Nagaon, Assam: On a December afternoon in Assam’s Nagaon, the lane where people once queued for movie tickets filled up with the blaring sound of machines. By evening, the outer walls of Krishna Talkies at Bengalipatty lay in pieces. The demolition, carried out on 5 December last year, drew little attention as it proceeded quietly without any warning or announcement. As the day came to an end, a cinema hall that had shaped the cinema-going culture for nearly eight decades disappeared, leaving only the rubble behind.

Nearly 120 km from Guwahati, Krishna Talkies, built by Kashi Prasad Bihani, was once considered to be the cultural hub of Nagaon. People travelled in buses and bullock carts to watch their favourites.

“People would even stay back till morning after late screenings,” recalled Tapan Saha, who has been running a paan shop around the premises since 1964. The films ranged from Assamese landmarks such as Ronga Police (1958) and Dr Bezbarua (1969) to Hindi hits like Phool Aur Patthar (1966) and Talash (1969). Even dubbed films, such as Rajshri Productions’ Bhagya (1967), the Assamese version of Taqdeer (1983), drew packed houses.

The hall itself evolved with the town. Originally set up near the Bengali Pujabari area before the 1950s, it moved to Bengalipatty and grew from a bamboo-and-wood structure into a sprawling two-storey cinema. With seating for 959, subtle Art Deco flourishes, and Assamese motifs like the japi carved onto the auditorium walls, Krishna Talkies was larger and more ambitious than most of its contemporaries.

The fall of Krishna Talkies mirrors the structural collapse of single-screen cinemas across Assam — and much of India — driven by a lethal mix of violence, neglect, policy apathy, and changing economics. In the late 1990s and early 2000s, militant bans on Hindi films and bomb attacks inside halls hollowed out audience confidence. But when peace returned, the crowds did not. A 2006 survey by the Assam Institute of Management, commissioned by Nitin Bihani, found that the sharper deterrent was not ideology but infrastructure: decaying halls, poor maintenance, and an unwillingness or inability to modernise.

Digital conversion came late and unevenly. Although Krishna Talkies upgraded to the latest digital projection system by 2008, it was only in 2016 that they had installed push-back seats and air-conditioning systems in the balcony. The lower stalls remained the same. But this modernisation came at a cost. Ticket prices rose from annas and rupees to Rs 200-Rs 300, pushing out the very audience that regional cinema historically relied on.

“Cinema was once for the poor,” said Saha, who has now relocated his shop outside the premises. “Now we can’t afford the cost.”

For years, Krishna Talkies limped on, buoyed occasionally by big releases, until the coronavirus pandemic dealt a final blow to its fragile finances. OTT platforms then finished what years of attrition had begun. Recent monthly losses touched Rs 2 lakh, according to hall manager Bishnu Bora.

“There was no way out,” he said.

The last films — Jaat and Raid 2 — screened in May 2025 passed unceremoniously. The hall never got to show 2025 Assamese blockbusters like Bhaimon Da or Zubeen Garg’s last film Roi Roi Binale. In July, Guwahati’s Apsara Cinema followed Krishna Talkies into oblivion. By December, the Nagaon landmark was rubble.

Krishna Talkies and its legacy

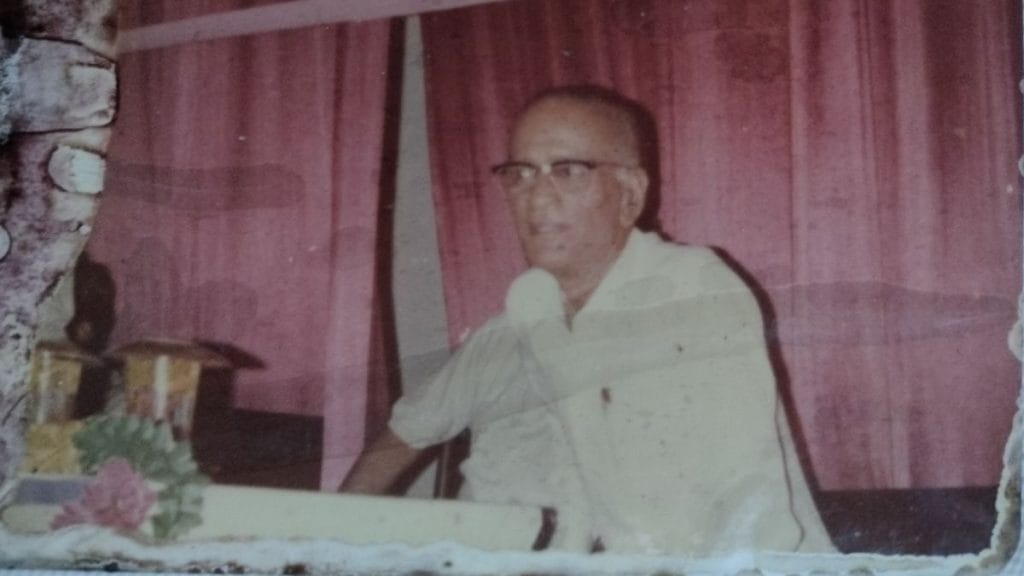

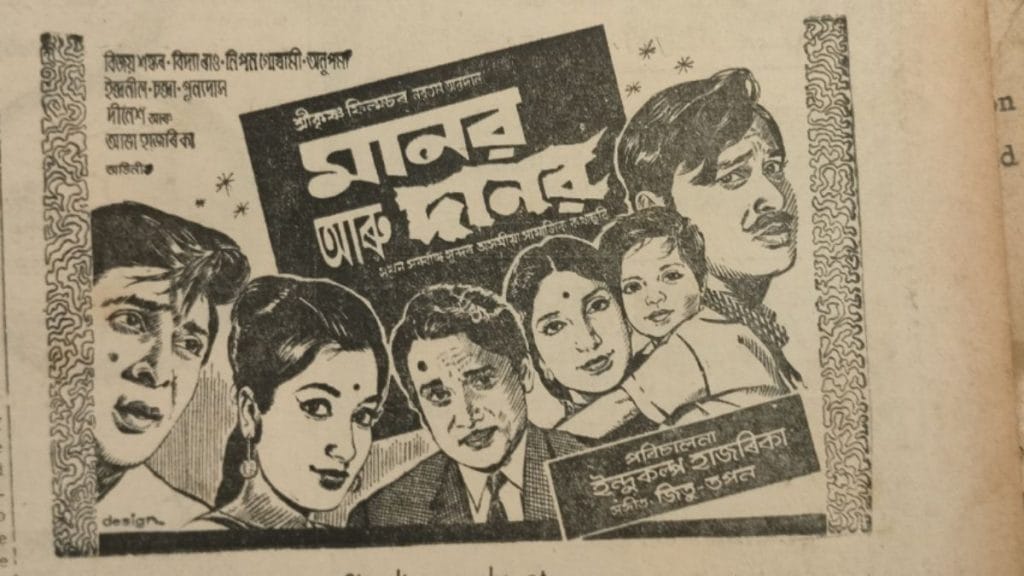

Krishna Talkies was part of a wider ecosystem built by Kashi Prasad Bihani, an entrepreneur and cultural enthusiast whose influence went far beyond running cinema halls. Through his banner Shree Krishna Films, Bihani had produced filmmaker Asit Sen’s debut film, Biplabi (1950), one of the early Assamese feature films, and later Manav Aru Danav (1971), which at the time were among the state’s largest productions.

His distribution network introduced films by Bishnu Prasad Rabha, Bhupen Hazarika and Tapan Sinha to Assamese audiences at a time when regional cinema needed patrons as much as talent.

“Despite not being natives, the Bihani family made an immense contribution to regional cinema by supporting regional filmmakers,” said film scholar Parthajit Baruah.

The Bihani family also built and managed a chain of halls across Assam — including Apsara Cinema in Guwahati, Shree Laxmi Talkies and Krishna Talkies in Hojai, Bharati Talkies in Lanka, Sree Radha Cinema in Lumding, and Urvashi and Chitralekha Cinema in Golaghat.

What disappears with a hall

After the death of Kashi Prasad Bihani, the Apsara group of cinema halls were managed by his sons and grandsons, including Jagadish Prasad Bihani, Swapan Kumar Bihani and Nitin Bihani. In 2007, it was Nitin Bihani’s Chitralekha Cinema that led the way for digital cinema projection systems in Assam but those didn’t survive for long either.

“The cinema hall was an important recognition for the Bihani family. But unfortunately, the future generations couldn’t hold on to it,” actor Jatin Bora said, whose Ratnakar (2019) registered a successful run in Krishna Talkies.

National award-winning filmmaker Arup Manna says every generation cannot carry on the family trade.

“Two generations of their family have successfully carried forward the trade until the next one chose to discontinue. It’s natural, even if it is hard to accept,” Manna said.

For actors and filmmakers in Nagaon, Krishna Talkies remains a familiar memory.

“During our younger days it was a routinely frequented destination,” said Bora, who is from Nagaon, recalling crowded festive screenings and even police lathis during Durga Puja rushes. Almost all his films, including Hiya Diya Niya (2000) and Uttarkal (1989), opened there. “I still remember putting up posters for my first film myself,” he said.

Manna recalled how Krishna Hall was an everyday destination for them during schooldays.

“We would always go to see the poster artists who came from Bombay and made the big hand-drawn posters for new releases. It is a nostalgia of a different kind,” he said.

Today, Nagaon has just two operational theatres, both on its outskirts. One is Divyajyoti, a creaking and tottering single screen with wooden benches; the other, Opera Cinemas, is a new multiplex with ticket prices beyond the reach of most locals.

OTT and the death of cinema

Nagaon has already lost Jayshree, Elphinstone and Aditee cinemas. With Krishna Talkies gone, the centre of Nagaon is left without a single screen.

Arup Manna fears the implications: “The audience for Assamese cinema has always been the common people. But today, they are no longer able to afford it.”

Discussing the impact of OTT platforms on cinema halls, Manna observed, “OTT is the hot cake right now, so it’s obvious that people will consume it. I think we are not very far from the day when the concept of the cinema hall itself will cease to exist”.

The land where Krishna Talkies stood has reportedly been sold to a nearby socio-religious institution, with the owners choosing a non-commercial future for the site. The decision is irreversible.

“For towns like Nagaon, halls like Krishna and Jayshree were lifelines,” film scholar Baruah said. “It is very unfortunate that today none remain.”

He has an appeal for the government.

“There is a dire need for establishing a cinema hall at the heart of Nagaon. If materialised, it would go a long way in bringing back the town’s cultural life,” he said.

Unless the right policy steps in, Assam’s cinema may retreat further into private living rooms. But for those who grew up under its flickering projector, Krishna Talkies will endure as a reminder of a time when going to the movies meant something more than pressing play.

(Edited by Stela Dey)