New Delhi: The communal clash in Sambhal had a clear victim—the Hindus. A report said Hindus are the aggrieved party.

This report wasn’t published in 2024. It’s from 1924 — and its author was Jawaharlal Nehru.

A whole century before Sambhal took centre stage in the national conversation for a communal clash over surveying the origins of the town’s Jama Masjid, it was a cause of great concern for MK Gandhi and the Congress party. So much so that Gandhi sent Nehru to Sambhal to study the incident.

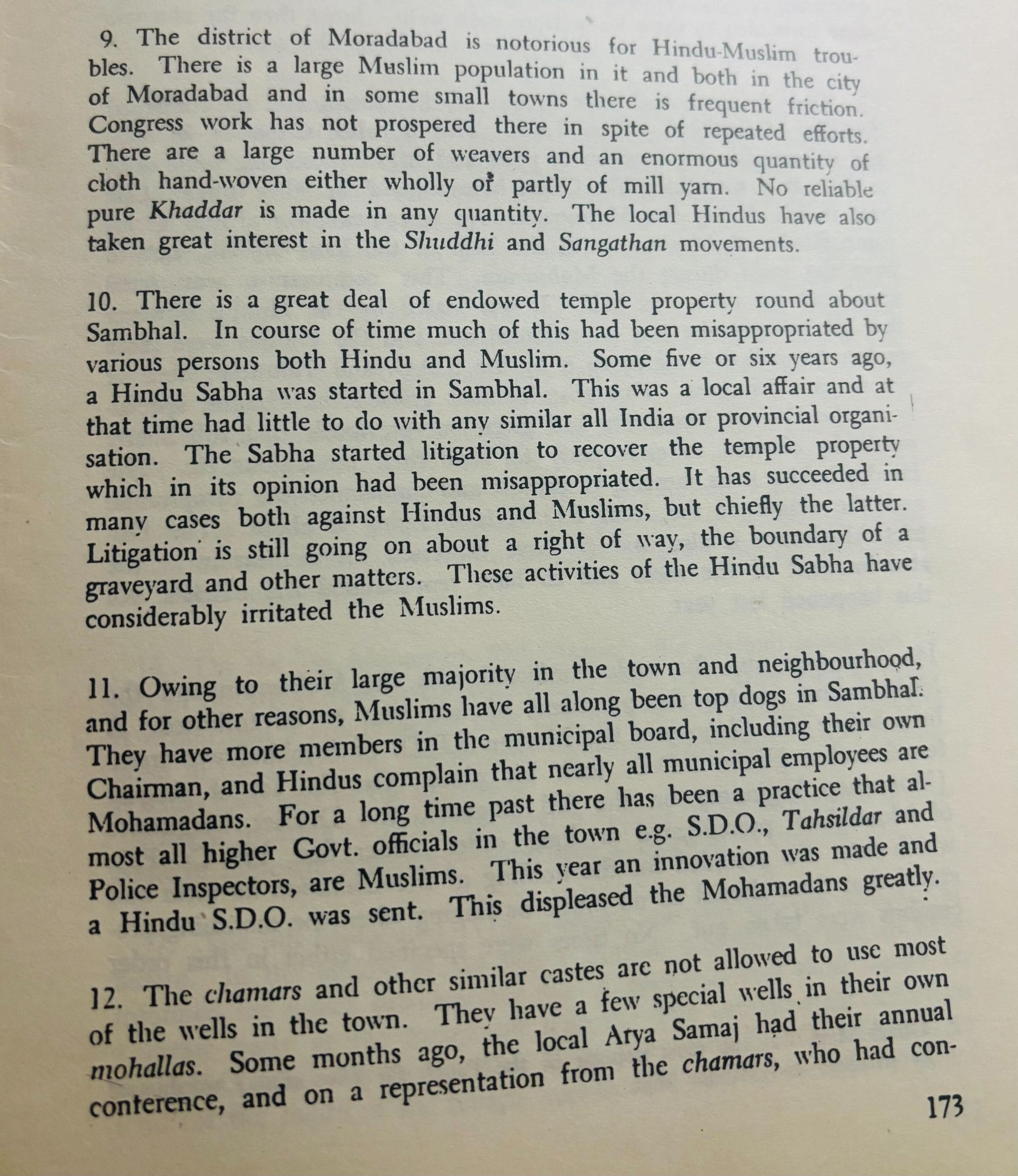

“Owing to their large majority in the town and neighbourhood, and for other reasons, Muslims have all along been top dogs in Sambhal,” Nehru observed in his 13-page report written in September 1924.

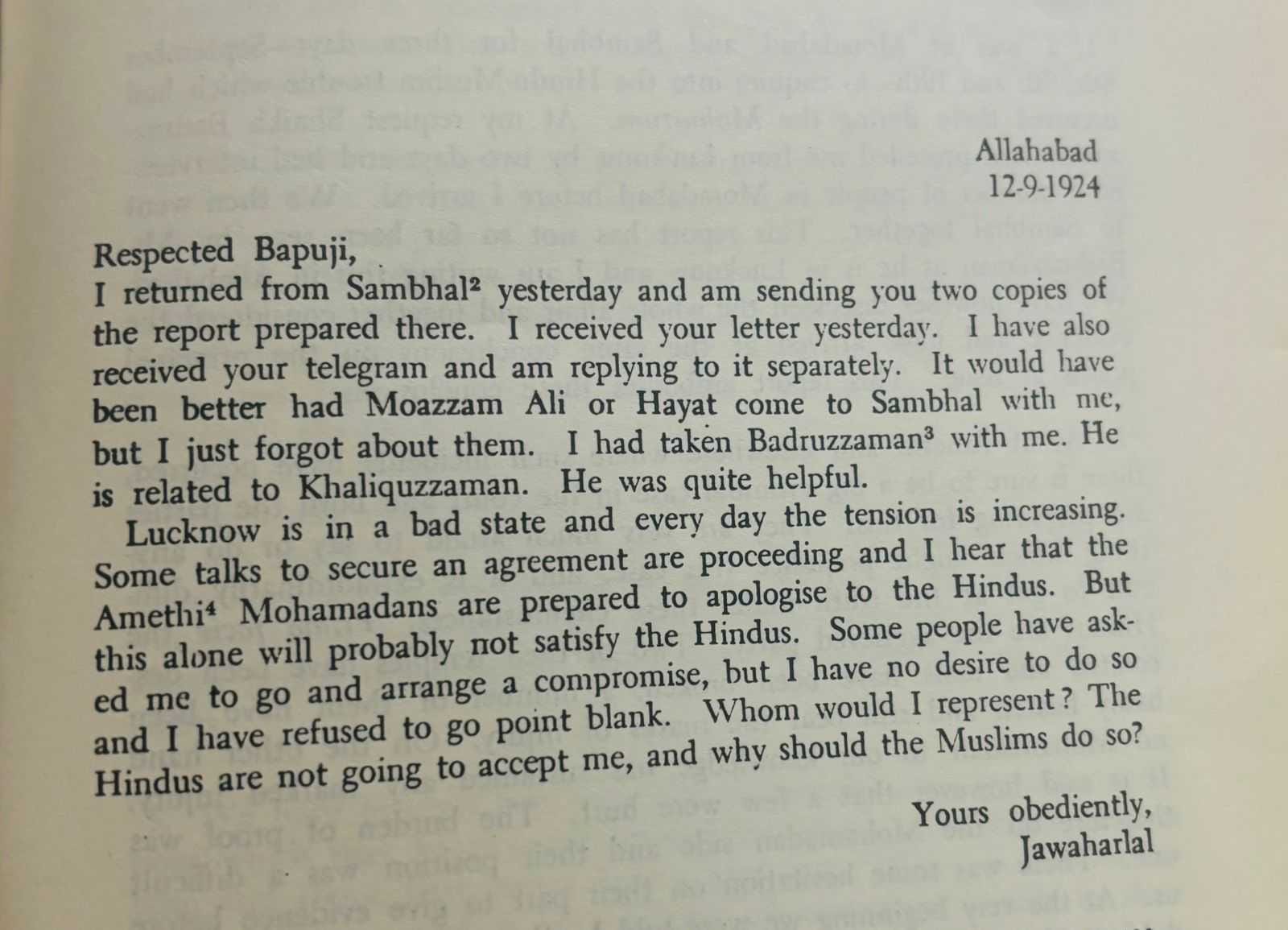

Nehru wrote a short letter to Gandhi, which he sent along with two copies of his report. In the letter, he describes how he was asked to mediate between Hindus and Muslims — and how he said he had no desire to “arrange a compromise”.

“Whom would I represent?” Nehru asked Gandhi in a letter after the visit. “The Hindus are not going to accept me, and why should the Muslims do so? Yours obediently, Jawaharlal.”

Nehru arrived in Sambhal via Lucknow on 8 September 1924, after a group of Hindus and Muslims clashed in the town during Mohurrum, which coincided with an annual fair held in the town. He spent the next three days speaking with Hindus and Muslims at every level — from members of the local administration to shopkeepers to priests and sadhus.

Not much has changed between the Sambhal of 1924 and 2024, according to Nehru’s report. The town was Muslim majority then as it is now. Both Hindu and Muslim communities are on tenterhooks on the eve of every religious commemoration both then and now, afraid that violence would break out. And the Jama Masjid was a bone of contention even then.

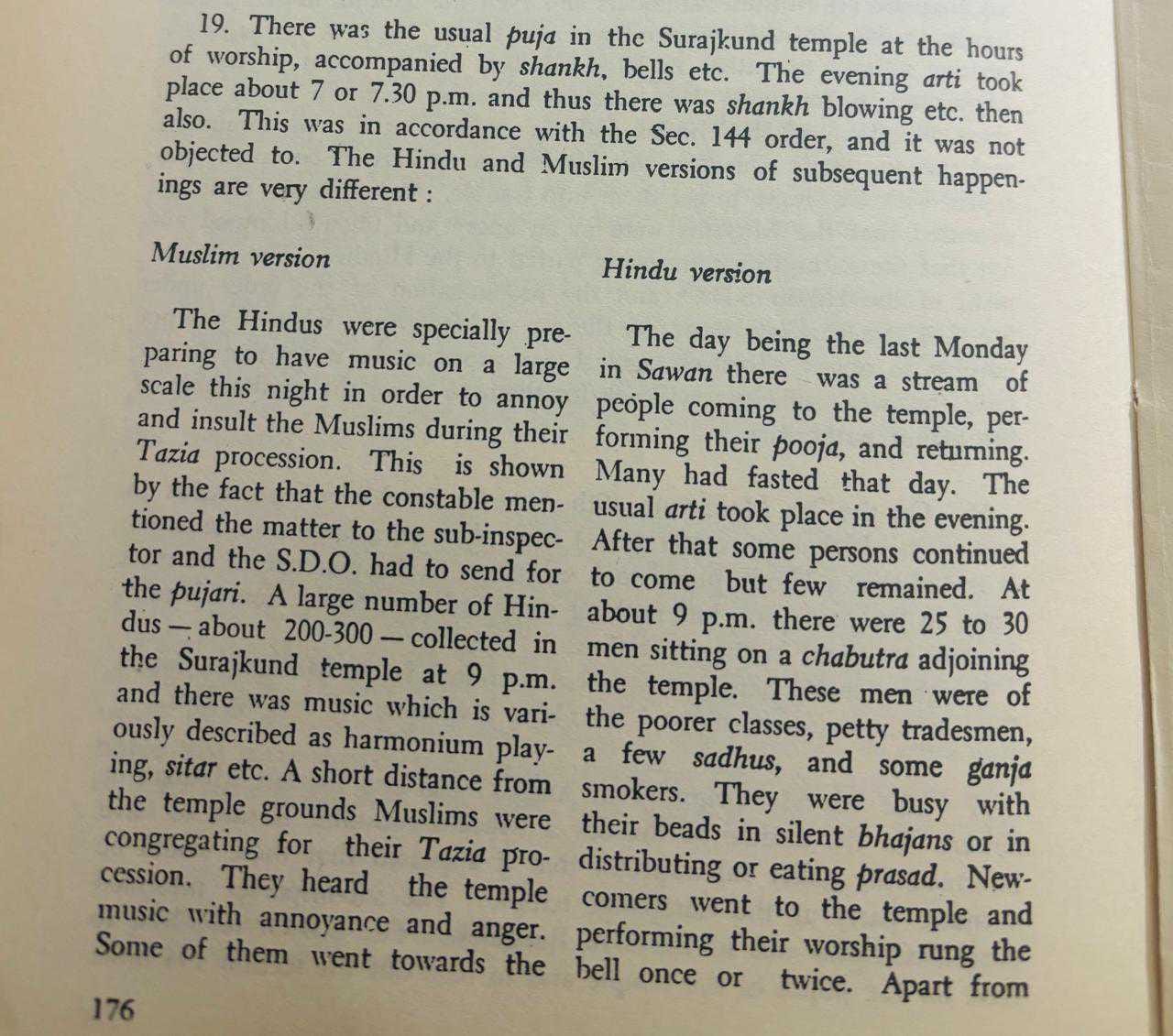

The 13-page report is incredibly detailed, setting the context for the clash that took place. Nehru faithfully reproduces the Muslim version of events side-by-side with the Hindu version, presenting them as comparative columns. The details of the incident are supported by demographic and cultural descriptions of Sambhal and its population, including power dynamics between various communities.

It also gives an insight into the way Nehru approached such conflicts and how he investigated them. In the report, Nehru seems extremely aware of not just his own position in Indian society, but also the precariousness of communal balance in an India that was erupting with all manners of identity crises. It was a time before the idea of Independent India was fully formed.

In his letter to Gandhi, accompanying two copies of the report he’d prepared — written from Anand Bhavan in Allahabad on 12 September 1924 — Nehru briefly describes communal tensions in Lucknow, Amethi and Sambhal. Talks were on to “secure an agreement” between the Hindus and Muslims, and he writes that Muslims are prepared to apologise to the Hindus — but that this alone will not satisfy the Hindus.

The incident in question

The facts of the matter were thus: A local mela conflicted with Mohurrum in Sambhal. In 1923, both communities reached an agreement that the mela would not be held during Mohurrum — but the following year, no such arrangements were made.

On the night of 9 August 1924, a Mohurrum procession took place on a large scale. “Some Hindus as usual took part in the procession,” Nehru notes. But tensions heightened on 11 August, which was the last day of Mohurrum. Many Muslims were upset at music being played and drums being beaten during their period of mourning, and Hindu temples were asked not to play music beyond 9 pm. But tensions broke out over this, and both sides clashed, with violence descending for around two hours. By the end of it, 17 Hindus were hurt and two temples were attacked.

“Prima facie the Hindus are the aggrieved party,” Nehru writes early on in the report. “Two of their temples have been desecrated and idols have been broken; a number of them have been badly beaten and still bear the marks of injury. On the other hand, no Mohamadan to our knowledge has sustained any marked injury. It is said however that a few were hurt.”

Nehru did note that the Hindu side was trying to “improve” upon their version of events by “supplying all manner of details to show premeditation and careful preparation for attack” by the Muslims. They were exaggerating instances of cruelty and improper behaviour by Muslims and also trying to implicate “almost every Mohamadan of note in Sambhal,” as well as local Muslim officials. On the other hand, the Muslims said the Hindus tried to provoke them into an attack.

“The general impression of the evidence is that there was a considerable amount of hard lying on both sides.” The impression he gathered was that of a “courtroom and carefully tutored witnesses repeated a well-prepared story. The two accounts differ materially on almost every important point.”

Also read: Sambhal: A history of violence

Nehru’s observations

Nehru describes Sambhal as perhaps one of the most ancient towns in India — even mentioned in the Puranas. He also writes that “it is said that the next avatar will come from Sambhal.”

While the district of Moradabad, he writes, is “notorious for Hindu-Muslim troubles,” he makes note of how important the town was to both Hindus and Muslims.

He describes the Jama Masjid as a “fine temple” built by Prithvi Raj, and notes that according to modern lore, it “was subsequently converted into the principal mosque of the city.” One hundred years later, this mosque still seems to be the central faultline in Sambhal.

All this context precedes his breakdown of the incident in question, neatly presented side-by-side in two columns. The Hindu version is much longer than the Muslim version, crammed with more facts and details — even a “ganja smoker” is described in this. Earlier on in the report, he writes that Hindus were more forthcoming with their version of events than the Muslims — this is despite the fact that he was accompanied on this fact-finding mission by Shaikh Badruzzaman of Barabanki district, who had left Aligarh University to join the non-cooperation movement in 1920.

The report is scathingly honest, and Nehru is clearly concerned by the depth of religious sentiment forcing people to violence.

“The suggestion in the Muslim version that the Hindus themselves must have desecrated their temples and broken their images is pure fancy and not possible to accept without the strongest proofs,” writes Nehru, describing the suggestion as “absurd.” On that night, Hindus were terrified, writes Nehru — “they all locked and bolted their doors and waited anxiously for the morning.”

Similarly, Nehru dismisses the idea that Muslims premeditated the attack. “But one thing is clear that they were resentful and angry and it may be that they were very ready to accept any real or fancied challenge to them,” he conceded.

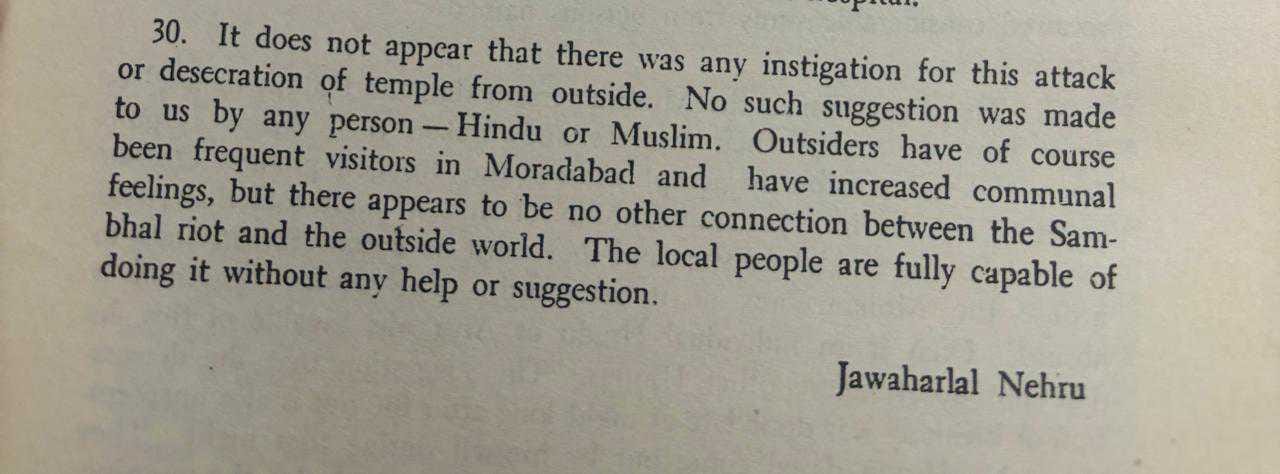

At the end of the meticulous report, Nehru makes his final observations — an opinion on Sambhal that seems to have echoed through the annals of time.

“It does not appear that there was any instigation for this attack or desecration of temple from outside. No such suggestion was made to use by any person — Hindu or Muslim,” writes Nehru bluntly in the concluding paragraph of his report. “Outsiders have of course been frequent visitors in Moradabad and have increased communal feelings, but there appears to be no other connection between the Sambhal riot and the outside world. The local people are fully capable of doing it without any help or suggestion.”

The Sambhal of 1924

Even in 1924, the region had a reputation. Nehru’s descriptions of Sambhal and Moradabad match the belief that the region is a communally sensitive hotspot.

The incident also gives us a glimpse into what religious tensions were like at the time. This particular riot took place a year before the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) was founded in 1925. It was four years after the non-cooperation movement began and two years after the Chauri-Chaura incident.

“The district of Moradabad is notorious for Hindu-Muslim troubles,” Nehru writes. “Congress work has not prospered here in spite of repeated efforts.”

He goes on to mention that a Hindu Sabha had been started in Sambhal around 1919 or 1920 — it was a “local affair” that had little to do with any similar all-India or provincial organisation. But the activities of this Sabha have “considerably irritated the Muslims,” Nehru notes, describing the activities as chiefly including litigation to recover temple properties and negotiating the boundaries of a graveyard.

Casteism, too, was alive and practiced — Nehru observes that the members of the “Chamar” caste were not allowed to use most wells in the town. When someone from the community drew water from a wall, Nehru notes that this upset both higher caste Hindus and Muslims, causing some resentment as it was done during the month of Ramzan.

Nehru sent Gandhi the report on 12 September 1924. On 17 September, Gandhi went on a fast for Hindu-Muslim unity, citing communal violence in Sambhal, Amethi, Kohat, and Gulbarga.

Gandhi’s fast over Sambhal lasted 21 days. As Nehru’s report shows, communal tensions in Sambhal have lasted since.

(Edited by Ratan Priya)

What was the original report of Nehru and what did you caption here? Do you even have a shame? Nehru reported that a Prominent Hindu temple was converted into Masjid and the claims of Mohammadans is wrong. You should use right captions.