New Delhi: One of the most hotly debated topics in contemporary Indian politics, the tangled relationship between Hindi and Urdu, took centrestage at Delhi’s India International Centre. The sister languages, separated by religious lines and later the Line of Control, are undergoing a sort of civil war. But the atmosphere in the hall was not charged or bitter, it was a mix of calm as well as passion.

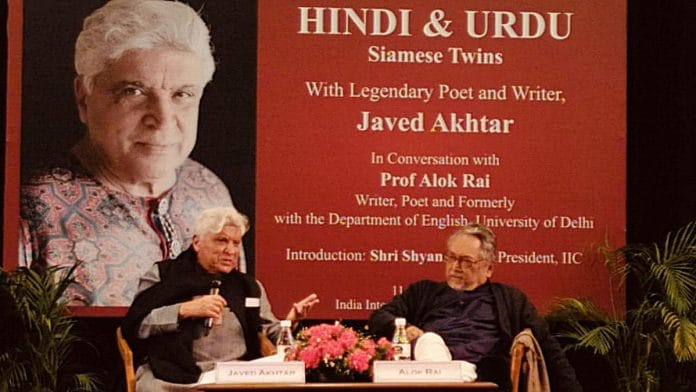

Lyricist Javed Akhtar was in conversation with poet and former Delhi University professor Alok Rai at the IIC’s CD Deshmukh Auditorium last week, in front of an overflowing audience of students, scholars, socialites, and scribes of all ages. Some sat on the floor, others stood, all were completely engaged. An atmosphere of quiet heartbreak prevailed over the fading of a language that most cannot read—a collective loss of heritage— tinged with hope that it can still be preserved.

Akhtar and Rai spoke about Urdu and Hindi with regard and romance. No death knells for Urdu were sounded, nor were there cries about Hindi supremacy. Instead, what everyone was invited to think about was the resurrection of Hindustani, the amalgamation of the best of Urdu and Hindi.

“Imagine the depth of our vocabulary with a dictionary of Hindustani. I suggest the script be Devanagari, because it is the most scientific… It is exact. You pronounce the words the way you write them,” Akhtar said, adding that this suggestion was in no way advocating the erasure of Urdu or the Nastaliq script. “We can even have a dictionary in Roman, but the script doesn’t have alphabets for many sounds we use in our languages,” Akhtar explained.

In his opening remarks, Shyam Saran, the president of India International Centre, said that the talk was one of the most “popular ones” hosted by the IIC, going by the multitude of people who thronged the hall. “The Hindustani language is a part and parcel of Indian culture. Much of our emotional sensibility is tightly associated with the language,” he added.

Akhtar articulated his thoughts with humour and simplicity, not sounding preachy even once. The event lasted for two-and-a-half hours, over double the one-hour schedule, but Akhtar ensured the discussion didn’t die a boring death by making it accessible to the general audience.

Also Read: Urdu’s popularity in Devanagari is a lesson for Muslims—acceptance lies in Indianisation

The myth of a ‘pure’ language

Akhtar likened the search for a ‘pure’ form of Hindi or Urdu to looking for the ‘true’ onion while peeling its layers. “Chhilka hi toh pyaaz hai! (The layers are the onion). By trying to find a ‘pure’ language, you’ll damage Hindi as well. Foreign influences are not wrong. That’s how languages are developed,” he said.

The lyricist also rejected the idea that languages can be divided on religious lines. “Languages are regional, not religious,” Akhtar said, refuting the notion that Urdu is a language of the Muslims.

He reminded the audience that when the Quran’s first Urdu translation was published in 1798, the Muslim clergy were far from pleased. Instead, they were dismayed that the holy book was presented in a language of debauchery—one full of poetry on romance and alcohol. He further noted that the seeds of division in Urdu and Hindi were sown by the British establishment as part of their divide and rule policy.

“There are only two languages, one of the hukumat (government) and the other of the awaam (public). And the hukumat wanted to attack the language of the awaam by sowing seeds of enmity, something the British were good at,” Akhtar said.

Also Read: Sheikh Abdullah embodies early nation-building crisis, and of how little power Nehru had

Truth in absurdity

Having spent his life mastering the art of connecting with audiences through his words, Akhtar knew how to intimately acquaint himself with a room full of strangers while sitting far away on a stage.

Even with a sensitive topic at hand, the mood of the night was light and filled with laughter. Akhtar’s absurdist take on the Urdu-Hindi tussle, communicated with sarcasm and humour, was both illuminating and amusing.

At one point, Akhtar brandished a list of 383 Urdu words that the Delhi Police had recommended substituting with Hindi or English words while writing police complaints. “Of course, the British did nothing here (in India) that should make us despise them,” he said sarcastically of the police dictum.

“Police advise against the use of the word ‘zakhm’ and to use ‘chot’ (for injury). But is this an exact translation? Zakhm sounds more serious! The perpetrator will get away!” Akhtar said.

He also pointed out instances where the Delhi Police couldn’t find exact translations. “The police have advised against the use of the word mushtaba (accused), and asked people to write ‘jispe apraadh karne ka shaq ho’ (the person under suspicion of committing a crime). Never mind that shaq (suspicion) is an Urdu word!”

Akhtar warned that imprecise language could have serious consequences. “The problem is these statements will go to court. This will change the meaning of the case a person is trying to build,” he said.

Echoing these sentiments, Rai said that the development of an intertwined language like Hindustani is an “achievement of our civilisation” and that the attempted erasure of Urdu by calling it a “foreign language” is “a gross misunderstanding at best”. Akhtar and Rai both affirmed Urdu’s status as a language of the subcontinent.

“Along with neglect of Urdu, there’s also an enormous longing for it. Why? Because it is a distillation of what’s finest about my civilisation. Eloquence is disappearing from public life, but the hunger for it is still there,” Rai said, while answering a question on the neglect of Urdu.

Akhtar and Rai discussed how Urdu poetry, in particular, has shaped how young Indians express love, longing, pining, and intimacy. The tragedy of the sibling languages’ separation was woven into a romantic narrative, a feat only an Urdu poet of Akhtar’s calibre could pull off.

(Edited by Asavari Singh)