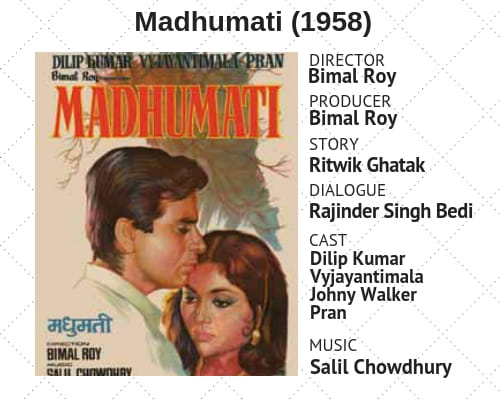

In Bimal Roy’s storied career, the one film that has stood as an outlier is the Gothic noir mystery Madhumati (1958). Written by another master, Ritwik Ghatak, this Dilip Kumar-Vyjayantimala starrer has informed pretty much every reincarnation saga that came after — from Chetan Anand’s Kudrat (1981) to Farah Khan’s Om Shanti Om (2007).

Of the many things that Madhumati got right, Pran’s antagonistic turn was one. The legendary actor’s 99th birth anniversary was celebrated this week.

Of the many things that Madhumati got right, Pran’s antagonistic turn was one. The legendary actor’s 99th birth anniversary was celebrated this week.

In the guise of a noir thriller, Madhumati is actually a tale of unfulfilled love. It’s also an allegory for the consequences of encroachment — of capitalism in the land of tribals and of men into women’s spaces.

Also read: Do Bigha Zamin, the Bimal Roy classic that Bollywood should look at now more than ever

Cinematographer Dilip Gupta builds the ‘mood’ for the thriller, a must especially for black and white noirs, from the first rain-drenched frames. Escaping a storm and a landslide on the way to pick up his wife and child, Devinder (Dilip Kumar), an engineer, takes shelter in a mansion on a mountain by the riverside with his friend (Rehman). At the dilapidated mansion, some ‘happenings’ in the dead of the night lead Devinder to a painting of the former owner of the place, Raja Ugra Narayan (Pran).

Suddenly Devinder starts seeing images and we cut to a flashback — a cinematic device that has been a favourite with filmmakers in the horror mystery genre.

In his previous life, he was Anand, an accountant at Ugra Narayan’s Shyamgarh timber estate. It was here that he met Madhumati, a tribal village belle.

When Anand first sees her, she’s standing atop a far-off mountain, shrouded in fog — an enduring directorial style.

With Anand and Madhumati falling in love over several songs, Ugra Narayan lays his eyes on the tribal girl and keeps looking for ways to trap her.

On one occasion, he manages to send Anand away, tricks her to come to his mansion and attempts to rape her. On the rainy chandelier-lit night, shadows loom large and appear overpowering.

Also read: Pran, the most popular Bollywood villain who often carried more weight than the hero

Anand returns to the village to find Madhumati missing and begins the search for clues to the mystery behind her vanishing.

If you have seen enough reincarnation-based Hindi films, many of which owe their existence in some manner to Madhumati, you know where this story is going.

The beauty of Roy’s film lies in its ambience and the exquisite black and white frames. The miniature shots of the mansion are a joy to behold for thriller fans, especially in a country that hasn’t made enough genre films. The haunting melody of ‘Aa ja re’, the archetypal ghost song, elevates the narrative.

Salil Chowdhury’s 11-song album, penned by lyricist Shailendra, adds to the film’s lure with folk-inspired compositions. Given its tribal setting, songs like ‘Suhana Safar’ and ‘Julmi Sang Aankh Ladi’ add to the charm of the idyllic life. They work as standalone pieces too — ask any Hindi film lover going to the mountains!

Funnily enough, Chowdhury’s involvement in the film was opposed by the distributors of the film as well as Dilip Kumar because the composer wasn’t considered a hit maker, Roy’s daughter Rinki Roy Bhattacharya wrote in the book Bimal Roy’s Madhumati: Untold Stories from Behind the Scenes.

It is said that the commercial failure of Devdas (1955) pushed Roy to make a safer mainstream film with the same cast. And Ghatak came to his rescue with a layered story that Roy mostly shot on location, which added to its mystique.

Also read: Superstar Dilip Kumar was the ‘Thug of Hindostan’ in 1968 hit film Sunghursh

The reincarnation of lovers separated due to a tragedy is a trope that Kamal Amrohi’s Mahal (1949) introduced in Indian films. But Madhumati shaped it in a way that it became entirely its own.

The biggest strength of Madhumati was the aching “ambivalence” it offered in the treatment of the story’s resolution, as Bhattacharya wrote in Bimal Roy: The Man Who Spoke In Pictures — again, a rich directorial touch that later filmmakers like Khan just couldn’t replicate.

Modern Hindi cinema seems far too removed from conventional themes like reincarnation. But in a world where lovers have stopped reuniting on screen in afterlife, the existence of Madhumati becomes even more enchanting.