New Delhi: “I had an Indian dream like others had an American dream.” This is how 32-year-old French author and documentary filmmaker Valentin Hénault begins his latest book, reflecting on his experience in 2023 when he travelled to one of his dream destinations — a journey that soon turned into a nightmare.

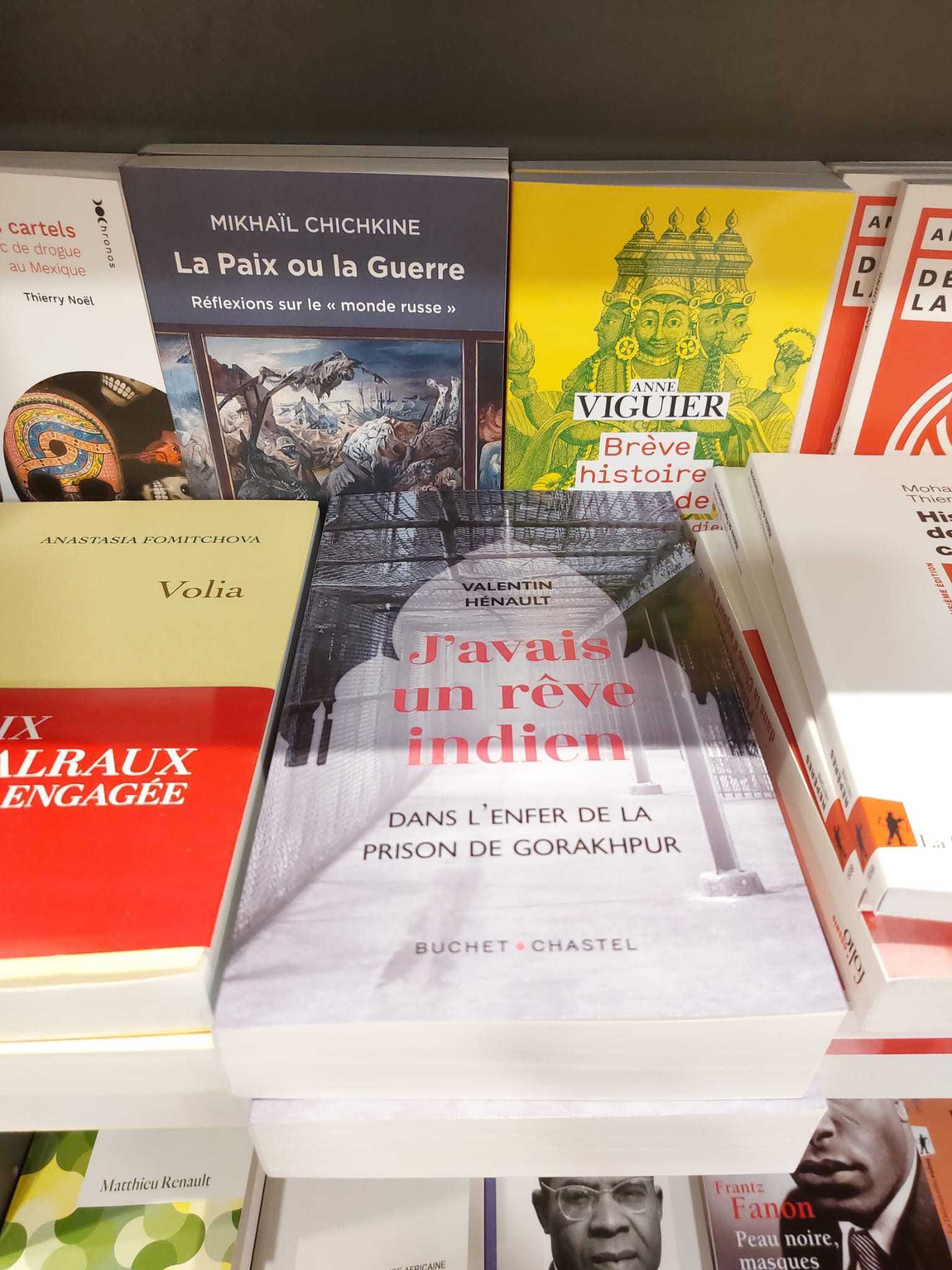

The book titled J’avais un rêve indien. Dans l’enfer de la prison de Gorakhpur, launched in India on 15 January 2026. Its direct English translation reads: “I Had an Indian Dream: In the Hell of Gorakhpur Prison.”

“It’s my personal story — the month I spent in Gorakhpur jail. And it’s also the stories of the other inmates I met there,” Hénault told ThePrint in an exclusive interview.

Hénault came to India in 2023 to work on a documentary project about the lives and struggles of Dalit women in several northern states, including Bihar, Jharkhand, and especially Uttar Pradesh.

He was visiting on a business visa with the intention of researching and filming stories related to caste-based discrimination and atrocities faced by Dalit communities. However, during his visit to Gorakhpur, he was arrested by the Uttar Pradesh Police for allegedly being part of a protest and violating the terms of his visa.

Structured into around 16 chapters and only available in French, the book explores multiple layers of life behind bars. It traces the struggle of prisoners for survival and documents what he describes as the harsh realities of caste dynamics within the prison.

“This is a story of survival — how, in extremely hard conditions, you try to maintain yourself, to stay powerful, energetic, to keep yourself alive,” Hénault recounts.

What happened in 2023

Sitting in his room, a coffee mug in his hand, Hénault recalled the bitter experience and the exact moments of his arrest — moments that turned his visit to India into a terrifying ordeal.

After visiting Bihar and Jharkhand, Hénault reached Gorakhpur. The day of his arrest began as a normal and uneventful day.

He attended the “Ambedkar’s People’s March” (Ghera Dalo, Dera Dalo protest) in Gorakhpur on 10 October 2023, which focused on land rights for landless Dalits, OBCs, and Muslims.

“I was just there. I was not filming anything. I was just present,” he said. “After maybe ten minutes, the police saw that there was a white guy in the crowd, and they came and surrounded me.”

That night, officials came to his hotel, arrested him, and sent him directly to the police station.

Though officially charged with a business visa violation, Hénault claims the true motivation was political.

“I think the real goal of the arrest was to make a little media buzz about how a heroic police force in Gorakhpur arrested a dangerous foreigner, because they didn’t really have a judicial, legal matter on which they could base my arrest,” he said.

Hénault was also accused of ‘foreign involvement,’ including allegations that he had funded the protest. However, no credible evidence of illegal funding was established, and he was later released. He was eventually allowed to return to France in 2024.

“I think there was another reason because I was on a business visa in the name of a production company. What they stated later in the charge sheet was that I had violated the terms of my visa by illegally financing NGOs. I was not financing anything,” said Hénault.

From local outlets to national media houses, his arrest received widespread coverage. PTI ran the headline, “French national arrested in Gorakhpur for violating visa norms.” A Hindi daily reported, “UP mein ghazab! Business visa par aaya French nagrik, bheed mein chhupkar kar raha tha ye kaam; purv IG sahit saat giraftaar.”

Other Hindi newspapers carried headlines such as, “Jharkhand tak anumati, Gorakhpur mein ghoom raha tha videshi nagrik,” and “Ambedkar Janmorcha andolan mein shamil videshi.” In 2024, The Wire published, “Jailed after attending Dalit march in Uttar Pradesh, French director’s year-long ordeal finally ends,” after he was permitted to return to his country.

“He was allegedly participating in activities in Gorakhpur district that were not permitted under his business visa, which constitutes an offense under Section 14B of the Foreigners Act, 1946,” reads the FIR filed at Cantt Police Station in Gorakhpur, Uttar Pradesh, on 11 November 2023. ThePrint has a copy of the FIR.

Once inside Gorakhpur jail, the stark conditions shocked him.

“There was no space,” he said, recalling his first night. “There were 300 people in the same barrack. I had no space to sleep or turn around.” He said he slept on his side, pressed against strangers. “It was absolutely packed.”

Beyond the infrastructural and facility problems, what truly broke him emotionally was witnessing people dying in front of his eyes.

“I’ve seen people dying in jail. The guards didn’t open the door. This is very shocking.” Hénault shared how deeply affected he was by the human suffering he witnessed.

However, in between all this, he was treated comparatively better due to his foreign status, though he did not miss the inequity.

“For me, it’s white privilege, which is also disappointing for me.”

Visible hierarchies inside the jail

Graduating with a master’s degree in finance at 20, Hénault decided to leave everything behind to make documentaries.

Before writing his prison memoir, Hénault built his career through a series of independent films and documentary projects.

His first short documentary, L’Homme du sous-sol (2019), explored the mystical wanderings of a homeless man beneath Paris’ business district and was selected at an international documentary film festival, Cinéma du Réel, in Paris. His next project, Michel et la vague jaune (2020), engaged with contemporary social movements in France. In 2022, he wrote and directed La Désertion, a black-and-white fictional short about children creating their own world in an abandoned village. His first feature documentary, Les Repentis (2023), follows the journey of a Roma man grappling with identity and social exclusion.

The experience in Gorakhpur weakened Hénault physically, but the psychological strain was worse. He called it “mental torture.” People in jail don’t know how long they will be there without any hearings or court appearances.

The first pattern of hierarchies Hénault noticed in the Gorakhpur jail was caste and religion-based discrimination.

“There is one barrack where they used to put all the Muslims in the same place,” Hénault said.

Discrimination inside the jail was clearly visible. Upper caste people openly occupied the relatively better central areas, Hénault said.

“People were Brahmins in the center. And then next to the toilets, where it’s very dark, were dozens of people, obviously from lower castes,” he said.

Hénault used to communicate with inmates who knew English. However, spending more than two months in India also taught him a little Hindi, which he used to communicate with other inmates.

“Thoda thoda Hindi aata,” he said.

Also read: 100 Ways to See India: Stats, Stories, and Surprises captures the country’s diversity

‘I still love India’

The moment Hénault entered the jail, after witnessing the conditions for some time, what he really looked for was not space, food, or comfort—but a pen and paper.

“From the very first day, I tried to get a pen, to get paper, and start writing everything I was witnessing. It really allowed me to find a sense of being in jail. And to resist. It was a kind of resistance—to write.”

His book is gaining a lot of traction in India. People, on one hand, are asking for a translation, while others comment on how an outsider is holding a mirror to the Indian system.

According to the author, French readers were shocked after reading his book. The image they had of India as a harmonious and spiritually unified country was broken.

“They didn’t know that India was such a corrupt state, that the caste system was still so powerful,” he said.

Yet Hénault’s reflections are not purely condemnatory. “I still love India,” he said. It’s just that his experience has changed the way he sees the country now.

“I have a more political vision of what India is now and less exotic.” The romanticism has faded, replaced by what he calls clarity. “It means that I broke a reflection. I’m seeing more clearly what India is.”

(Edited by Ratan Priya)

Did he visit french prisons ? Just to compare.