Rizwan tosses his mid-range smartphone in the air. “Madam, this phone is the movie hall of today!” he says. The 34-year-old breaks into laughter over the clever quip, as his friends chortle and cackle in agreement over cups of tea and Parle-G biscuits. “You’re absolutely right brother!”

Bollywood is in the middle of a protracted death throe and no amount of CPR seems to be helping. It’s people like Rizwan and his friends—all shopkeepers from Khurja in Uttar Pradesh—who are delivering the diagnosis every Friday. From tea stalls in Bulandshahr and Khurja to armchair critics on Twitter and OTT gluttons on their couches, the ominous whispers of a decaying Bollywood are growing louder and louder.

And Bollywood is panicking.

India’s relationship with Mumbai’s filmy duniya is rapidly changing, facilitated by the rise of OTTs, the ‘Jio revolution’ that allows people to stream content on their phones with ease, the demise of single screens, surging ticket prices, sinking star power, and stiff competition from South India.

The consensus among Rizwan and his friends is that Bollywood has “squeezed” the soul out of Hindi films. “It’s all about sex, violence and nasha,” Rizwan says. The last film he saw at a cinema hall was Dhoom 3 in 2013. Bollywood needs a blockbuster—desperately.

In Mumbai, the tension is tangible. Sweat glands of producers are working overtime, though humidity and heat are not to blame. Young film crew members with big production houses carry a frown of anxiety on their faces. They talk about budget cuts and potential firings in the coming months.

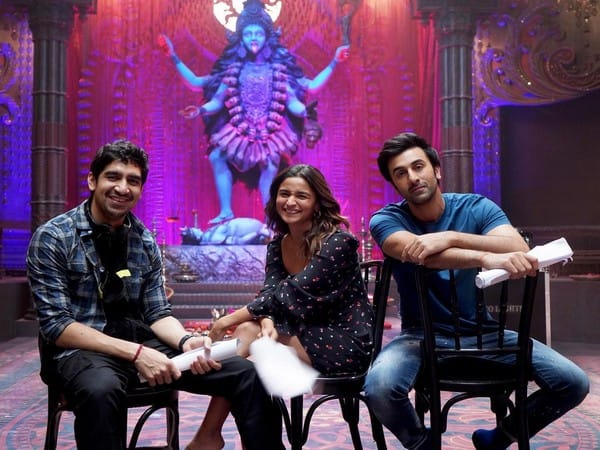

Which is why so much hinged on Brahmāstra being a roaring success at the box office.

Also read: Amul cartoon for Squid Game, day off for Money Heist — Indians finally binging world TV shows

‘We make bad films’

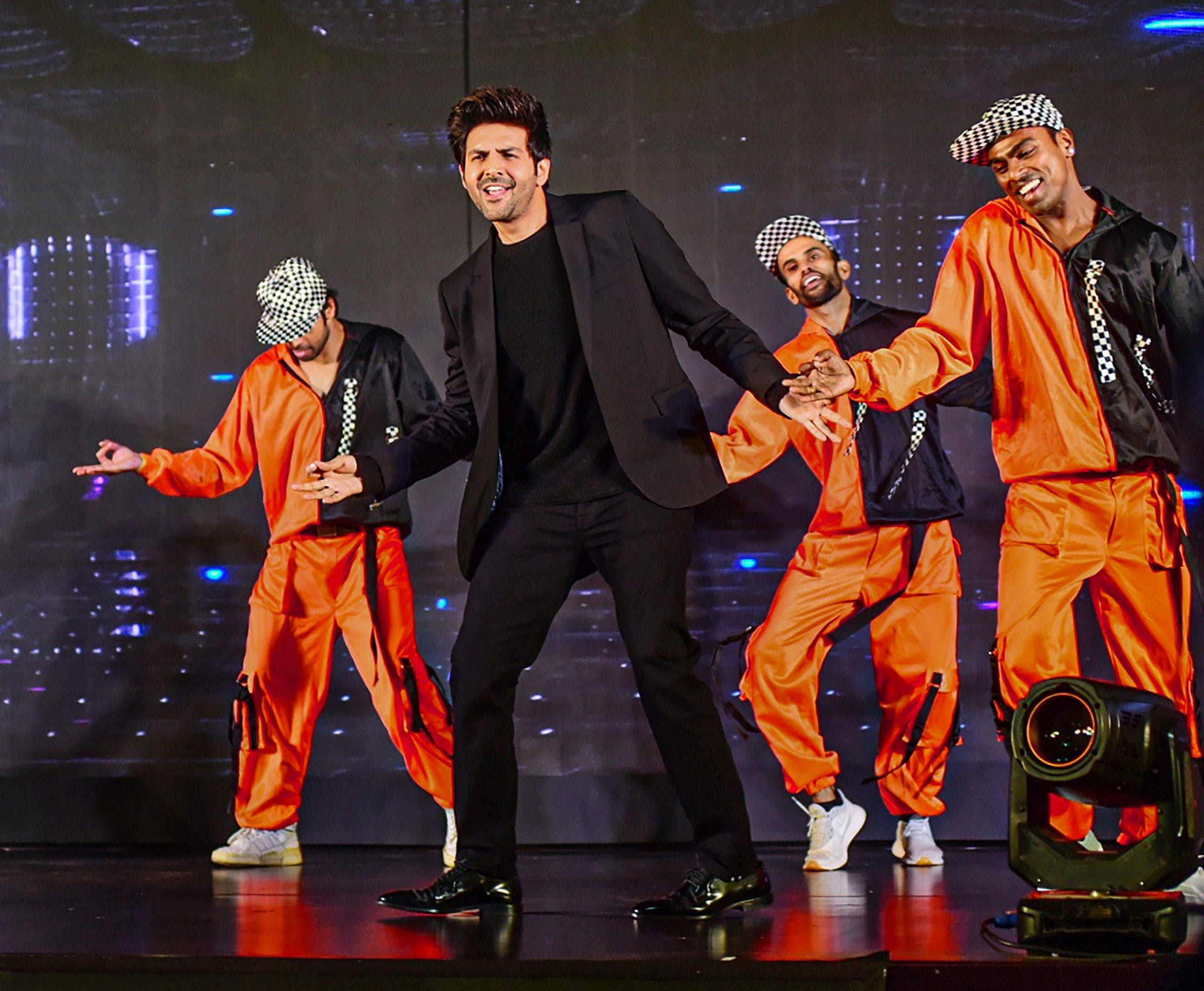

Shah Rukh Khan flexing his biceps in a farm, Tiger Shroff doing mid-air splits and Ayushmann Khurrana tackling yet another social evil do not make blockbusters anymore. Industry insiders insist that the slew of box office failures can be captured in two words: Bad scripts.

“We make lousy films that deserve to tank anyway,” says actor Naseeruddin Shah.

Covid drove the point home.

“How do you tell stories to a shattered world?” asks writer and director Mahesh Bhatt. “When Covid brought the world to its knees. All institutions, including cinema, were brought down to confront the inevitability of mortality. And the entirety of mankind is based on escaping the inevitability of the end. But in the last two years, the world has been shattered.”

Falling footfall is not exclusive to the post-Covid world, though, with many arguing that due to its own hubris and failure to read the public pulse, Bollywood has reduced itself to a niche medium from a mass medium.

The culture of not honing writers or directors has also come to bite the industry in the back. And OTT platforms with their bouquets of shows—many compelling and well-produced—are nipping at Bollywood’s heels like a persistent dog. Many blame the old guard for failing to hone their skills or nurture new talent. It’s not just the plot, even songs and dialogues have lost their zing. They are at best, tepid, and at their worst, highly forgettable remixes.

“Dialogue in movies has turned into usual conversations, which doesn’t stay with the audience. We’re used to watching that drama, that dialoguebaazi. The industry is churning out factory-produced, lifeless songs. Earlier films had soulful songs. Now, I cannot think of any (song) right now with a long shelf life,” trade analyst Taran Adarsh says.

The song, Kesariya from Brahmāstra is one of the more recent offerings. But its lyrics, especially the refrain with random Hinglish phrases such as ‘love storiyan‘ was heavily criticised.

“Earlier, we used to tailor-make music for the film by sitting with the music director. Now, we’re given a mix of 40-50 songs, and choose a track best suited for us,” says Aneez Bazmi, director and producer of Bhool Bhulaiyaa 2.

Screenplay and scriptwriters, however, are not happy being made scapegoats for Bollywood’s decay. Blaming the scriptwriter is an easy excuse to gloss over the systemic problems that have plagued the industry for decades, they said.

“Fact is that writers are not respected in this industry. A writer’s average remuneration here is 2 per cent of the film’s budget while in South India, it’s 5 per cent,” said a scriptwriter and consultant who did not wish to be named.

Since the ’90s, Bollywood started prioritising song and dance over a convincing story. “It is very routine for a director/producer to come up with five action sequences with a star in mind, and ask writers to flesh out the plot within 15-20 days. Do you think anyone can write well in that time frame?” the scriptwriter added.

But while Bollywood is mechanically churning out films like a factory line, Hindi movie watchers are gobbling up content from all over the world and also from South India. And OTT platforms like Netflix and Amazon Prime Video were more than happy to step in with original content.

Also read: Pushpa to Bhool Bhulaiyaa 2—Covid altered Indians’ entertainment buds, masala movies are back

OTT steals audiences

Rizwan got it right when he said that the phone is the new movie hall.

“I once watched a movie every week, but now I watch shows on my phone,” says Durgesh Kumar, a Bulandshahr-based driver. The last film he watched was Sanam Re in 2015—at a single screen in Bulandshahr.

It was Apple CEO Tim Cook who made a prescient comment to Mahesh Bhatt on the dominance of smartphones when they met in Mumbai. “He raised his phone and said, ‘All you need is this phone… The gatekeepers of yesterday are going to be irrelevant’. There was a hierarchy that has continuously been battered by new media, which consumers now have access to,” Bhatt says.

And some Hindi films have done good business on OTT platforms. Though ThePrint couldn’t access OTT numbers for theatrical releases, media consulting firm Ormax’s Gautam Jain gave examples of three films that did well on OTT. Gehraiyan was watched 22 million times on Amazon Prime (subscriber base of 13-14 million), while the Jadugar series on Netflix had 7.4 million views (subscriber base of 5-6 million) and Good Luck Jerry was streamed 13.4 million times on Disney+ Hotstar (subscriber base of 58.4 million).

But it can’t be an apples-to-apples comparison. “Box Office is in stage 3 of its growth. It is stable while OTT is in stage 2. There are multiple tailwinds helping OTT like increased subscribers on a daily basis, regular subscribers increasing time spent on the platform as well as new subscribers,” Jain adds.

OTT and smartphones have freed people from the tyranny of expensive multiplexes.

Also read: Lagaan to Jhund, how does India pick sports films? Dalit stories are starting ‘second innings’

Fading star power

Diamonds may be forever, but stars aren’t.

Even the biggest and brightest stars are failing to pull in crowds let alone convince fans to shell out money to watch their films for the second time. If they were sales personnel, they would have been fired for failing to meet their yearly targets.

The most revered stars in Bollywood have been confronted with the mortality of their stardom. Superstar-led films such as Aamir Khan’s Laal Singh Chaddha, Akshay Kumar’s Samrat Prithviraj or Raksha Bandhan, and Ranbir Kapoor’s Shamshera failed to get encouraging opening weekend numbers.

This has led to a pushback in the industry. Sources told ThePrint that producers are increasingly reluctant to sign on stars at their current fee. They are reportedly forcing them into backend deals, where a part of the remuneration comes from the revenue of the film.

“Some of the biggest stars have had to cut their fee by 20-30 per cent,” a script consultant says. Entertainment reporters and producers confirmed this trend.

“There’s increasing animosity towards anyone who’s charging way too much,” says Salil Acharya a well-known radio jockey based in Mumbai. “The thing is, the budget of the movie would be, say, Rs 120 crore, but the public can clearly see that only Rs 50 crore have been invested in production. So even the public is demanding more transparency and accountability now.”

Social media had a role to play in this. It has demystified our stars and muted their ‘powers’. Today, fans can track their favourite stars on Instagram, watch them do mundane tasks or get to know their views on some trending topic on Twitter.

And this is where their marketing strategy has gone wrong, says distributor Rahul Merchant who owns Luminosity Pictures. “Look at Hollywood, you will not find any leading actor dancing so much on social media. A mystery needs to be maintained.”

There was a time when fans invested time to find out where their favourite actors went to party, what they were wearing, and what they ate. “Now it’s all served to them on a platter,” says Merchant, who has been working in the film industry for two decades.

Now, fans want more: A compelling plot, a stellar performance. They want to be entertained. As a result, there is a growing disconnect between Bollywood and its viewers.

There was a time when superstars had a simple calling card: Amitabh Bachchan was an angry young man, Shah Rukh Khan was the romantic hero, Emraan Hashmi the ‘serial kisser’ and Kangana Ranaut the outspoken but messed-up woman. But that is no longer the case.

“Over a period of time, stars broke their image by taking on a broader range of roles. By doing that, their brand starts to dilute. People don’t get their dopamine hit, and this in turn generates dissonance. They’re no longer brands, they’re just popular actors,” says Vishek Chauhan, a writer about film trends and proprietor of a single-screen theatre in Bihar’s Purnia.

Also read: Bigger, more profitable — How South Indian film industry took pole position from Bollywood

Then it all went south

Films from South India, however, are dancing and singing their way to the bank: Rs 400 crore, Rs 255 crore, Rs 100 crore. These are not the box office numbers of Hindi films starring the biggest names, but of Hindi-dubbed versions of KGF 2, RRR and Pushpa respectively. Their total worldwide box office collections crossed Rs 2,800 crore.

Collectively, the three films have made Rs 755 crore in just Hindi dubs, which is more than the worldwide box office collections of their Bollywood counterparts: Bhool Bhulaiyaa 2 (Rs 260 crore), Kashmir Files (Rs 341 crore) and Gangubai Kathiawadi (Rs 132 crore). Brahmastra has given Bollywood a chance to balance the scales a bit.

According to Ormax’s The India Box Office report 2022, Hindi cinema contributed 34 per cent (the highest) to the total box office of 2022 till July. But of this, 41 per cent was from the Hindi dubbed versions of South Indian films.

The contribution of other languages was no less. Telugu films stood at 24 per cent, Tamil at 15 per cent, Kannada at 8 per cent and Malayalam at 6 per cent.

The pandemic led to content exploration, and the Hindi-speaking population stumbled onto South Indian content. Aanya Roy from Mumbai is a die-hard Salman Khan fan. She grew up in Bahrain, but relocated to Bollywood’s beating heart earlier this year. She enjoyed “typical” masala films. But bored with Bollywood’s banality, “lack of talent” and reduction of women to “eye candy”, she developed an interest in Southern movies, which captured the heart of the Hindi heartland during the pandemic years. With the discovery of South Indian cinema, former Hindi film buffs realised what they had been missing all along: Relatable characters, well-rounded stories and good acting. In short, entertainment, entertainment, entertainment.

New converts that ThePrint spoke to said they had a certain stereotype of Southern Indian movies, which has since been shattered.

The mirage that South cinema is all about mindless action movies where bullets are turned on their heads by making wind out of thin air has been broken. “We all have, at some point thought Shivaji: The Boss and Suryavamsam represent the entirety of South cinema, as those are the only movies we could watch on cable TV,” says Anmol Taneja, a Gurugram-based scriptwriter and aspiring filmmaker.

That changed when he watched Kumbalangi Nights in 2019. “It was such a beautiful experience. Since then, I have been following Southern cinema. Especially new-age Malayalam cinema,” he added.

Mohd Tasim Khan, a 35-year-old shopkeeper in Bulandshahr, is also a fan. “You can watch them with your family. They uphold our Indian traditions and values unlike Bollywood” he says.

This popularity is only skin deep. The most successful so far has been the Telugu industry, but numbers suggest only a very creamy layer of films have seen the light of success. Of the 118 films released in the Telugu language from January 2022 to August 2022, only 10 were successful.

Unpromising box office numbers had actually forced the Active Telugu Film Producers Guild (ATFPG) to go into a huddle and re-think their box office strategy, pausing production for a while.

Stars like Prabhas (Radhe Shyam), Chiranjeevi and Ram Charan (Acharya) have also endured the bitter taste of flops this year, just like Akshay Kumar, Aamir Khan, Kareena Kapoor, Kangana Ranaut, Ranveer Singh, and Ranbir Kapoor.

“Hindi cinema watchers are simply in the honeymoon period with South Indian content, but check the numbers in the peninsula. The industries there are also struggling in the post-pandemic era,” says Ken Ghosh, director of films like Ishq Vishq (2003), Fida (2004), and Chance Pe Dance (2010).

This is a sentiment director Anurag Kashyap also shares. In an interview that went viral, Kashyap said that if only two Hindi movies worked commercially, then only Two Telugu movies managed to create magic at the box office, along with one Tamil and one Kannada film. “You wouldn’t know how many South Indian films are tanking,” he had said.

South Indian films are making the most of this honeymoon period in multiplexes across India, which have eaten into the revenue of single-screen cinema halls. Many industry experts believe there’s a link between the demise of single-screen cinemas and Bollywood’s poor showing.

Also read: In a world of Disney+, HBO Max, Netflix losing subscribers is a sign of less promising future

Single-screen crisis

By the year 2000, India had around 12,000 single screens, according to Nitin Datar, president of the Cinema Owners and Exhibitors Association of India (COEAI). Before the pandemic struck, their numbers had halved to 6,500. And Covid sounded the death knell. “As single screens dwindled, multiplexes rose from zero to 3,500 screens. Covid washed out another 25-30 per cent single screens all over India,” he says.

Cinema experience used to be a lot more egalitarian before multiplexes became the norm. Yes, there were divisions—the financially affluent would sit on the balcony, while the less well-to-do bought first, second- and third-class tickets below. But everyone could go to the movies.

Multiplexes—where the cheapest tickets are priced at Rs 180—alienate a section of the population. For large swathes of the population, catching a film on the big screen can no longer be a spur-of-the-moment treat.

Vishek Chauhan says on 23 September when tickets were cheaper than ever, his cinema saw more footfall for Brahmastra than on day one

“We have deprived the labour class of entertainment. Have you ever spotted a rickshaw puller at a multiplex?” Datar asks.

But the CEO of multiplex giant PVR disagrees. Kamal Gianchandani says the ticket prices are not expensive and Rs 240 is the average price in India.

As single screens shut down, a section of Indians, especially those from the hinterland, has been deprived of the quintessential experience of munching on popcorn and cold samosas at the movies.

Shiv Singh, Netram and Srinivas are three cycle-rickshaw pullers in Uttar Pradesh’s Shahjahanpur. They fondly talk about the times when “movie halls” were accessible to them. “Anyone and everyone we know would sit in the hall and sing and dance along with the movies. But now, there’s no cheap hall in Delhi, and all five screens in our village have shut down,” Netram says.

In its heyday, hundreds of people would gather at Vishal Cinema in Bulandshahr city, which had the capacity to seat 600 people. Today, its colourful facade and billboards are tired and worn. And its proprietor, 76-year-old Rakesh Kumar, can barely fill it to 10 per cent of its capacity.

The films that have done well this season have been RRR and KGF 2, says Sharma. Brahmastra was the only Hindi exception. But even then, there were no ‘house fulls’.

“On Friday, I sold 241 tickets, 171 on Saturday and 204 tickets on Sunday for Brahmastra,” says Sharma. On Monday, he sold only 47 tickets.

Sharma blames the boycott trends as the number one reason for a drying business. “Hindu-Muslim issue has increased a lot. These stars say all kinds of nonsense, like this Ranbir Kapoor’s beef-eating dialogue. What’s the need of hurting Hindu sentiments? All of this is bad for business,” he says, flustered. “People are just not interested in giving money to Bollywood.”

There was a time when Sharma’s biggest competitor was Alpana Cinema, barely a kilometre away. It opened its doors in 1971 but shut down in 2018.

“The Jio revolution changed the entire game,” points out Anoop Agarwal, the proprietor of the talkies. Reading the market right, Agarwal says he got out of the business at the right time and opened a mobile store in front of his now-defunct theatre.

For years, the demise of single screens went unnoticed. By the time the industry woke up, the death knell had already been sounded.

Ormax’s Gautam Jain says box office numbers continued to grow due to rising prices. “Multiplex ticket prices were going up, box office sales were growing too. But footfalls were stagnant or falling,” he says.

Single-screen exhibitors also complain of discriminatory behaviour from distributors, who ask for a minimum guarantee before giving them a reel. “Shamshera asked for a minimum guarantee, and so did Liger, so I simply didn’t run those movies. They (distributors) were asking for Brahmastra too, but later relented,” Sharma says.

In the meantime, the Multiplex Association of India has been singing all is well, and finds nothing noteworthy to discuss on the consumption trends. “Hindi box office is going strong. In fact, Quarter 1 (April-May-June) of 2022 was the highest box office in the history of cinema. Only July & August had some underwhelming currents but this is nothing new. It has happened before. This is the DNA of our business. Some films do well, some don’t,” Gianchandani says.

For all the doom and gloom, actors, directors and even fans say it’s hasty to talk of the death of Bollywood. The industry is recovering not only from the pandemic but also from the maelstrom triggered by the death of actor Sushant Singh Rajput. At the same time being challenged by actors and directors from within its rank and file.

Bollywood is ready for change. The tension on sets in Mumbai is tinged with anticipation. Like the city it calls home, Bollywood may be battered and bruised, but is undeterred by these setbacks.

“One must not fret over or rush to write an obituary for Bollywood just yet. The old has to die for the new to be born,” says Bhatt.

(Edited by Neera Majumdar)