Bengaluru: “You get a dosa, you get a dosa – everybody gets a dosa!” Last weekend, Bengaluru-based heritage tour leader Dhiren Kanted recreated a humbler version of Oprah Winfrey’s iconic “you get a car” moment. But instead of cars, he gave away plates of the popular South Indian dish to the four people who had joined the food walk called ‘Death by Dosa’.

It’s an unlikely combo of history plus food plus exercise. And only a city like Bengaluru can do it justice.

The three-and-half-hour tour combined dosa with the history of one of Bengaluru’s oldest neighbourhoods, Chickpet. Conducted by a boutique experiential tour company, Gully Tours, which was set up in 2009, Death by Dosa is one of the most popular walks in the city.

It’s a natural evolution of the older ‘Pete Walk’ that has one dosa stop and is now conducted for foreigners. Its name inspired by the famous dessert ‘Death by Chocolate’, the dosa walk was first conducted in 2021. It was customised for Bangaloreans and people from other parts of India with the inclusion of two more dosa joints. And Kanted introduces them with all the flair of a magician about to reveal his secrets.

“I want you to be open to the different things that are happening around you. There are a lot of sensory things you can feel as you walk through the alleys, the shops and neighbourhoods,” he says, before entering a narrow lane teeming with people even though the clock hasn’t struck 9 am.

The tour is packed with sensory overload as participants are taken to three historic dosa spots within the tiny bylanes of Bengaluru’s old trading quarter.

Crispy, thin golden-brown dosas laden with ghee materialise in a flash as Kanted stops at one of the barebone eateries in the lane. Each morsel carries the unmistakable whiff of mustard seeds and curry leaves. Mini masala dosas at a refurbished joint dating back to the 1960s are the first on the menu. The savoury dish is paired with potato gravy and rich coconut chutney. Next is the famous pudi masala dosa, a ghee-infused marvel oozing with potato and creamy chutney. A gastronomic gem, it’s served on an ordinary paper plate. The culinary adventure culminates at a food joint so cramped there’s hardly any place to stand. But that doesn’t stop dosa junkies from standing on the road to devour khali dosa – a thick, fluffy counterpart to the classic variant.

The simple dish belies the complexity of flavour it can deliver.

“The combination of what goes in and around a dosa makes for an orchestra in your mouth. There’s a type of dosa for everyone, that’s what makes it so special,” says Kanted.

Away from the sleeker and cleaner parts of the bustling megalopolis lined with glass-facade buildings and minimalist-design cafes, Chickpet overflows with stores and buildings fighting against the passage of time. The saree mills, gold jewellery, and retail shops lining the streets are reminiscent of an era before Bengaluru became India’s Silicon Valley and start-up hub.

“Chickpet area was conceived by Kempe Gowda, who was one of the ministers in the Vijayanagara empire. He was the first person who came and settled in the area and set up the commerce in the 1500s,” Kanted gives a brief introduction to a group standing in front of a crowded coffee truck operated by Karnataka Coffee Board. The attendees, mostly men, have come for their regular dose of filter coffee after their morning walk.

Kanted continues his quick historical summary of the neighbourhood.

“In the 1700s, you had the Mughal emperors here, then colonialism, and so on. So, it’s a meeting of different cultures. And there are a lot of dosas here,” he says.

Dosa, morality, and real estate

Chickpet is a maze of narrow alleys where sunrays struggle to reach. Kanted explains that the presence of so many food outlets in the neighbourhood is due to its commercial nature.

“These are places where one can come and have a hearty meal at a budget price. These shops are also called ‘tiffin’ because they serve quick meals, or you can get a takeaway,” says Kanted.

The three eateries included in the tour were – Chikkanna Tiffin Room (CTR), Lakshmi Nataraj Tiffins (LNR), and Druti Tiffin Room (DTR). Khali dosa, the cheapest on the menu, was priced at Rs 40, and the most expensive plate, pudi masala dosa, cost Rs 110.

The conversation naturally revolves around dosa but occasionally drifts to real estate. In their 20s and 30s, the attendees gather in front of a decrepit colonial-era wooden structure called Mohan Building. A tour around the building’s unused first floor is a part of the itinerary, but the group runs out of luck — the security guard doesn’t have the keys. While they gaze at the fabric and clothing stores on the ground floor, money talk briefly takes precedence over food.

“The interesting thing is that more than the rent of a shop is the goodwill value of getting the spot. So, you might be paying Rs 40,000-50,000 monthly rent, but the goodwill amount to get the shop might be Rs 50-60 lakh here,” Kanted says.

Inside LNR–the biggest of the three eateries–are two boards with instructions in Kannada for parents and children.

“You see those boards there, they mention the importance of parent-child relationships. Basically, it is saying children shouldn’t abandon their parents,” Kanted summarises the messages written in Kannada. The signage and no-frills service remind a participant of the Irani cafes in Mumbai. “These messages are like those ‘don’t talk’ and ‘be silent’ messages at the Irani cafes,” they say.

Tip of the iceberg

The sizzle of dosa batter hitting seasoned flat pans follows the pedestrians everywhere, the aroma of chutneys and spices tantalise and tease. Over generations, these ‘tiffin’ eateries have cracked the formula of delivering consistent taste without compromising on speed.

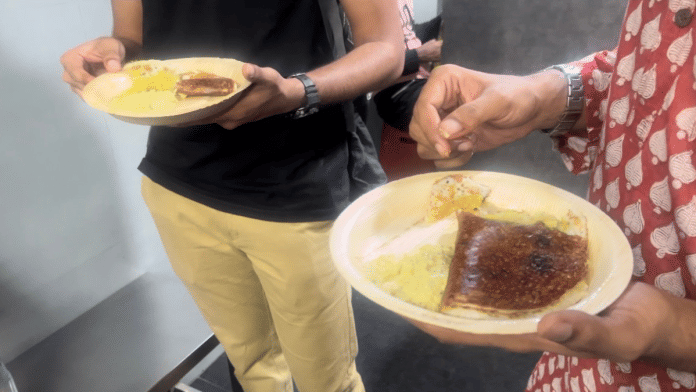

In one open kitchen, the cook tends to four dosas on a massive pan, anointing them with ghee like a priest doling out benedictions. The cooked dosas are swiftly plated and then catapulted over the counter to four participants in the walk. Each of the four people reviews the texture and taste of the dosa and chutney.

“We are deconstructing the dosa today,” one of the participants says. She likes to keep the masala stuffing aside, take a bit of the plain dosa and mix a bit of masala. The other participants cheer her on—“Break the system,” says one person with a grin. There’s no judgement. “Hack the system,” says another.

According to Kanted, the different dosas that are available in these eateries are still just the “tip of the iceberg”.

“Dosa at this point is just a carrier,” he says. “There can be different permutations and combinations,” quips another participant.

But the dosa isn’t the only hero of the day. A few people in the group are also chutney supremacists.

“Chutney has to be great, sambhar is secondary. If the chutney is not good, it’s a no for me,” one guy says.

There is no room for watery chutney without a potent hit. “If I am looking for a dosa place, I look at the photos — not of the dosa but the chutney,” another chutney snob declares. “Chutney has to be thick, you should feel the (taste of) coconut.”

Kanted, who is a scientist by day involved in producing and purifying proteins, conducts these walks to indulge in his love for history and food. His association with Gully Tours began at the start of 2024—he was selected from a pool of 20 people after a six-week workshop on conducting heritage walks.

“Dosa, in essence, is one of those things that’s a comfort food for most people living here. It’s something you won’t be bored of because of the variety,” says Kanted.

But he steers clear from the origin of this savoury crepe made from a batter of fermented ground white gram and rice. Both Karnataka and Tamil Nadu lay claim to this dish, which goes back at least 2,000 years.

The last four months have allowed Kanted to get a sense of the participants who join the dosa trail. It’s a combination of interest – for some it’s the dosa, and for others, it’s the history of Chickpet itself. He recalls one guest, an Indian from Colorado, who joined the tour because he managed an eating joint in the United States and wanted to research more about various dosas.

One of the participants who had signed up for the walk that weekend was Pranav Bhosle, a software engineer in his 20s. Originally a Mumbaiker, he has been living in the city for two years. It was the long election weekend that finally allowed him to join the food walk.

“Whenever I eat dosa, I keep hearing that Rameshwaram (a famous food chain) is overrated, there are better spots in Bengaluru you can go to. So I thought maybe this will help me find those spots,” he says. In March, a bomb went off around lunchtime at the Whitefield outlet of Rameshwaram Cafe, injuring nine people.

The food walk made Bhonsle realise that the dosas he had been eating in the Bellandur area were subpar.

“The batter is a little over fermented. The dosas are more sour. But everything I ate today was so fresh,” he says. “It had amazing texture, every dosa was different in its own way.”

His time in Bengaluru has converted him into a dosa fiend—he can have it for breakfast, lunch and midnight snack. It’s the ultimate comfort food.

But there is a limit to the amount of dosa a person can eat in three hours. By the end of the tour, the participants struggle to finish the third one — a soft and spongy khali dosa. A few surrendered in despair, their stomachs and palates defeated—temporarily.

“But it doesn’t get saturated. It keeps growing. I think the love for dosa keeps them coming back. So, Death by Dosa will metaphorically happen for that day because you will be satisfied,” he says.

(Edited by Humra Laeeq)