In 2012, Dipti Kumari was in Ogden, Utah representing India in an international archery tournament. Today, she is pouring hot steaming tea at Argora Chowk in Ranchi, Jharkhand. Archery is the last thing on her mind. All she has now is a Rs 7 lakh loan, a broken bow and the shards of a shattered dream of winning gold in the Olympics and the World Archery Championships.

Stealing a few minutes from a busy day serving customers, Dipti visits the neighbourhood ground where she learned archery with her friends. A new generation of children are now learning how to wield a bow and arrow. They don’t recognise her—almost everyone has forgotten that Dipti Kumari was once a national, award-winning archer. Seeing the children hold their bows, her eyes light up. But the brightness only accentuates the helplessness lurking in the background.

“When I am very upset, I come to the ground. I find some relief here. It is nice to see these children play. I could have played too, but I am forced not to because of my situation,” the 25-year-old says, her hands skimming over a junior player’s arrow.

Dipti’s steep fall is the story of many talented sportspersons in India who challenge and train their bodies and minds, but are unable to overcome their debilitating poverty that imperils their growth. It’s a story of the government inability to spot, hone and hand-hold sporting talent and the lack of an enabling ecosystem. Athlete Geeta Kumar who had to sell vegetables at her hometown in Jharkhand’s Ramgarh district and national karate champion Bimla Munda who was selling rice beer in Ranchi are some of the other sportspersons who have met a similar fate.

Dipti started taking part in archery tournaments in 2006. Her mother took a loan of Rs 7 lakh from a self-help group in 2012 and used Rs 4.5 lakh from it to buy her an international standard bow. While participating in the international tournament in the US that year, the bow broke. Dipti had to sit out the tournament and returned to Ranchi where debt awaited her.

She switched to a bamboo bow, but that automatically made her ineligible to participate in international tournaments.

“I played with a bamboo bow, but then the financial condition of the house started getting worse, so I had to leave the game and open a tea cart,” says Dipti, who has won more than a hundred national medals. After years of serving tea and snacks, she is still repaying the loan with a weekly instalment of Rs 1,000.

“As a competitive archer, I was a winner. But now when I sell tea, I lose every day,” says Dipti as she serves tea to a customer in an earthen cup.

Also read: Won World Cup but no fanfare—Jharkhand blind cricketer waits for better school for kids

A mountain of loan

To get the tea shop going, Dipti took another loan of Rs 60,000 from her friends, using the wheeled stall that belonged to her father.

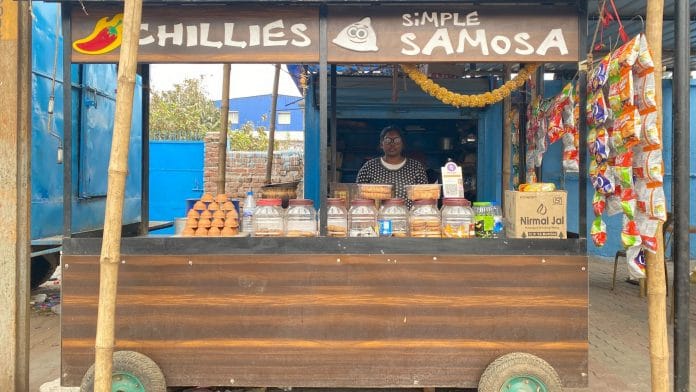

With the new loan, she fixed a tin roof over the stall in the hope that it will attract more customers. A bright red chilly with the name, ‘Chillies, Simple Samosas’ in white lettering stands out.

After Dipti’s story went viral, a local social worker gave her Rs 25,000 with which she repaid her friends. For all the harsh lessons that life has thrown her way, Dipti hasn’t lost hope of playing again.

“If I get a chance, I can still make the country proud. It will take me 15 days of practice, but there are responsibilities at home,” she says. Her mother is a heart patient who recently underwent “kidney surgery”. Her sister suffers from debilitating stomach aches but after multiple tests, there is still no diagnosis. “For this also the family has taken many loans.”

About 15 minutes away from her tea stall, she rents a room and shares a bathroom with ten other tenants for Rs 2,000 a month. About 30 medals hang on an empty wall—a daily reminder of her past life. “Sometimes my brother or sister-in-law comes to stay with me. But otherwise I mostly live alone.”

Dipti can’t afford the two-hour commute to Lohardaga where her parents, two brothers and three sisters live. The family survives on the income of her elder brother who drives an autorickshaw. Until recently, her sister worked as a sales person in a local store, but lost her job after she took ill. She, too, used to participate in district-level tournaments, but gave up upon seeing Dipti’s struggle.

Past days of glory

Back in Lohardaga, Dipti’s mother Sita is happy to reminisce about the ‘glory days’. In this three-room house too, certificates, trophies and medals adorn the walls and shelves. Sita is only 45, but years of poverty and disappointment have taken a toll on her health.

“I used to work as a labourer to help Dipti. When my body did not support me, I begged people for money,” she says. Every time Dipti participated in tournaments in other cities, Sita would give her Rs 100.

“She played so well, and would come home with a medal every time. We used to think that when she makes a name for herself, our condition would improve,” says Sita.

Dipti’s youngest brother, a teenager, still dreams of becoming a national-level archer, and is currently playing at the state-level. In early January, he returned from a tournament in Rajasthan. He wears Dipti’s old tracksuits.

“You took those tracksuits I like. I also had to wear them,” he tells Dipti.

“I will get them back when I come again,” she replies calmly.

Also read: From bamboo bows and arrows to World No 1 — The remarkable journey of archer Deepika Kumari

Big promises, small hope

Dipti learned archery from a school teacher, and enrolled herself at the Tata Archery Academy in Jamshedpur.

“I introduced archery to my cousin, Deepika Kumari,” she claims. Deepika, who is from Ranchi, is currently placed 24 in world ranking (of recurve women). In 2012, the year Dipti missed out in Utah, Deepika reached No. 1 ranking in the world of archery and regained the top position in 2021.

“We would practise whole night. I am happy for her that she got a job as well as a name. It is her hard work,” Dipti says with grace and dignity.

On 23 January, for the first time, Jharkhand Chief Minister Hemant Soren presented appointment letters to 27 sportspersons—17 women and 10 men—under the state’s sports quota for government jobs. Four of them were archers. All the successful candidates will now serve as constables in Jharkhand Police. Dipti, too, had applied but wasn’tselected.

“Those sportspersons who have not received appointment letters should not be disheartened as the government is working on an action plan for all of them,” CM Soren had said at the ceremony in Ranchi.

In September last year, the state government rolled out a new Jharkhand Sports Policy 2022, aimed at “reducing bottlenecks from the path of sportspersons”. But Dipti has not benefitted from it.

“The government says that it will give jobs to national and international medal winners, but in the policy, it has been made clear that jobs can be given only to those people who have won international medals and have been recognised by the Indian Olympic Association,” a source in the sports ministry told ThePrint. Dipti does not meet the criteria because she has won no international tournaments.

While launching the policy, CM Soren admitted that many sportspersons in Jharkhand win national and international competitions with limited resources.

Dipti pulls out a letter signed by Sanjay Seth, BJP MP from Ranchi. Dated November 2022, Seth promises that the government will equip her with a bow.

But so far, the gift remains elusive.

“As of now we do not know anything about it. If it comes to our notice, we will definitely do something,” says Jharkhand sports minister Haifizul Hasan.

All Dipti can do now is wait.

“I am hopeful that the government will help me. I am not begging for anything. I have talent and I can do something for my country. All I need is a little support,” she says.

Whorls and wisps of steam rise from the boiling pot of tea on the stove. As she tends to it, Dipti looks out on the road. Vehicles of many leaders and senior officers pass her stall every day, but no one ever pays attention to her.

(Edited by Prashant)