New Delhi: Family photographs are more than keepsakes for professor Özge Baykan Calafato. They provide a glimpse into how people of an era curated their identities and aspirations, and captured changes in their world.

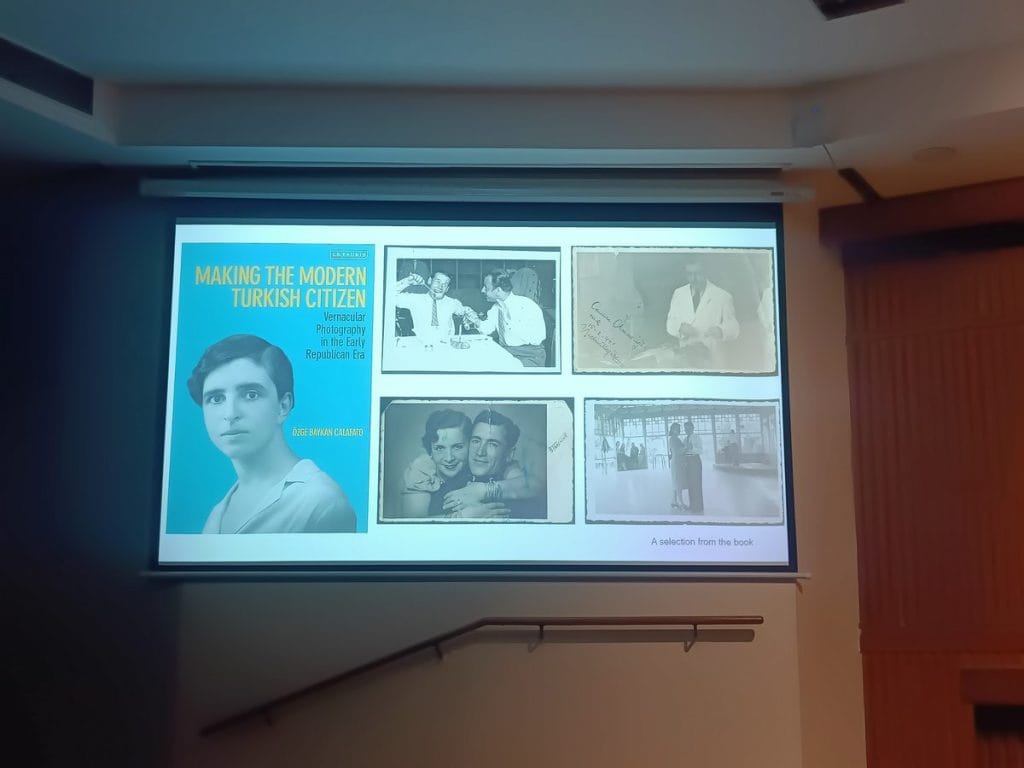

For over a decade, Calafato has salvaged family photographs from flea markets and second-hand shops in Turkey, and turned that archive into her book Making the Modern Turkish Citizen: Vernacular Photography in the Early Republic. Now, she plans to extend her work to India, and trace the photographic legacy of Ottoman princesses who married into the family of the Nizam of Hyderabad.

“I looked at the photographs primarily through the lens of performativity, seeing them as theatres of the self,” said Calafato during a lecture, ‘Memory, Migration and the Archive: The Transnational Afterlives of Family Photographs’ at Delhi’s India International Centre last week. To the lecturer in cultural studies at the University of Amsterdam and Sorbonne University Abu Dhabi, photographs are a “performative space” where people register gender, class, and national identity. Over time, they also become a record of migration and demographic change.

But in India, the same weight is not commonly accorded to family photos, noted Sabeena Gadihoke, photo historian and professor at Jamia Millia Islamia University, who was moderating the talk.

“Family photographs never made it to photo books or scholarly books in India as they were considered common, banal, repetitive,” said Sabeena Gadihoke. “But they are very important because they represent our innermost lives. They bind us not just to family, friends, and intimate others but to community and nation as well.”

Also Read: Prof Shanker Thapa brings Nepal’s rare manuscripts to Delhi. ‘Tradition came from India’

Family photographs as cultural objects

The 17,000 photographs Calafato has collected since 2014 were unearthed in second-hand bookstores and the “ephemeral markets” of Istanbul and Izmir, during a project for the Akkasah Centre for Photography at NYU-Abu Dhabi.

Spanning the late Ottoman Empire through the early modern era, the photographs form an archive of collective memory of the Turkish Republic, especially in the 1920s and 30s. Some of these turned into her book, published in 2022.

In her lecture, Calafato spoke about the cultural economy around such photographs.

“Turkey is quite exceptional in the sense that it remains one of the largest vernacular photography markets alongside Egypt, but this is also changing quite fast,” she said, adding that many images are now moving online as vendors shift to auction and shopping sites.

Photographs are typically sold through second-hand bookstores, she said. Dealers often acquire them for almost no value through junk collectors, paper merchants, or local auctions.

Showing photographs from flea markets, Calafato said dealers curate their stock in special albums, which they tend to show only to serious buyers.

“In the case of Turkey, Ottoman and early Republican era photography has typically been in the domain of private collections or privately owned libraries,” she said, adding that family portraits from the period point to the classed construction of the modern Turkish citizen.

Newly urban middle-class Turks, she noted, actively participated in in the making of the “aesthetics of citizenship” through photographic self-representation.

Even with limited exposure, Calafato added, many were aware of what was happening outside Turkey.

“From fashion to film cultures, they were adopting and adapting quite fast— and the act of photography itself is an act of modernity,” she said.

Also Read: Bhatt family dysfunctionality — ‘It’s more functional than most families,’ says Pooja Bhatt

Partition and ‘population exchange’

Family photographs also speak to the demographic upheavals that shaped the modern Turkish Republic, according to Calafato.

“These demographic currents contain trauma and amnesia that emerged due to displacement, expulsion, death, and assimilation,” she said.

One such rupture came in 1924, when Greece and Turkey carried out a forced population exchange along religious lines. Orthodox Christians were sent from Turkey to Greece, while Muslims were moved in the other direction. New borders of belonging were created and old lives were left behind.

Gadihoke drew a parallel with India’s Partition.

“Because photography was so much of an upper middle-class pursuit, it’s only some families that had photographs,” she said. “But the ones who had, very often had to leave everything behind because when Partition happened, you had to just leave overnight.”

During the discussion, Calafato also spoke about her next project in India, centred on Ottoman princesses Dürrüşehvar Sultan and her cousin Niloufer, who married into the Nizam family in 1931.

“I was excited because of this research and I’m looking again through the photographic legacy and thinking about connected histories and transnational histories… because these histories are also told separately in fragments,” she said.

For the scholar, these photographs gather memory and emotional weight over time. After a decade of rescuing these “sticky objects” from being lost, she urged the audience to hold on to their own collections.

“The photographs I’ve been looking at for a decade have accumulated much emotional weight for me,” she said. “My mission is to urge all of you to look into your family archives and don’t take them for granted.”

(Edited by Asavari Singh)