New Delhi: While browsing the aisles of Hopscotch Reading Room, a Berlin bookstore known for its non-Western titles, Arshi Javaid spotted a spiral-bound collection of stories. It was small, simple, and powerful. A writer herself, she asked the shop-owner if her work could take the same form.

But when the Kashmir-born academic set about the task, a friend stopped her, saying her stories could sustain an entire book—one that captured her memories of Srinagar, the city she calls home.

Within a week, Javaid was reaching out to publishers. That was the start of Yaadgah: Memories of Srinagar, a collection of essays dedicated to the old city and its changing landscape, edited by Javaid.

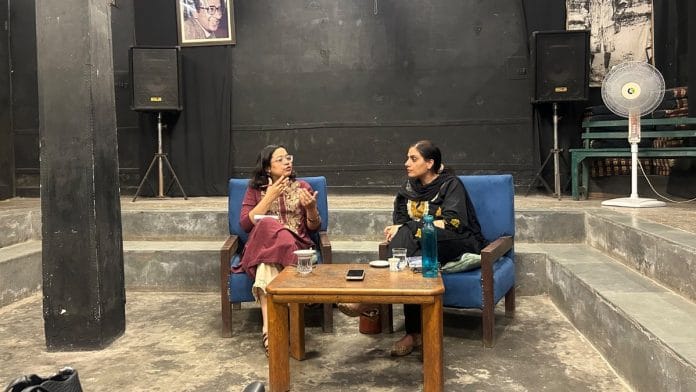

“I was a little scared to bring these stories to work, unsure if they carried any meaning or weight. But Ishita, one of the editors at Yoda Press, responded immediately, and that’s where my confidence began,” Javaid said at the launch of the book on 31 August, in conversation with historian and multidisciplinary researcher Ekta Chauhan at Studio Safdar in Shadi Khampur. “There are so many yaadgahs [remembrances] inside me.”

The project moved quickly. Javaid, who was pregnant at the time, wanted it underway before giving birth. Within a few months, as Javaid welcomed her daughter, a small book was also born, one that brings out bittersweet memories of a multicultural Srinagar where Kashmiri Muslims and Pandits co-existed.

She said the book grew out of her “knack for storytelling,” a trait she claimed most Kashmiris inherit from their grandmothers, who pass down folklore with vivid imagery. For her generation, she added, the seed of storytelling was sown during long power cuts and in the “darkest hours” of militancy. The launch itself was intimate, with a small audience of academics listening to the conversation.

“Srinagar lies at a horrible intersection of capitalism and politics emerging there. The social fabric has completely changed and I miss Srinagar where I was born and I was raised,” she said. “It’s the memory of Srinagar which keeps on haunting me.”

Also Read: The Untold Kargil Story—100 Bofors guns, satellite phones, and ‘did Musharraf tell Sharif?’

The changing social fabric

The conversation turned to how Srinagar has transformed in the past few decades through political turmoil and then a new push toward infrastructure and modernisation.

“Suddenly that social fabric has just evaporated,” Javaid said. She recalled neighbourhoods where everyone knew each other and children played in the streets, until everyday life was reshaped by “State restrictions”.

She pointed out that in Kashmir, privilege has always been tied to political influence, but these equations were also upended after the abrogation of Article 370.

“What we saw in 2019, they overturned the political elite cultivated over the years in a single stroke.”

Now, public life looks different. Social media influencers can be seen dancing in mosque compounds, she noted, using them as mere scenic backdrops. A beloved bookshop called Gulshan Books—once a haven for readers—was forced to close this year; its owner, according to Javaid, plans to repurpose the space into a shop for handicrafts and dry fruits.

Yaadgah, she said, is her way of holding on to what is slipping away, of preserving fragments before they vanish.

“It’s an urgent appeal for those of us who could preserve whatever they can from memories, talking about these memories, articulating it, taking it to the next generation,” she added.

Also Read: Business-politics nexus benefited Congress first and then BJP, says Mani Shankar Aiyar

Representing the city’s fracture

In one chapter, ‘Ragini: The Story and the Storyteller’, Javaid writes about a woman in her mid-20s from Habba Kadal, a neighbourhood where most Pandit families migrated but hers stayed behind. The reasons were unclear—perhaps a sick grandparent, perhaps financial strain, maybe both. Ragini grew up feeling betrayed “by the community that left, by the state, by the Army.”

She spun stories around herself, imagining an escape into another life. Once, she told Javaid, “I was in a temple, and I was singing there. Ismail Darbar heard me singing, and he said, ‘you should come to Bombay, I will take you to Bollywood’.” At other times she dreamed of marrying a rich man to break free from poverty.

Today, Ragini lives outside Habba Kadal, a move she takes pride in. She described the old neighbourhood as carrying a “strange smell… like when open drains get green mould”. After leaving, she noticed her hair no longer carried that odour. Instead, she spoke excitedly about new shampoos and hair highlights she wanted—ash-coloured, like the women she saw in wealthier areas.

Despite being a graduate, Ragini has not been able to find steady work. Javaid noted that she struggles with health issues but resists treatment. “She’s a reminder of everything that was troubling Srinagar,” Javaid said.

During the conversation, Javaid said that Ragini embodies the fractures of Srinagar city including its class segregation, uneven opportunities, and the burden of survival. “I’m sure there are many Raginis going around,” she said. “Maybe the stories are few, but at the core, a lot of problems actually collide.”

(Edited by Asavari Singh)