Barh/Nalanda: From a bed on the seventh floor of Patna’s Big Apollo Spectra hospital, 19-year-old Arti Kumari looks wistfully out of the window. An international rugby star, she is now recovering from a painful reconstruction surgery to fix a torn ligament in her knee. Her mind, though, is in Kolkata’s national rugby camp that she’s missing out on.

But her father has good news for her.

“International medal-winning players will now become SDOs and DSPs directly,” Sanjay Kumar’s eyes light up as he reads out the headline. Within seconds, the hospital room fills up with joy. Arti posts the news clip on her WhatsApp story.

The proud father immediately rang up a few relatives. He also ran around the floor, telling security guards, nurses and other staff: “My daughter is going to be a daroga.” using the Hindi word for police officer.

Everyone from the nurses to the guards celebrated with him. They understood the lure of a government job having perhaps nurtured the dream at some point in their lives. But what they didn’t understand was rugby.

How do you play this game? Is it like football? Is it like volleyball? What does the ball look like? The questions kept coming. Kumar spent the next half hour explaining the game to them. A few curious staffers took out their phones and started googling rugby while the others gathered around them to watch how this unknown game that would get Kumar’s daughter a government job was played.

“It looks like a dangerous game,” said a security guard after watching players with no headgear or padding carry, pass and kick an oval ball. They tackle each other in seemingly savage clashes to prevent the other team from scoring.

Well-meaning relatives and family friends and their friends have been critical of Arti Kumari’s choice of sport. But today, in her hospital room, she is triumphant.

“I’m getting so much respect from the same people who once protested my freedom. Nobody dares ask me a question now,” said Arti, a national champion and rising star in women’s rugby in India. “And I get to see the world. It is so much fun.”

In Bihar, hundreds of girls like Arti are embracing the sport, upending the stereotype popularised by the adage that rugby is a game for hooligans, played by gentlemen.

In many rural pockets of India, it is now no longer a game played by men or elites, but by young, poor village women called Shweta, Sweety, Beauty, Kavita and Sapna. Bihar won the in both the junior and senior categories at the Rugby National Championship in 2022, defeating Odisha in the former category and West Bengal in the latter.

It is a feat that has been a decade in the making — from a lone ranger coach’s search for talent to convincing conservative parents to send their daughters to explaining rugby to cricket-crazy Indians to getting the Bihar government to root for them.

Rugby, a quintessential English sport, is unlocking unimaginable possibilities for Bihar’s poorest families.

“It is a window to look beyond poverty for these girls,” said Pankaj Kumar Jyoti, 43, the rugby association secretary and coach in Bihar, who introduced this sport to Arti.

Also Read: WPL changing cricket crowd culture. Kids in stands scream Jemimah, men now say ‘batswoman’

A deserted sugar mill and a long jump

Sports was never in Arti’s genes. Agriculture is her family’s mainstay, and even the men in her family have never entertained the thought of breaking from tradition. The four bighas of land that her father tills in their hometown in Nawada district’s Warisaliganj, ensured that as a child Arti never went hungry. Everything else, including athletics, was a luxury.

Her ‘training’ ground was a 78-acre campus of the defunct and deserted Warisaliganj Sugar Mill. Abandoned since 1993, it is overrun with unmown grass, weeds and trees that stand sentinel around dilapidated buildings and sheds.

It’s where she attempted her first long jump and 100-metre race.

“When I was 14 years old, I used to see some boys playing on the ground. I joined them too,” said Arti. Her interest in athletics brought her to Patna in 2016 where she participated in the Open State Championship. “I bagged second prize in 100 and 200-metre race,” she recalled.

This was where rugby association secretary Pankaj Kumar Jyoti spotted her. He was looking for fast runners with the stamina to train and play rugby at the national level. By the time he approached Arti, he had already ‘discovered’ Shweta Shahi from Nalanda and Sweety Kumari from Barh—both top players who have put Bihar on the national and international rugby map.

Much like the hospital staff, Arti had never heard of rugby. She didn’t know what to make of Kumar’s offer to coach her. It took a little bit of convincing on his part before she agreed to give it a shot. Her father supported her decision though he, too, hadn’t heard of the game.

A year later, in 2017, she was invited to watch the state rugby championship, held in Rajgir where she saw Shweta Shahi and Sweety Kumari in action for the first time. The movement and power of the game and the no-holds-barred celebration of speed and strength fascinated her. “It was surreal,” she said.

Suddenly, her life was a flurry of intense learning. She joined a 45-day boot camp in Patna. She learned how to hold the oval ball, how to pass it, and how to tackle the opposing team. And then the games began. The same year she went to Hyderabad for an inter-school tournament where the team won gold. Soon, she was representing Bihar state playing alongside Shweta Shahi and Sweety Kumari.

They brought home one silver, one bronze and three golds in the Junior National Rugby National Championships over the years. Last year, she played in the senior nationals, where the team bagged Bihar a gold.

Her prowess at the game gave her the opportunity to see the world. In 2021, she and Sapna Kumari from Bihar were selected to represent India on the international stage. The team travelled to Uzbekistan for the Under-18 Asian Championship where they won a silver. She was also a part of the team that won a silver in Asia Rugby Sevens Trophy held in Jakarta.

But while playing in the All India 15’s Championship in Odisha, which took place from 28 January to 4 February, she injured her knee and missed out on the opportunity to play a friendly rugby match in Borneo.

“I terribly miss being there,” said Arti as she watches clips of two of her favourite rugby players on YouTube, New Zealand captain Stacey Fluhler and India’s rugby captain Vahbiz Bharucha.

Sweety Kumari stops by to check in on her. She calls Arti regularly as well. Arti is family, and a key player in the rugby revolution that Pankaj Kumar started more than ten years ago.

Also Read: ‘No panga with minister’—Haryana woman sprinter’s lone battle against sexual harassment

A decade of change

As a state-level athlete, Pankaj Kumar was drawn to the beauty and power of the game. So when he got a government job under the state’s sports quota in 2012, popularising the sport in Bihar became his mission.

He started touring the state in his capacity as secretary of Bihar’s Athletics Association. His mission was to find boys and girls with speed and strength. It was almost like a page out of the Bollywood blockbuster Chak De — the assembling of talent.

It was easy to convince parents to send their sons to training camps.

“But for their daughters, it was so difficult. They were suspicious because the request to play an alien game was coming from a male coach,” recalled Pankaj Kumar. There were days when the task seemed impossible to him. But with Shweta Shahi from Nalanda, the revolution started to take shape.

“I first spotted Shweta during my tour in Nalanda,” he said. Whatever little knowledge of the game he had gained from his interaction with rugby players outside the state was passed onto Shahi, and the rest she learnt from YouTube—the new age Guru.

Shweta soon played in national and international tournaments and became a household name in Bihar.

“Her selection [into the national team] was a huge deal. We got so much attention,” said Pankaj Kumar, who is based in Patna. He started involving district secretaries in his mission, and gave them a task: Spot any teenage female athlete with speed and let him know.

More than 70 kilometres from Patna, Gaurav Chauhan, an international rugby champion, from Barh heard the clarion call. The small town on the southern banks of the Ganges was home to young teenage women who excelled in sports. Together they spotted Sweety Kumari in Barh stadium and convinced her to play rugby.

Sweety has won international acclaim, bagging the International young player of the year award from Scrumqueens in 2019. She has also been dubbed the ‘fastest player in the continent’ by Asia Rugby, the governing body of the rugby union in Asia.

Now, Pankaj Kumar no longer has to beg parents to let their daughters play rugby. Every day, he is inundated with requests and reels from athletes and their parents from across the state. And Barh is as much a hub as Patna.

“If 250 athletes train every day in Barh stadium, more than 70 per cent are women,” said Chauhan, standing in the middle of the stadium. Most of them are between the ages of 15 and 17.

Apart from being an inspiration to school-going girls in small hamlets, Sweety, Shweta and Arti, are also changing the public perception of Bihar. Kumar will never forget the time when he felt embarrassed of his home state.

“People would say that we Biharis would never learn. Today, the hurtful taunt has turned into, ‘This [trophy] will go to a Bihari now.’”

According to Kumar, if there is a training camp for the Indian team, at least four or five girls out of 50 will be from Bihar. He’s got his eye on the 2028 Los Angeles Olympics—and a new generation of players like Gudiya Kumari, 18, a daughter of a daily wage labourer, are waiting to become the next Sweety and Arti.

Bihar is emerging as a standard bearer for rugby. Kiano Fourie, a South African rugby coach who was recruited by the Bihar government to train the sportswomen in 2022, is not surprised. He is impressed by their determination and drive to win and the intensity with which they played the game.

“When you watch and listen while the ladies play you really get a sense of how much the opportunity means to them,” he told ThePrint in a telephone interview.

“They have skill, speed, power and endurance.”

State patronage

Unlike Odisha and Haryana, which have cultivated a rich sports culture backed by strong sports policies, Bihar’s teenage girls had to first become winners and prove themselves to demand state patronage, cash prizes and respect. It was a long, and lonely battle.

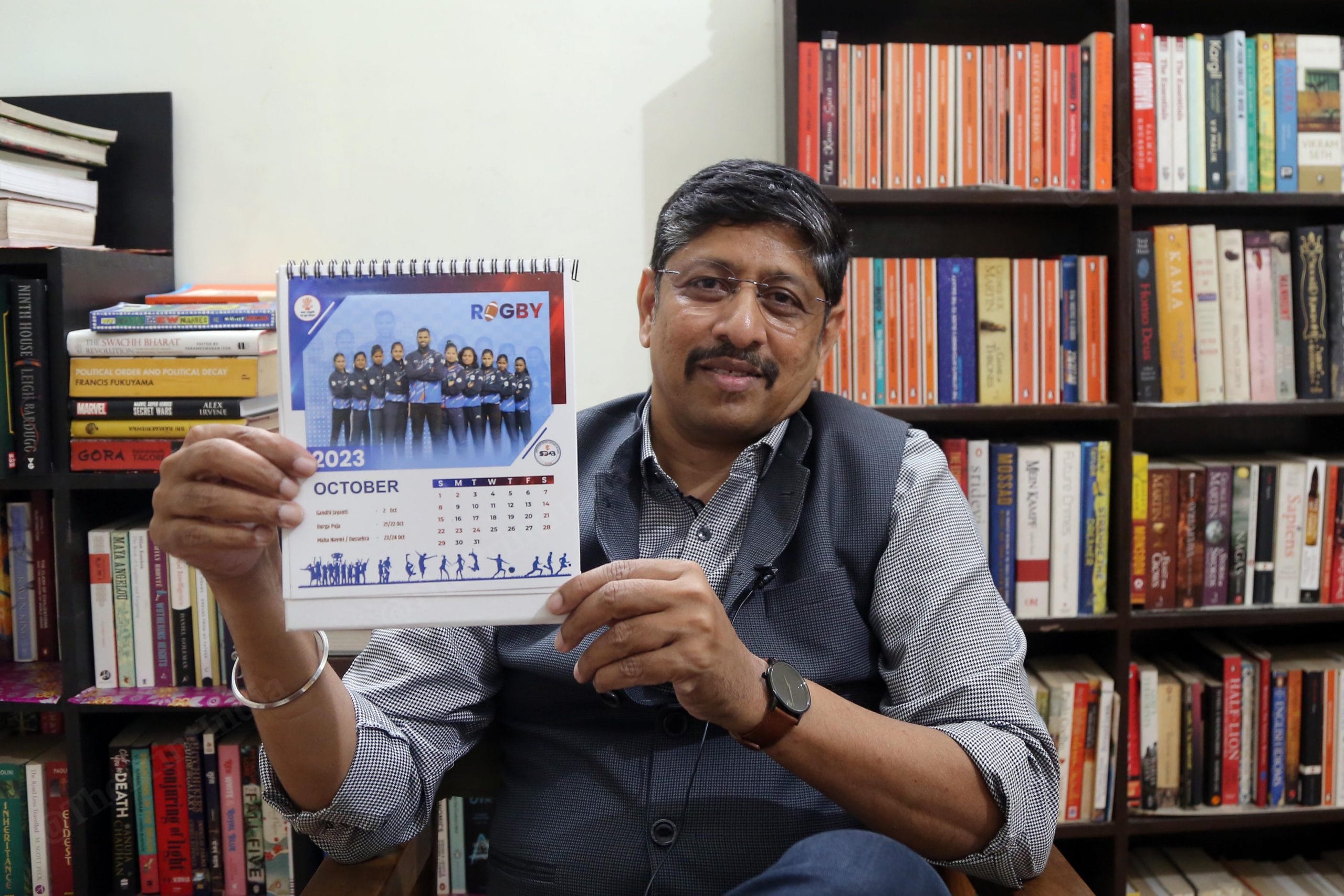

“A lot of credit goes to the success of the girl’s rugby team,” said Raveendran Sankaran, director general, Sports Development Authority of Bihar. He brought out a table calendar that has Bihar’s girls rugby team on its cover.

“They have arrived,” he declared.

A year ago, the government asked him to tour the state and find talent to shape Bihar’s sports policy. One word resounded in every corner of the state: Rugby. When he presented his findings to the committee, the members were shocked.

“They kept asking me, rugby? Are you serious? Have you done proper research?” he recalled. The next task was to prove that Bihar’s junior and senior rugby teams were champions.

“We decided to host the national championship in our state,” said Sankaran.

In 2022, Bihar not only hosted the National Rugby Championship but its young female players won gold in two categories.

The team members were instantly taken to meet the chief minister and were awarded cash prizes.

“A message went through the state [that the government was taking the sport seriously].” Sankaran was vindicated, but then he had to wade through red tape to secure government jobs for the rugby players. “One has to apply, advertise and give trials and wait for years to get that job,” he said.

In February this year, Bihar’s cabinet finally approved the Bihar Outstanding Sportspersons Direct Appointment Rules 2023 with the tagline — medal lao, naukari pao (win a medal, get a job). Under this policy, winners in national and international games will be recruited for group B and C jobs.

“It is a landmark decision,” tweeted Bandana Preyashi, secretary cooperative & secretary Art, Culture, Youth & Sports.

Also Read: Watching IPL on TV, this Rajasthan village girl bowled her way to ‘other side of screen’

The challenges

Actor Rahul Bose, who is the national president of the Indian Rugby Football Union, is often seen travelling to the deep pockets of Jharkhand, West Bengal and Bihar, meeting parents and encouraging them to allow their girls to train for their game.

Earlier this month he announced that the governing body of the sport had mapped out a plan to help India’s ruby teams qualify for the Asian Games in 2022 and the 2028 Olympics in LA.

“It would be really big if either men’s or women’s rugby teams, if not both, reach the Olympics 2028… we have sent only teams for hockey in field sports,” Bose had said.

But the freedom, the medals, the government jobs, and the pride comes at a heavy price. Beyond the lack of social support, infrastructure and medical facilities is the real threat of injuries.

Most of the teenagers Arti Kumari met when she saw her first rugby game in 2017 have quit playing it professionally. “The didis no longer play games and most of them are married now,” said Arti Kumari. And she’s not the only one nursing injuries. Dharamshila Kumari, better known as Beauty, and Sweety were coping with injuries.

Dislocated shoulders, torn ligaments and knee injuries are commonplace.

While Arti was treated in Patna itself, Sweety and Beauty had to travel to Delhi and Mumbai for their treatment. Since Sweety took up the game, eight years ago, she has undergone four surgeries including two for shoulder injuries.

“When she started playing and got injured for the first time, we were so scared that nobody would marry her. It was so painful to see her injured face,” said Sweety’s father Dilip Kumar Chaudhary.

Abhishek Kumar Das, the surgeon who performed the keyhole surgery on Arti says it is a valid fear. The players need access to cutting-edge rehabilitation and physiotherapy centres, which are few and far between.

“I was in the UK for 11 years and worked closely with rugby players. It is a high-level contact sport, second to none. But things are changing in Bihar [private hospitals have begun offering services for sports injuries],” said Das.

Arti can’t wait to leave the hospital bed and get started with physiotherapy. She has been told that she’ll be able to return to the field in six months, and she’s looking forward to playing the game she loves with the young women who have become her family away from home. She can’t afford to miss out on training sessions.

Across Bihar, from Patna to Barh, teenagers and younger girls are practising and waiting in the wings for a spot in the team.

At a stadium in Barh, seven-year-old Srishti Raj runs with all the speed she can muster.

“Ball, Srishti, ball. Dekh ke, Sristhi,” someone hollered across the stadium. Raj has big goals, she wants to become the ‘man of the match’ one day. She lives in a nearby slum and rugby is her way out. She is still learning to pronounce rugby. She calls it ‘lugby’.

Her idol Sweety Kumari is in the wings, recovering from her ligament surgery, watching over her.

(Edited by Theres Sudeep)