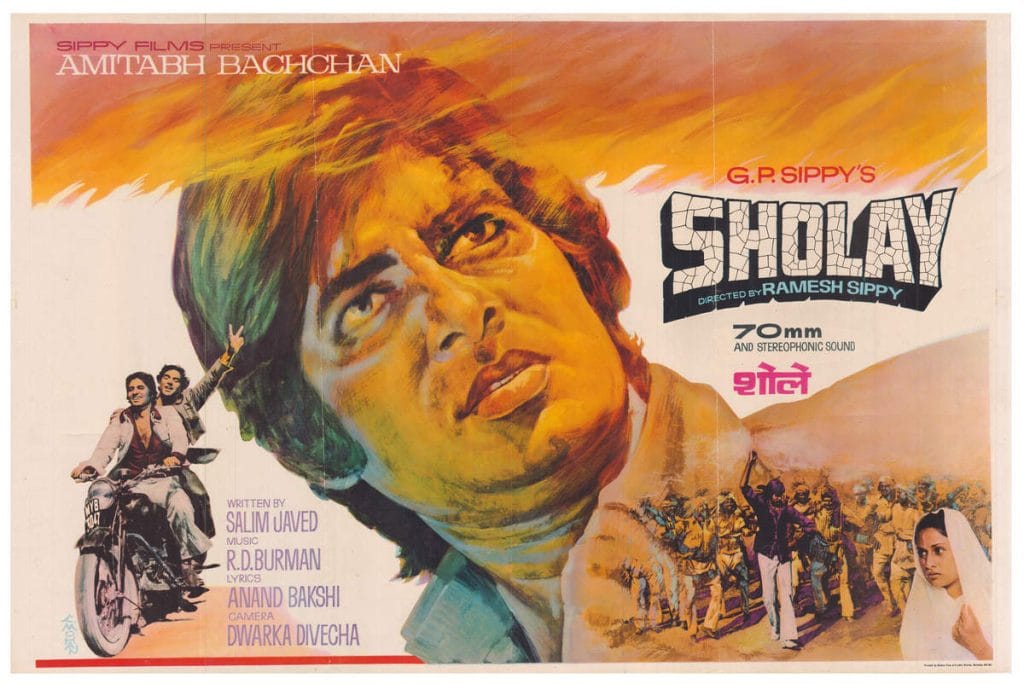

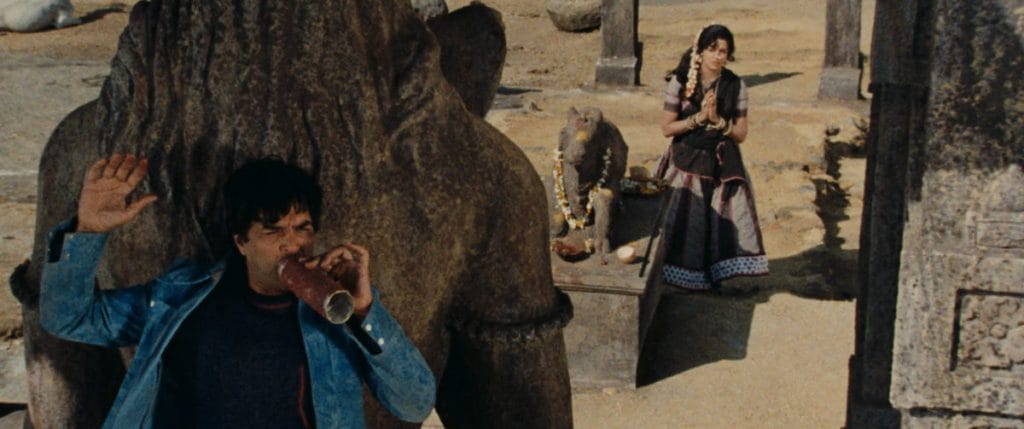

New Delhi: Ramesh Sippy’s Sholay established itself as an emotion in India, but it also became a much-loved film across the globe from Iran to Russia and even China. It’s the classic ‘curry Western’ with friendship, revenge, and romance. And this year, on its 50th anniversary, Gabbar Singh’s villainy, Thakur’s resilience, and the goofy antics of Jai and Veeru are gracing big screens again from Italy to Canada.

It made its European debut this year with a screening in Bologna, Italy, and is slated for its “North American premiere” at the 50th Toronto International Film Festival (TIFF) on 6 September at the 1,800-seater Roy Thomson Hall.

“Riffing off Sergio Leone’s spaghetti westerns, Akira Kurosawa’s Samurai films, and classic westerns, the film follows two ne’er-do-wells asked to rid a village of a notorious bandit,” reads the description of the film on the festival’s official website.

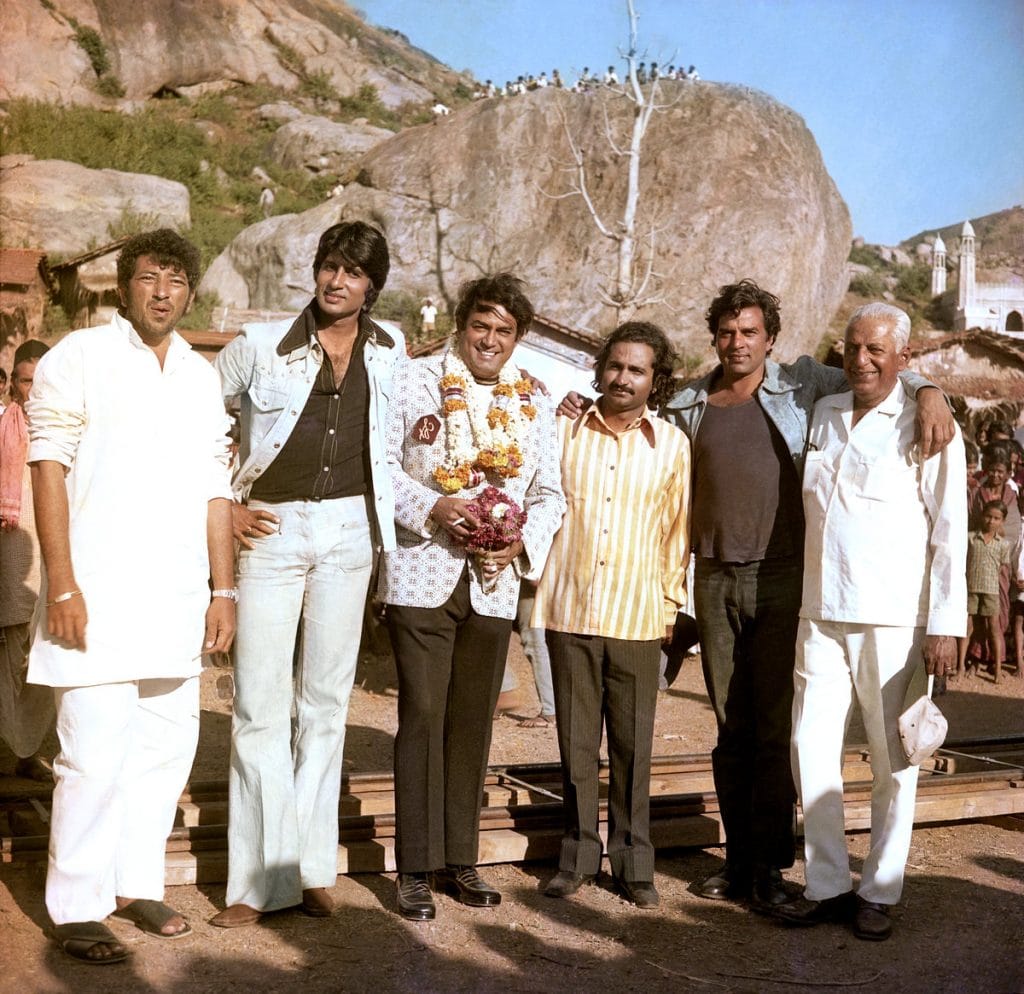

In the run-up to Sholay’s 50th birthday on 15 August, Gabbar Singh (Amjad Khan), Thakur (Sanjeev Kumar), Jai (Amitabh Bachchan), and Veeru (Dharmendra) have already had a warm reception in Italy. Sholay’s renewed global tour began on 27 June with the world premiere of its restored version at the Il Cinema Ritrovato Festival in Bologna. Nearly 2,000 people gathered in Piazza Maggiore for the open-air screening, cheering as the three-hour-twenty-four-minute film ended at 1:30 am on a warm summer night, according to Shivendra Singh Dungarpur, founder-director of the Film Heritage Foundation, which restored the film.

The film’s enduring success has been the subject of scholarly pieces and newspaper reports.

“Sholay is, in fact, the Indian film industry’s textbook. The film married a potentially B-grade genre narrative to the big budget of a mainstream extravaganza, and taught the industry how formula can beget a classic,” wrote author and film critic Anupama Chopra in her book Sholay: The Making of a Classic.

Also Read: In Sholay year, Amitabh Bachchan acted in an Assamese film. It never got released

The soft power of Sholay

Sholay’s world dominion started in 1975 and never really ended. To mark its 50th anniversary, an Iranian newspaper devoted an entire page to the film. The piece emphasised the central theme — the unbreakable friendship between outlaws Jai and Veeru and the epic villainy of Gabbar Singh, known popularly in Iran as ‘Jabbar’ Singh.

???? On #Sholay’s 50th anniversary, #IranNewspaper dedicated a full-page tribute to the iconic film.

With its unforgettable story of friendship, Sholay became a cornerstone of cinematic memory in #Iran; so much so that many Iranians still associate #Bollywood with this epic. pic.twitter.com/xNoNPd4JUw

— Consulate General of the I.R. Iran in Mumbai (@IRANinMumbai) July 16, 2025

“Sholay’s success in Iran is a throwback to a time when global culture was less homogenised and less Westernised. The pockets of popularity of Hindi cinema were possible because distribution outlets had not been taken over—in some cases nationalised and in other cases Westernised,” said Kaveree Bamzai, senior journalist and former editor of India Today.

The Indo-Iranian cinematic connection, however, dates back much earlier. Before the 1979 Iranian (or Islamic) Revolution that ended the Pahlavi dynasty under Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, Indian films were extremely popular in the country. Raj Kapoor was the heartthrob. His Shree 420 (1955) and Sangam (1964) reportedly enchanted audiences with their emotional storytelling and exotic European locales.

Both films were dubbed into Persian and distributed by SP Hinduja, who also took Sholay to Iran. By the time it arrived, Iranian audiences were already familiar with the faces of Amitabh Bachchan, Dharmendra, and Hema Malini. It ran for a whole year in Tehran’s Aasiya Theatre in the 1970s, Bamzai told ThePrint.

The popularity of Hindi cinema in Iran also created the term ‘Hindibaazi’, which referred to the melodrama in Bollywood films.

Its impact was so far-reaching that Amjad Khan’s portrayal even inspired Iranian actor Navid Mohammadzadeh to mimic his looks and mannerisms in a role.

“Bollywood films, including Sholay, lent themselves to the language of Iranian cinema, known as ‘film Farsi’. The term itself suggests that it is reliant on melodramatic, escapist cinema and a lack of in-depth aesthetic elements, which were features of Bollywood films,” said Dr Swapnil Rai, media studies professor at the University of Michigan and author of Networked Bollywood: How Star Power Globalized Hindi Cinema.

That is why Sholay still occupies a prominent position in a country whose cinematic greats include Abbas Kiarostami, Majid Majidi, Asghar Farhadi, and Ali Hatami.

In the then Soviet Union, both endings of Sholay were shown in its theatres in 1979. The film caused mass hysteria of sorts, with newborn twins named Jai and Veeru, and people working out the date when Holi was celebrated in India.

It was also released in China in 1988 in two parts, dubbed in Mandarin by the Shanghai Film Dubbing Studio. It set the record for the highest-grossing Indian film in the country for decades, only surpassed in 2017 by SS Rajamouli’s Baahubali: Part 2.

In neighbouring Pakistan, Indian films were banned after the 1965 war. Sholay only reached Pakistani theatres on 27 April 2015, almost 40 years after its original release. It did better business than the 2002 release Devdas, which until then had been a mega hit, starring Shah Rukh Khan, who is extremely popular in the country.

Spaghetti to curry westerns

Sholay took its cues from Sergio Leone’s spaghetti Westerns, with brooding silences, stylised shootouts, and intense close-ups straight out of Hollywood. The massacre of Thakur Baldev Singh’s family echoes the annihilation of the McBain family in Once Upon a Time in the West (1968).

If Sholay borrowed the flavour of a spaghetti Western, its own ‘curry Western’ DNA ended up seasoning films far beyond India.

Amitabh Bachchan, who after Sholay and a run of subsequent hits had become a global star like Raj Kapoor, found fans from Pashto and Dari-speaking communities in remote Afghanistan to audiences in Egypt’s cities and provinces. In Shahrbanoo Sadat’s Parwareshgah (The Orphanage), a 2019 Danish-Afghan film, there are multiple nods to characters played by the veteran actor.

“It was not surprising that people had an appetite for popular cinema and melodramatic delivery and dance and song, that was fundamentally immersed in moral messaging,” said Rai.

In one scene, the protagonist Qodrat (Qodratollah Qadiri) copes with the harrowing shock of a friend’s accidental death by a hand grenade by reminiscing about the song ‘Yeh Dosti’ from Sholay.

In Bangladesh, it was remade as Dost-Dushman (Friend and Enemy). The 1977 film copied Sholay frame-by-frame but did not credit the original.

Also Read: Amitabh Bachchan shares Rs 20 Sholay ticket from 1975. ‘Price of a soft drink nowadays’

Rebirth of a classic

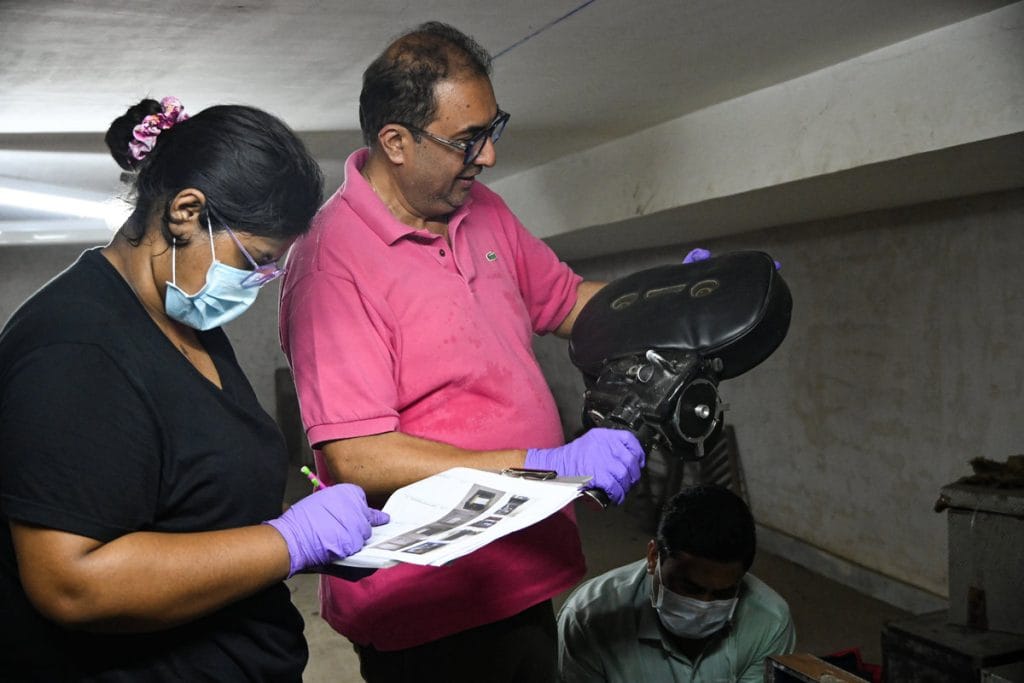

While Sholay has played in theatres around the world, the new push for global screenings is driven by its painstaking restoration by the Film Heritage Foundation. The process started in 2022, when Shehzad Sippy of Sippy Films initiated discussions on reviving the classic.

Unlabelled cans containing the 35mm camera and sound negatives were found in a Mumbai warehouse, while the original magnetic sound elements were fished out from the Sippy Films office, according to a release from the foundation. Additional reels in the UK were sourced with help from the British Film Institute. These were then carefully shipped to L’Immagine Ritrovata in Bologna, one of the world’s leading film restoration facilities.

It was not all smooth sailing from there. The three-year restoration faced its biggest challenge in the deterioration of the original camera negatives. With those no longer viable, the team used interpositives located in London and Mumbai. The foundation even tracked down the original Arri 2C camera used to shoot the film. But with 70mm prints no longer in use, they turned to veteran cinematographer Kamlakar Rao.

Rao, who had collaborated on Sholay with its cinematographer Dwarka Divecha, brought vital knowledge of a trick Divecha used: placing a ground glass in front of the camera lens and marking it to delineate the margins of the 70mm frame. That insight allowed restorers to work in a 2.2:1 aspect ratio.

The result is a rebirth of the classic. It’s a chance for the world to experience a cultural phenomenon, this time in high definition and with every gunshot, glare, and Gabbar punchline even sharper than it was 50 years ago.

(Edited by Asavari Singh)