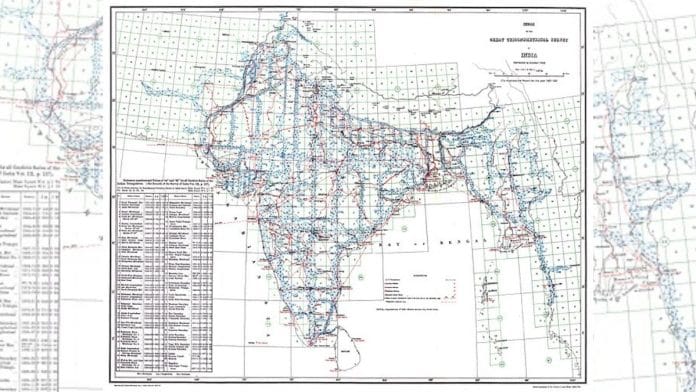

New Delhi: In the 1800s, after Tipu Sultan fell in Mysore, the British wanted to rule over South India. And they set out to do so with their age-old imperial trick: divide and conquer. Except, the division was mathematical—they split the land into several triangles to measure it using the basics of trigonometry.

The colonial rulers wanted to understand the length and breadth of the Indian peninsula. They longed for an accurate map.

During the triangulation survey, Lieutenant-Colonel William Lambton, a geographer, meticulously measured the length, breadth, height, and dip of the peninsula with his team for more than 20 years.

Lambton, who worked on the survey for 25 years, had no clue that his efforts would later be named the Great Trigonometrical Survey of India, which helped the British Raj rule and tax Indians.

It all started in Bengaluru, according to Jahnavi Phalkey, a science historian and director of Science Gallery Bangalore (SGB). But the origin story is coloured by a dispute with the measurement activity in Chennai.

A Bengaluru ‘benchmark’

An out-of-sight marker at the Mekhri Circle Park in Bengaluru, the highest point in the city, tells the tale of the great survey, which even led to calculating the height of Mount Everest—named after George Everest, who was Lambton’s successor in the survey.

The stone in Mekhri Circle, upon closer inspection, reveals in thick font that the survey began in Bengaluru: “GTS BM” (the Great Trigonometrical Survey of India, Bench Mark).

Not everyone agrees. Was it Chennai (formerly Madras) where the survey began?

While historians such as John Keay noted that the survey officially started in Chennai, there are reports suggesting that the first practical baseline measurements were taken near Bengaluru in the 1800s.

“It was definitely Bangalore. They needed to understand how to create a baseline, and so they did that in Bangalore. After that, they moved to Chennai and started work from there,” confirmed Phalkey, who was involved in verifying documents as part of SGB’s exhibitions that showcased scientific achievements that occurred in Bengaluru.

The confusion was in distinguishing between two years of baseline work in Bengaluru that started in 1800, and the official survey measurements and systematic operations, which began in Chennai in 1802.

Phalkey was helped by Arun Pai, founder, BangaloreWALKS, to find documents that stated the role of Bengaluru in the survey.

“It is very logical that if you are doing a mapping of a continent, you will find the meridian first. Set the meridian in place, and then everything is referenced to the meridian. And so that’s why they chose (Bengaluru),” said Pai. Bengaluru offered a natural reference point along the geometric meridian arc that divided India almost symmetrically.

His recent Instagram video, in collaboration with SGB, where he takes the viewer from survey points in Mekhri Circle to the SGB exhibit, has more than 1 lakh likes.

Wikipedia mentioned Chennai as the origin point, before the entry was corrected. “Wikipedia is not always right. So I have spoken to the editor of Wikipedia and said we need to put all these facts out there. Eventually, Wikipedia has changed,” said Pai.

Lambton picked a place which was east of Bengaluru to find a reference point that relates to a zero point, according to Pai, who has sifted through historical documents. Lambton referred to it as Dodagoontah (today’s Cox town) Meridian. (Deccan Traverses: The Making of Bangalore’s Terrain by Anuradha Mathur and Dilip da Cunha).

“The Bangalore Base Line, the first base line drawn by Lambton, was drawn on a flat stretch of (nearly) 7.5 miles. He chose a point near today’s Ramamurthy Nagar as the start point, and went south till Agara for the end point. The triangle was completed at the Muntapam Hill (today’s Mekhri Circle),” noted Pai in an email to SGB as a response to the Chennai-Bengaluru origin dispute that followed after his video.

The book, Historical Records of Survey of India, Volume 2, notes that the first survey began in Bengaluru, and around 7 seven miles were measured in 57 days in 1800.

Around the 1800s, when Tipu Sultan lost his territory in the fourth Anglo-Mysore war, the British wanted to take control of the port. Lambton, who was in the army, was assigned to map the distance from (then) Madras to Mangalore. As a mathematician, he knew that for any measurement, a convenient and accurate reference point was needed.

As a coincidence, the reference point fell at a place which was east of Bengaluru.

“Lambton could have started in Madras in 1800 if he wanted. He was anyway based out of there. Why did he come to Bangalore to start his experiments? That’s the first question I ask people who dispute it. There was a reason that he started in Bangalore. And the reason was, it was right in the middle, along this meridian which he said was the right way to measure. He had identified that meridian (in Bengaluru),” Pai wrote.

The error begins with Keay and continues down the line.

“The trouble is that common sources like Wikipedia and John Keay’s popular book don’t mention any of the pre-Madras work, and so most references start from 1802,” Pai added.

Previous and contemporary efforts to survey the Indian peninsula were to walk all along and measure footsteps. But Lambton, who had mathematical insights, decided to apply trigonometric theories.

His tools were of two types: a ruler and a theodolite. A theodolite is used to measure angles of elevation and dips.

Also read: Delhi’s smog is back. Here’s how GRAP kicks in to control it

Divide and measure

The whole survey was done through triangulation. The method locates reference points, usually hills or tall buildings. The exact distance between these two points and angles made by their sight lines to a third point are measured, thus forming a triangle.

The distance and position of this third point can then be established using trigonometry, which helps calculate unknown distances based on known angles and distances. This newly determined third point then becomes the base for the next triangle, and the process is repeated until the mapping completes.

However, measuring the distance between points was easier said than done. It was affected by temperature changes and even small elevations on the ground.

“Lambton was deeply concerned; measurements and readings were to be taken only at dawn or in the early afternoon, when the temperature was as near stable as it got. The thermometers were checked and rechecked, both chains measured and re-measured against a standard bar. Nothing gives a better idea of his passion for shaving tolerances to an infinitesimal minimum than this pursuit of a variable amounting to just seven thousandths of an inch,” Keay wrote in the book, The Great Arc: The Dramatic Tale of How India Was Mapped and Everest Was Named (2000).

For distance measurement, a foldable ruler—that looks like a chain—was used.

“Forty bars of blistered steel, each two and a half feet long and linked to the next with a finely wrought brass hinge, the whole thing folded up into the compartments of a hefty teak chest for carriage. Thus packed it weighed about a hundredweight. Both chain and chest are still preserved as precious relics in the Dehra Dun offices of the Survey of India,” Keay noted in The Great Arc.

Many lost their lives, and some became scrawny during the survey, exposed to tropical diseases such as malaria. It took around 100 years to finish the undertaking.

Lambton, however, was not celebrated much. He breathed his last in Nagpur during the course of the survey and is buried in Hinganghat behind a slum. The grave is not well-maintained, Keay wrote in his book.

The survey was the greatest mapping effort done until the 1800s.

“Mapping was an integral part of the colonial expansion into India. As you mapped it, you knew what was going on. So that’s how colonialism worked,” said Pai.

(Edited by Prasanna Bachchhav)