New Delhi: There will be no Khalistan, declared Rajiv Gandhi. As slogans like “Rajiv Gandhi ka Ailan/Nahi banega Khalistan (Rajiv Gandhi has announced, Khalistan won’t be created)“ were spread through on-ground rallies, an ad campaign juxtaposed public fears of Khalistan-related unrest with distinctive imagery of barbed wires, crocodiles and broken chairs, as well as descriptive pieces about the apparent risk that the crisis in Punjab would lead to a fractured, divided India.

And it paid off. In December 1984 — hardly more than a month out from the anti-Sikh riots in north India that led to the massacre of thousands following the assassination of Prime Minister Indira Gandhi — her son Rajiv took up the mantle and led the Congress to a dominant election victory with 414 Lok Sabha seats.

The victory was achieved on the back of a multitude of factors and has since been contextualised by numerous events, but one noticeable aspect was the party’s use of political advertising in print media to popularise Rajiv’s slogans and messaging.

According to the ads, the future they warned of — darkened by the shadow of separatism — could only be prevented by giving “strength”, “unity”, and “ideology” a “hand”, an explicit reference to the Congress’s symbol.

Let me unmask Rajiv Gandhi's communal mind-set.

Leading election in Dec 1984, he unleashed communal campaign in Print!

Created by his cousin Arun Nehru's friends in Rediffusion, the campaign depicted Sikhs as enemy, out to divide and destroy India.

This was one of that series: pic.twitter.com/Fjaq3Cl4zQ— Raghunath AS (@asraghunath) May 5, 2019

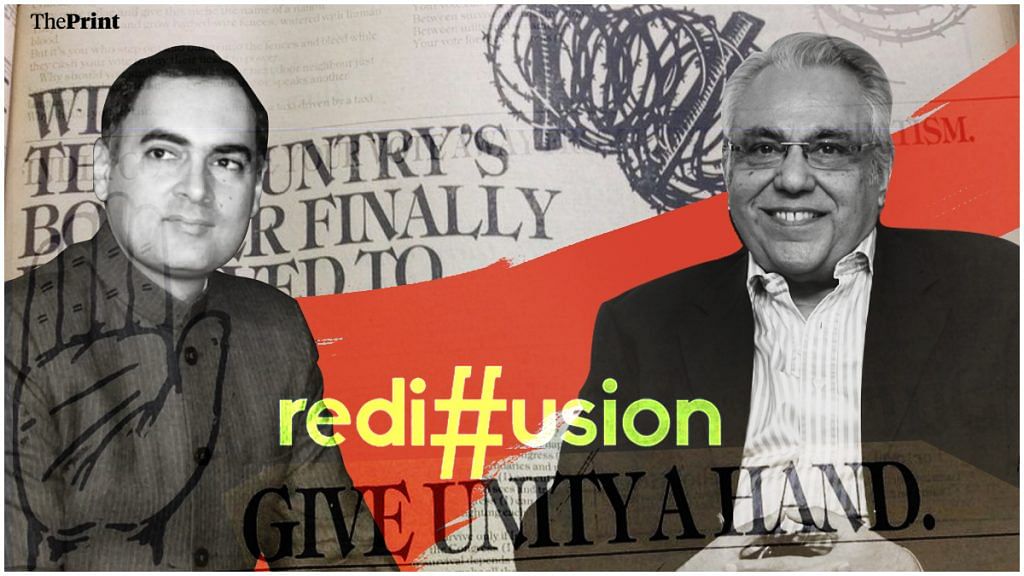

Published by newspapers including Hindustan Times and later compiled and documented by former journalist Raghunath A.S. in 2019, the advertisements were the brainchild of independent ad agency Rediffusion, which was established in 1974 by Diwan Arun Nanda, Ajit Balakrishnan and Mohammad Khan.

In a telephonic interview with ThePrint, Nanda revealed that Rediffusion began creating campaign ads for Rajiv Gandhi in 1983 under certain conditions, and the relationship soon went far beyond that of a standard professional client, transforming into a “very strong bond” between the two.

Also read: Poet Kaka Hathrasi’s music magazine, Sangeet, struggling, not in tune with times

‘Just us, the agency, and him, the client’

Political advertising and the relationships between political parties and ad agencies in Independent India have lacked the extensive recorded history they merit. However, the extent of the collaboration between Rajiv Gandhi and Nanda is a fascinating place to start.

“We read every single article and book on political advertising that had been published both in India and outside. [As part of the conditions] I did not deal with anybody in Congress except him and only him. No committees, group of ministers or advisers, just us, the agency, and him, the client,” Nanda told ThePrint.

As such, Nanda wore multiple hats, not only as a creative ad agency head but also as a research-intensive political strategist to ensure that the advertising had maximum impact for Rajiv’s campaign.

“After our first meeting with Rajiv, we used to conduct research quarterly, the largest-ever project of its kind in India, and we used to present it to Rajiv once a quarter on a CD, of which no [additional] copies were ever made. Rajiv would own one copy on his personal laptop, and another remained at the agency with me,” Nanda said.

The research, Nanda detailed, went into “sensitive areas” ahead of the polls, such as public perceptions around Sonia Gandhi’s Italian heritage. “Her nationality was under question at that time,” he said.

The impact of this research was visible not only in the advertisement content but also in the election results, according to Nanda. “We created a simple statement. It had never happened before or ever afterwards, that the Congress had won 415 (sic) seats in the Lok Sabha. That speaks to our performance.”

The two Aruns

Contemporaneous reporting by international media house The Christian Science Monitor had detailed how Rediffusion’s “high-powered” creative work was pioneering for Indian politics, leading to varied public reactions, from “offensive” to “baffled”.

Moreover, this January 1985 article singled out “two Aruns in waiting” — Arun Nehru and Arun Singh, personal aides of Rajiv Gandhi, with the former also being a cousin — as key figures behind the development of the Rediffusion-Rajiv partnership.

However, Nanda said that while Arun Singh was involved in the 1984 campaign, Arun Nehru played little role beyond setting up the initial meeting between Nanda and Rajiv, despite his “strong” personal relations with Nanda.

“Arun Nehru had been a client of Rediffusion when he worked in Jenson and Nicholson Paints. I had dealt with him earlier in that capacity. Apart from Rajiv and the agency, nobody else was involved, except for Arun Singh, who later became defence minister,” he added.

‘Nothing to do with communalism’, end of political work

Nanda said that the slogan “Rajiv Gandhi ka ailan/Nahi banega Khalistan” was not a Rediffusion creation, but emphasised the Congress’s stance of ensuring that India was not “parcelled out” due to the “disturbances” in Punjab and Assam.

He also rejected Raghunath A.S.’s label that Rediffusion’s campaign ads were “communal” in nature. “[The ads] had nothing to do with communalism, it had to do with a strong, non-divisive India. Whatever we did, we would not let the country get fragmented at any cost. Please remember his mother had been assassinated, his time was a question mark in terms of safety especially of politicians,” Nanda added.

Rediffusion continued its collaboration with the Congress for the 1985 Punjab elections and the 1989 general elections, but Rajiv Gandhi’s assassination in 1991 marked not only the end of the creative and strategic relationship, but also the end of any political advertising work from the agency entirely.

(Edited by Rohan Manoj)

Also read: Flop Show — Jaspal Bhatti’s 1989 satire spared no one, and the common Indian loved it