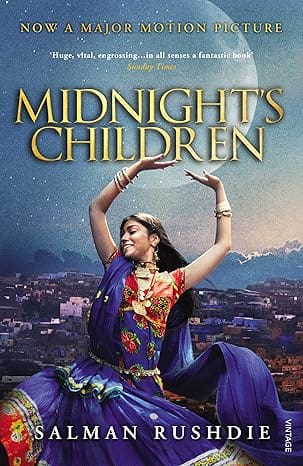

New Delhi: In 1984, Indira Gandhi sued Salman Rushdie over a single sentence in his Emergency-inspired 1981 novel, Midnight’s Children—and won.

“It has often been said that Mrs Gandhi’s younger son Sanjay accused his mother of being responsible, through her neglect, for his father’s death; and that this gave him an unbreakable hold over her, so that she became incapable of denying him anything,” read the sentence.

Rushdie’s lawyers issued a formal apology; Gandhi requested nothing in damages—not even a symbolic one rupee—except that the sentence be removed from all future editions, recalled Harish Trivedi, a former professor of English at the University of Delhi. “As soon as she passed away, Rushdie brazenly reinstated the sentence,” Trivedi told ThePrint.

This year marks the 50th anniversary of the Emergency, a bleak yet defining moment in India’s history. It began on 25 June 1975, when democracy was suspended, and authoritarianism took hold. As the nation reflects on this dark chapter, the stories and literature born from that era remain urgently relevant, offering a vital window into the human experience beyond official records and political rhetoric.

Saleem is symbolic of India. In Rushdie’s phrase, he is handcuffed to history. He is disintegrating. And in Rushdie’s view, India is disintegrating. That was the view of many Western people, especially after the emergency was declared, but even before that.

Harish Trivedi, former English professor, University of Delhi

Writers who lived through the Emergency witnessed firsthand the silencing of dissent, the erosion of civil liberties, and the widespread fear gripping the country.

While nonfiction accounts – from Jayaprakash Narayan’s Prison Diary (1977) to JP Goyal’s Saving India from Indira (2025) – documented the Emergency’s political upheaval and repression, fiction and the arts focused on the deeper impact—its trauma, resilience, and contradictions. Gulzar’s temporarily banned film Aandhi (which later inspired the novel Kali Andhi), Salman Rushdie’s allegorical Midnight’s Children, Rohinton Mistry’s unflinching A Fine Balance (1995), and Nirmal Verma’s haunting Raat ka Reporter (1989) emerged as acts of remembrance and resistance.

“In fiction, there are no neat and tidy ‘Emergency’ narratives: all these novels have a before and after story. The narrative of the Emergency, inevitably, is the interrogation of the narrative of the democratic nation-state. Comprehensive articulation of this narrative became clear only afterward, as it tests several largely unquestioned beliefs about India’s democracy,” said Anupama Jaidev, associate professor of English at Delhi University’s Maharaja Agrasen College.

Also read: Hindi literary mag Nayi Dhara gets a reboot. For Ashoka University founder, it’s personal

Bodies and homes under siege

The Emergency pushed writers to explore new ways of capturing its impact, with novels spanning genres from magical to social realism. Midnight’s Children, for one, blends the surreal with history through magical realism.

One scene from the book depicts forced sterilisations during the Emergency: Government agents arrive in a makeshift sterilisation facility, their boots clattering loudly on its floors. PM Indira Gandhi, known as “the widow” in the novel, is about to unleash her quiet terror on unsuspecting victims.

Saleem Sinai, born right at the moment of India’s independence with magical gifts, is taken to a cold, bright room, with silent doctors in green gowns moving about him without emotion. He is laid on a steel table, pants stripped away. “Count,” someone orders. “One… two… three…”

And the magic within him is stolen.

As Saleem steps into the morning sun, he is hollowed out. He once carried the secret link between all ‘midnight’s children’ – a living memory of India’s birth. But now, that shared bond has been severed.

“The political crisis didn’t spark Rushdie’s novel–it happened to coincide with his search for a story. At the time, he had no clear plans. His first novel had just flopped, but he received a modest advance of about £700. With that, he travelled to India in 1975. By sheer chance, the Emergency was declared during his visit. In that sense, the story landed right in his lap,” said Trivedi.

In Midnight’s Children, Saleem’s personal collapse by age 30 is intended to mirror the fracturing of India itself.

“Saleem is symbolic of India. In Rushdie’s phrase, he is handcuffed to history. He is disintegrating. And in Rushdie’s view, India is disintegrating. That was the view of many Western people, especially after the emergency was declared, but even before that,” Trivedi stressed.

Ever since India got independence, Trivedi added, “they felt that India can’t hold together now that the British are gone. Rushdie buys that completely. So in his novel, Saleem is falling apart, and so is India. That’s his dystopian vision.”

Social realism

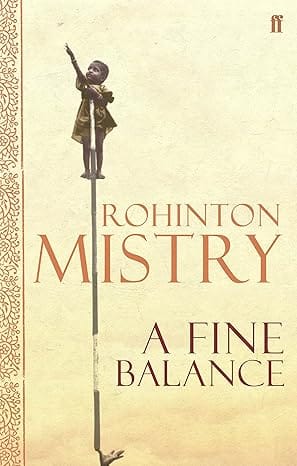

A Fine Balance is more rooted in social realism. It focuses on four diverse characters whose lives intersect in a city apartment, showing the brutal impact of government policies such as slum clearances on marginalised communities.

Dina Dalal, a determined Parsi woman who has lost her husband, runs a small tailoring business with Ishvar and Omprakash Darji, Dalit relatives fleeing caste violence in their village. Joined by Maneck Kohlah, a privileged student who is also a boarder at Dalal’s flat, they form a fragile household built on trust. But the Emergency shatters their lives: their slum is razed in a “beautification” drive, and they endure forced labour and sterilisations.

In one scene, Ishvar and Om stumble through rubble – forced into gruelling manual labour after losing their tailoring job with Dalal and the destruction of their home. Bulldozers roar, scattering tin huts like debris. Straining under a gravel basket, Ishvar gasps, “This isn’t work for tailors.” The overseer snaps: “Pile it to the brim. You are not paid for filling half-baskets!”

“The book steers clear of the grand narratives of the Emergency and focuses its attention on the predicament of the urban poor. The often rootless and anonymous urban poor are cast as subject to a continuing, albeit different kind of isolation and abjection in cities, than the feudal/communal/casteist authoritarianism of the hinterland they seek to escape,” said Jaidev.

The book focuses on more than just slum demolition and forced sterilisation, showcasing amputation, castration, and four suicides.

Also read: Sahitya Akademi is promoting Ramayana, Modi policies. But also queer & Dalit writers now

Fear, memory, and resistance

Even before the Emergency officially began, artists were already capturing the anxieties of a crumbling democratic spirit. In February 1975, just months before the Emergency, Aandhi, directed by Gulzar, quietly entered cinemas. It told the story of a fearless woman politician, with no mention of Indira Gandhi. But its portrayal of political ambition and democratic spectacle felt uncannily familiar.

Even before the Emergency officially began, artists were already capturing the anxieties of a crumbling democratic spirit. In February 1975, just months before the Emergency, Aandhi, directed by Gulzar, quietly entered cinemas. It told the story of a fearless woman politician, with no mention of Indira Gandhi. But its portrayal of political ambition and democratic spectacle felt uncannily familiar.

Though cleared by then-Information and Broadcasting Minister IK Gujral and allowed a short theatrical run, it was swiftly banned once the Emergency began. Years later, the film’s co-writer Kamleshwar returned to the story in novel form, naming his book Kali Andhi.

“How can it portray the Emergency if it was completed and released before it? The film focused on general political cynicism–not the Emergency itself–Gulzar’s sharp satirical song on political machinery hinted at its message. The ban only confirmed these suspicions. Later, the Janata government lifted the ban and aired it on Doordarshan,” said Trivedi.

Some authors tapped into the undercurrent of the Emergency–its fear, despair, and quiet ruin–and weaved it subtly into their stories. They drew on both the emotional charge the word ‘Emergency’ evokes and the deep scars it left on the people and the nation.

The routine invocation of the Emergency at its best serves as a warning against the totalitarian streak that can and does surface in our democracy, as in others. Lest we forget that our hard-won democratic rights need to be carefully protected.

Anupama Jaidev, associate professor of English, Maharaja Agrasen College

Nirmal Verma’s Raat ka Reporter is an example of such a work. It’s among his most overtly political works–an exploration of life under totalitarian rule during. Here, Verma chose to immerse readers in the atmosphere of fear. No torture chambers, just silence and an unnamed threat. No protests, just anxiety and a general atmosphere of menace.

The story follows Rishi, a journalist recently back from Bastar, who finds himself under the shadow of state surveillance. A stranger warns him: he could be arrested any moment. What follows is a slow descent into paranoia and doubt. Each detail–a ringing phone, a changed signboard, a girl’s sudden disappearance–becomes an omen. In this world, nothing is certain. Truth feels dangerous. Trust evaporates. An arrested man’s message to his wife–burn all my papers–adds to the silent terror.

Raat ka Reporter is not just about fear of the state. It’s about the fear within–how external oppression pushes a man into introspection. Rishi begins to question not just censorship or the role of journalism, but his own motivations. What is the point of writing? Is there a truth that survives surveillance?

“It’s like [Franz] Kafka in some ways. But with a difference. Kafka’s threat is nameless, faceless, metaphysical. Here, the fear is human. There is an arrest. There’s a state. But the threat isn’t spelled out. It creeps in silently–oppression without specifics, suspicion without clarity,” said Trivedi.

In most political novels, especially about the Emergency, the enemy is clear: censorship, violence, tyranny. But Verma does something more unsettling. Just when you expect the narrative to stay fixed on the journalist’s fear of arrest or state surveillance, it turns inward–to Rishi’s relationship with his mother, his guilt, his emotional distance, the disintegration of intimacy. The political crisis becomes a mirror for a personal one.

The novel refuses to separate public and private life and suggests that totalitarianism isn’t just about jails or bans–it seeps into how people love, grieve, and relate. He portrays how fear in the streets leads to silence at home.

“During the Emergency, Seminar Magazine–asked Verma to write. And he said yes, but only on one condition: ‘Not a single word will be changed.’ Because at that time, everyone had become their own censor. Everyone was scared, protecting themselves. Romesh Thapar agreed. They published it. And the journal was immediately banned. Seminar didn’t appear again during the Emergency,” said Trivedi.

While Verma immersed readers in the suffocating fear of state oppression, Rahi Masoom Raza’s Katra Bi Arzoo (1978) portrayed the wider social realities and hopes of ordinary people navigating the same turbulent times.

The novel is set in a small mohalla of Allahabad. Characters like Shamsu reflect on Partition and migration, nostalgically recalling friendships, festivals, and cultural belonging that transcend religious boundaries.

The novel is set in a small mohalla of Allahabad. Characters like Shamsu reflect on Partition and migration, nostalgically recalling friendships, festivals, and cultural belonging that transcend religious boundaries.

“Raza’s urban poor don’t seem to be voyeuristically presented or articulated by an expert ventriloquist,” said Jaidev, highlighting how Indian literature often filters the poor through a privileged gaze. Instead, Raza gives his working-class characters voice, agency, and complexity, grounding their struggles in the political realities of the time without reducing them to mere symbols.

These fictional works didn’t just explore the many faces of the Emergency–they forced readers to confront the brutal realities of a state gone unchecked.

For those who didn’t live through it, the true cost of lost media freedom and crushed dissent remains almost unimaginable. These stories are like warnings carved in ink, preserving memory, breaking enforced silence, and reminding us that the erosion of democracy starts quietly but devastates swiftly.

“The routine invocation of the Emergency at its best serves as a warning against the totalitarian streak that can and does surface in our democracy, as in others. Lest we forget that our hard-won democratic rights need to be carefully protected,” said Jaidev.

(Edited by Zoya Bhatti)