The office of Dr Dhaniram Baruah – Assam’s controversial ‘pig heart doctor’ – isn’t just called a clinic. It is called a ‘city’.

Baruah, who was jailed in 1997 after his patient died in a pig heart and lung transplant operation, has spent years trying to get past the notoriety. He is now administering what he calls ‘Baruah biological molecules’ to helpless patients – a “cure” for people with diseases like diabetes, cancer, and even AIDS.

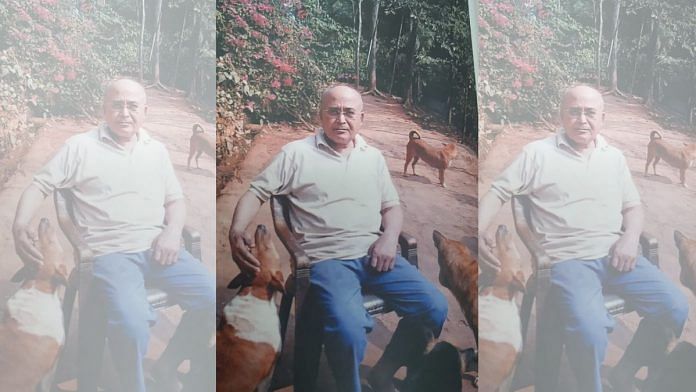

But all that is visible is a bitter, angry man surrounded by dogs. As many as 175 dogs have the run of his ‘city’ in Sonapur. Interestingly, many of these animals are the progeny of those he originally used for his transplant experiments.

About 100 metres off the National Highway 27 that connects Guwahati with Silchar, a rusted sign on a discoloured white wall announces the ‘Dr Dhani Ram Baruah City of Human Genome’. The so-called city is merely a compound with trees and a few concrete houses. A few hundred metres beyond the large green gate, a winding uphill road leads to a decrepit, partially constructed building – the clinic of Dr Dhaniram Baruah. It was on this very plot that a mob burned down his research institute 25 years ago after a man with a pig’s heart died.

‘Scientific pioneer’

In January, Baruah’s name resurfaced, though this time, he was hailed as a ‘pioneer’ of animal-human transplantation after doctors in the United States successfully transplanted a pig heart into a 57-year-old patient. The American man died two months after the surgery in March. Dhaniram’s patient from 1997, Purno Saikia, died after seven days due to infection.

Baruah and two other doctors [Ho Kei-shing and James] were arrested and jailed for over 40 days before being acquitted by the Gauhati High Court, as the Transplantation of Human Organ Act 1994 did not apply to Assam at the time.

Today Dhaniram has all but escaped the shadow of notoriety, but the years have taken their toll on his health. He can only communicate through hand gestures after a brain stroke left him unable to speak. But that hasn’t stopped him from seeing patients. In his rundown ‘city,’ he is still king.

Also Read: Lucknow’s Brownie going home, but Indians are abandoning breed dogs — tied on roads, bridges

Baruah’s biological molecules

Clad in a black suit, bright red tie and a doctor’s white overcoat, Dhaniram Baruah sits behind a large table in his chambers. Four single-door refrigerators in the room are stocked with vials of his “biological molecules” that promise cures for AIDS, diabetes, cancer, and hypertension.

Dalimi Baruah, his research assistant, acts as an interpreter, but at some point, during the three-way conversation, Baruah gets agitated. He starts banging on the table, shouting incomprehensibly until Dalimi intervenes.

Three dogs, who had earlier been let out of the chamber, stand by the door, watching the scene unfold. Outside, a lanky cross-eyed caretaker monitors the three patients in the clinic as they shuffle in and out of the adjacent waiting area.

Baruah communicates with all his patients by thumping on the desk and sometimes nodding or shaking his head. “The doctor indicated that our daughter would be fine by beating the table. He planned to administer 10 injections, each costing Rs 20,000. After one injection she started menstruating again. This was a good sign,” said Prabhat Das, whose 15-year-old daughter, Neha, had been suffering from bone cancer. After consulting specialists at the Tata Memorial Hospital in Mumbai and Apollo Hospital in Chennai, they brought her to Baruah.

But the family’s optimism was short-lived. Three months later, Neha Das passed away.

There are currently 13 people employed at the institute, including researcher Dr Saigeeta Achrekar, who runs a lab on the compound with three PhD students from the North-Eastern Hill University (NEHU).

Also Read: ‘Boyzilian’ wax to Botox, Indian men trade textbook machismo to feel hair- free, handsome

Expensive, unthinkable ‘cures’

The controversial pig surgery left Baruah with “no income”, but he started working on “cures” for chronic heart conditions, diabetes and hypertension using medicinal plants. “We did these experimental studies and extracted isolates (molecules) from the Cinchona plant,” said Achrekar, his long-time research partner. The surgeon and scientist go back 32 years and claim to have come up with a cure for cancer, HIV, and vaccines for diabetes and hypertension.

“We approached IIT-Guwahati, but they didn’t help us, and eventually we went to NEHU, where we were provided with a research facility,” said Achrekar.

Their research marked the birth of ‘Baruah biological molecules.’

Baruah’s past experience and incarceration have no impact on his actions today. From an ‘impossible’ surgery, the doctor has now jumped headfirst into ‘treating’ patients with unthinkable cures. Baruah, in his 2008 book, Unfolding the Mysteries of Human Genetic Sciences in Heart Diseases and Cancer, claims that trials using these molecules were done on 190 patients, but Achrekar admits there were no peer-reviewed studies published.

“We submitted a number of papers to [the peer-reviewed journal] Nature, but they didn’t publish them since we weren’t ready to give the names of the plants,” he said.

The cures are not cheap, but patients, most from Assam, continue to consult Baruah. Many are terminally ill and turn to the doctor as a last resort.

“I have a 62 per cent heart blockage and have spent over Rs 2 lakh on the injections, but my health is much improved,” said 74-year-old Hari Shankar Jha, who consulted the country’s top-heart specialists before turning up at Baruah’s clinic.

However, there is no proof that these injections work. “He’s really a broken man. But he still has a zeal to do so many things,” said Chemplayil Joseph James, who had assisted Baruah on the botched pig heart transplant surgery and was one of the three doctors arrested.

Also Read: Dedicated teams, cost, facilities — why pvt hospitals do over 75% of organ transplants in India

Village boy meets Indira Gandhi

For a doctor who claimed to have Indira Gandhi’s ear, Baruah’s fall from glory was fast and furious. Born in 1948, Dhaniram Baruah hails from Jagial, a small village in Nagaon district of central Assam. “His parents were farmers, and he would study and work on the farm as well,” said his nephew, Pradeep Baruah.

Dhaniram went on to pursue science from a college in Nagaon and got an MBBS degree from Assam Medical College in Dibrugarh. He claims to have always been interested in applied human genetic engineering, which could be used to treat incurable diseases. From Assam, he moved to Dublin in Ireland, where he completed his general surgical training, and between 1978 and 1982, trained across hospitals in Belfast, London and Stockholm. In addition, he was a fellow at the Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons (FRCS) in Glasgow, Scotland.

In his book, Dhaniram says he met with former Prime Minister Indira Gandhi on 19 April 1984, “11:00 am at her office.”

“I came with my family, met her and I had a 45 minutes discussion and Mr Gopi Arora was present during the meeting, who was the special secretary to her,” he wrote. “I insisted upon to start a laboratory for manufacturing heart valves in Assam,” he added.

Baruah said Gandhi advised him against choosing Assam as a base as it was “strategically not feasible” and that she would arrange for him to undertake this research in Mumbai. “Immediately she called Mr P.R. Late for meeting, who was Director General of Technical Development and ordered both of them to provide me all the facilities including the finance (in Mumbai) [sic],” he wrote.

The Baruah Heart Valve Institute and Research Centre Private Limited was set up in Bombay (now Mumbai) in July 1987.

Is there any truth to the accounts of his interaction with Gandhi? “When we met Mrs Gandhi also, she said that he is a great scholar and an expert on these heart valves. But his luck eventually didn’t favour him,” said Hiranya Bora, a veteran Congress leader from Assam.

It was in this city that Dhaniram would meet Saigeeta Achrekar, then a senior scientist at Bhabha Atomic Research Centre. They became inseparable.

Baruah threw all his energy into developing the heart valve: It consisted of zirconium and a component of bovine pericardium, the tough, double-layered membrane which covers the heart of the cattle. He and his wife, Nirala Baruah, applied and received a patent for the ‘bioprosthetic heart valve’ in 1989.

Also Read:What went behind the ‘breakthrough’ pig to human kidney transplant in New York

Back to Assam

Dhaniram Baruah had his heart set on running an institute in his home state. In his book, he claims that while Indira Gandhi had dissuaded him from setting up an institute in Assam, “she had written a personal letter to then Chief Minister [of Assam] Shri Hiteshwar Saikia.”

Baruah reportedly met with Saikia and then state health Minister Bhumidhar Barman on 26 April 1984. However, he claims his plans never reached fruition as doctors [led by then Assam Health Secretary Kamaleswar Bora] ganged up and “threw him out” of Guwahati.

For the most part, doctors in Assam took his claims with a fistful of salt.

In 1991, he delivered a lecture at a seminar organised at Dawka Clinic & Hospital (now GNRC Sixmile Hospital). This was the first time many doctors in Guwahati were coming face-to-face with Dhaniram, whose exploits they had only heard about. “He delivered a talk on the heart valve that he was making in Mumbai. I can say he was a dashing, dynamic man with a lot of dreams,” said Dr Banajit Choudhury, medical consultant at Dispur Hospital.

But the surgeons were not convinced of Baruah’s valve. “I found that he had deficit knowledge on the valve structure of the heart. I asked a question to which he didn’t know the answer. So, he got angry and shouted at me,” said Dr Anil Bharali, former head of department at GNRC Heart Institute in Guwahati. “I was confused as to how he could’ve been trained in Britain given his lack of knowledge.”

However, by 1995, Dhaniram Baruah’s dream came true. He set up ‘Dr Dhani Ram Baruah Heart Institute and Research Centre’ in Sonapur.

By 1996, Baruah claimed he had performed the “first open-heart surgery in the entire north-east.” Saigeeta, who also relocated to Assam, calls it a success, but the medical fraternity and state political leaders did not share the same sentiment.

When he started the heart centre, he did not get any patients, said Kamala Kalita, General Secretary of the Asom Gana Parishad who was health minister at the time. “We don’t know any patients on whom this was done,” he said.

Also Read: Yale researchers make hearts of pigs beat again hours after death. It’s a big deal

The infamous pig heart

Purno Saikia, a farmer from Assam’s Golaghat district who had a ventricular septal defect (hole in the heart), was desperately seeking treatment.

Saikia was a friend of Baruah’s cousin, Dalimi said. It was through this chain of acquaintances that Saikia landed at Dhaniram’s doorstep seeking help.

By then, Baruah, taking a cue from his bioprosthetic heart valve, had begun experimenting with pigs. At the International Conference of Artificial Circulation in Germany in 1995, he presented his paper demonstrating that “pig is the only animal genetically closer to human for experimental purpose and organ transplantation and non-human primates.”

“We had bred 94 pigs and done research on them – only then did he perform the surgery,” said Dalimi. He was convinced that xenotransplantation—the process of transplanting living tissues and organs from one species to another—was Saikia’s only hope for survival.

To stop the human body from rejecting the transplant, Dhaniram came up with an anti-hyperacute rejection therapy—done by removing circulating antibodies from the blood—that he administered to the pig organ.

For the surgery, he roped in Chemplayil Joseph James, a clinical perfusionist who operated a heart-lung machine, and Dr Jonathan Ho Kei-shing, a cardiac surgeon from Chinese University of Hong Kong (at the time only called the Chinese University).

Interestingly, according to a South China Morning Post report, in 1992, Kei-shing had headed a “controversial ox tissue heart valve programme” at the Prince of Wales Hospital in Hong Kong. He adopted the Baruah valve technique that used ox valves harvested in India, but was suspended after six of the 12 patients he operated on died.

“We did the transplantation [on Purno Saikia] on 31 December 1996… I had taken a few South Indian nurses to help with the surgery,” James told ThePrint.

Dalimi added that the surgery lasted 15 hours. “We would rest in between. He operated and transplanted a pig heart, lung and kidney (multiple organ failure),” Dalimi, who assisted Baruah as a nurse, said.

Seven days later, Saikia died after his gall bladder, pancreas and liver got infected. On 9 January 1997, Dhaniram, James and Jonathan were arrested. “Seventy policemen came to arrest me as if I was most wanted terrorist,” notes Dhaniram.

“I was also a budding professional with 5-6 years of experience. My career was thrown into the darkness,” James said. In 2001, he moved to Kuwait where he continued to work as a perfusionist. Dr Jonathan was struck off the Hong Kong medical register and, according to Saigeeta, relocated to the US with his family.

Controversy followed Baruah and the institute for years. In 2009, it was attacked and burned a second time by a mob after two severed heads were found near the institute. At the time, Baruah, who was away for work, called it a conspiracy against the institution.

But none of these experiences or his failing health has come in the way of Baruah’s desire to cure the incurable. And the terminally ill continue to knock on the door of his institute. As the caretaker ushers in the next patient, the yips and howls of the dogs drown out all other noise.

(Edited by Zoya Bhatti)