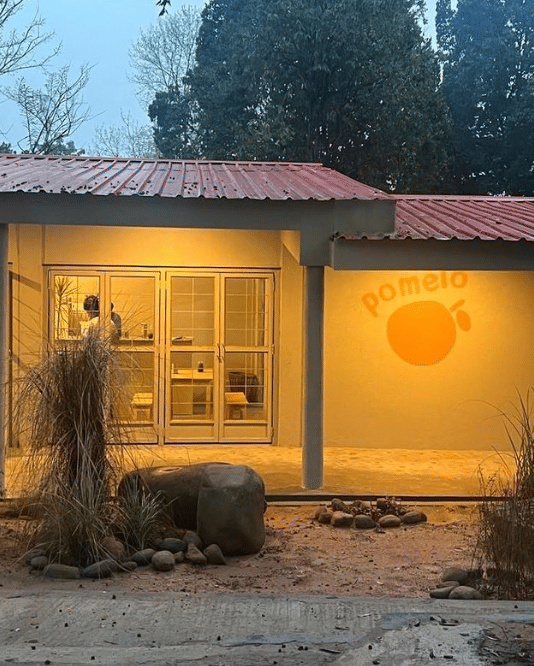

Another café in Dimapur, Pomelo, may be deliberately rustic but is no less Instagram-worthy. It took shape during the pandemic when one of its founding partners was deliberating over whether to stay in Delhi and work as a consultant for restaurants or return home. Ultimately, Kumli Kichu opted to become a chef and partner at Pomelo, which opened its doors to patrons in Dimapur this April.

“We see a lot more cafés opening up after Covid-19. One factor is that a lot of young people came back home and stayed on,” says Kichu.

She also attributes social media as a strong factor driving the café trend. “In terms of food, starting from mukbang to all things Korean, kids want to eat what their idols on Instagram are. So, the demand for picture-perfect drinks and food is what drives, inspires and convinces people to open up new spots,” she added.

Pomelo offers a slightly different menu every day ranging from Middle Eastern to Korean and American-inspired selections.

For ‘industry leaders’ like D’café, the pandemic didn’t put a dent in the momentum. The café underwent an overhaul earlier this year to expand its sitting space to 70-80 people—twice its previous size. That said, owner Khekho has observed that people have “become more calculative about their expenses”.

Also Read: Ambedkar in a savarna mundu? Why Babasaheb’s clothes matter

The government’s coffee push

Nagaland’s café boom is generating jobs and boosting the local economy too.

Été Coffee, which has expanded to two outlets in Kohima in six years, has opened a barista-training institute last January.

“We have helped 11 cafe owners to establish their cafes, sponsored 19 individuals to get coffee-skills training under our self-styled fund and have also trained and deployed baristas in several cafés across the region,” said Humtsoe, who claims that the Été Coffee School is one of the first-ever coffee schools in northeast India.

The mushrooming of cafes isn’t confined to Dimapur or Kohima. “We are seeing cafes coming up in small towns like Pfutsero, Longleng and bigger towns like Wokha and Mokokchung,” Homstoe said.

While it’s largely individuals promoting the café culture in the two biggest towns in Nagaland, the role of government comes into the picture as the state witnesses a shift from being a tea-drinking community to embracing coffee.

Quietly stirring the coffee revolution in other districts of Nagaland is the land resource department — entrusted with the task of promoting coffee plantations in the state. Like two sides of the same coin, the department knew that to make farmers sincerely embrace the shift, it had to inculcate coffee-drinking culture and show the growers the end result of their labour.

“With financial support from the state government, the department has identified 11 young entrepreneurs from across 11 districts and promoted one coffee café each in the area,” said Albert Ngullei, the additional director of the Land Resource Department.

Apart from Kohima and Dimapur districts, he claimed the coffee cafés promoted by the department were the first and only coffee cafés in 11 districts of Nagaland.

“Initially, the department provided barista training to unemployed youth, helped them set up the café with infrastructure and coffee machinery,” Ngullei added.

There’s no government data on the number of cafés in the state. With a new player in town every other day, even cafés owners have a tough time keeping track of their competitors.

Kohima-resident and regular café hopper Teyangsen Imchen said there are roughly around 15 cafés in the capital itself, which has an estimated population of 2.9 lakh (as per Aadhaar data till December 2020).

A.T. Patisserie said there would be between 20-50 cafés in Dimapur, where the population is a little over 4 lakh (according to Aadhaar data).

Also Read: Another year, another deluge in Assam — why northeast floods are getting grimmer

A ‘peaceful’ state with coffee

For a state coming out of the shadows of decades of insurgency, a booming café culture indicates a return to normality.

Nagaland University’s economics professor Kilangla Jamir attributed the rise of café culture to the exposure of Naga youth to city life outside the state and the shrinking number of government jobs.

“Earlier, people hardly went to eat out,” she said. Today, the influx of Naga youngsters going to other cities to study or work has shot up. “When they come back home, they want to have continuity of what they experienced outside,” the professor explained. “On the other hand, employment opportunities are not the same as before. Hence, from the supply side, people are starting to undertake such business projects.”

But above all, it’s perhaps the peaceful conditions in the state that’s allowed Naga society to effortlessly embrace this urban lifestyle of leisurely spending time at a café.

“Earlier, going outside or eating outside late at night was quite dangerous. Now, the atmosphere has become comparatively peaceful, so businesses are booming. This is one of the major reasons for the growth of cafés in the state,” she explained.

On a rainy summer evening in Kohima, when 24-year-old Imchen ran to take shelter in a small roadside café, these overarching macro changes were certainly not on her mind. But it’s these tangible changes in the cultural fabric of Naga society that made it possible for her to randomly walk into the cafe. “I had a cup of coffee and a croissant — one of the best I’ve ever eaten. The combination of the sound of the rain, the smell of coffee, and the relaxing background music while watching people on the street made me think about how much my town had changed,” she said.

(Edited by Neera Majumdar)