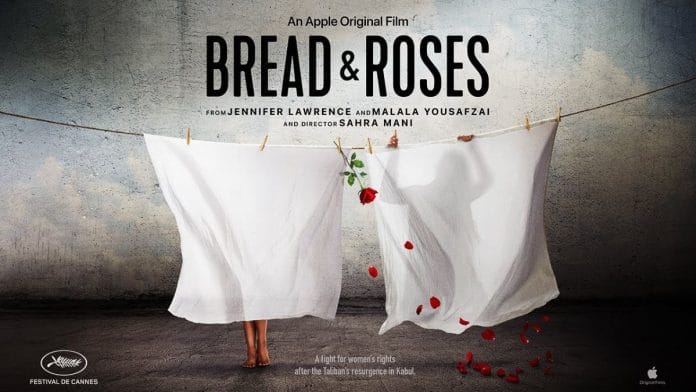

New Delhi: Under a pale, oppressive sky, a barren field enclosed by barbed wire serves as the haunting final scene of the documentary film Bread & Roses. The scene is a metaphor for the lives of Afghanistan’s women: a life stifled, dreams fenced in, and resilience rooted in infertile ground.

The film is directed by Sahra Mani, an Afghan filmmaker and film professor at the University of Arts London and produced by Justine Ciarrocchi, actor Jennifer Lawrence and activist Malala Yousafzai. The film is the first one made in Afghanistan after the fall of Kabul in 2021. It captures the lived, unfiltered realities of countless women who have been fighting for life and fighting to death. As a former lecturer at Kabul University who managed to leave the country before the Taliban takeover, Mani asks a fundamental question: Why is something as basic as bread so costly that families are forced to sell their children to buy it?

“The Taliban fear educated women because they raise empowered future generations. The Taliban radicalise young men to recruit them as soldiers. They don’t want human civilisation, and this should alarm us all and make us stand with Afghan women,” Mani told ThePrint.

The recent ban on medical courses for women highlights the documentary’s urgency—a call to action against the systemic erasure of women and their rights in Afghanistan. In Taliban’s Afghanistan, even bread—a symbol of sustenance and life—has become a harbinger of despair. “The bakers carried bread in coffins,” narrates the film.

Also read: Afghan women didn’t want to seek refuge in India—They hardly had other options

Naan, Kar, Azaadi

There was a time in Afghanistan when women were visible in politics, media, and education, when they could be seen wearing colours and when normal life was in motion.

“Despite the fall of Kabul, we never lost faith because we know oppression and dictatorship can’t last forever. Through unity and collective action, we can overcome it all,” Mani told ThePrint.

Mani had been working with a charity supporting at-risk Afghan women and received raw footage from these women, which is used in the film. Many had lost their jobs and their rights and were struggling to survive under the regime, yet they continued to film their protests — some even risking their lives to spray anti-Taliban graffiti on Kabul’s streets.

“I trained several protagonists to film their lives. Emotionally, I lived with them and with all the women of Afghanistan. I wanted to represent their story in a way that people could not just see but feel, to truly understand and even smell the situation,” she said. Her team gathered cell phone footage, archival materials, and voiceovers to bring the women’s voices to life.

The documentary opens in 2021 with the return of the Taliban and the eruption of women-led protests against the harsh restrictions imposed on them. Under Taliban rule, women are barred from travelling without chaperones, wearing makeup, dancing, singing, or even listening to music.

The film features Zahra, Sharifa, and Taranom, the three protagonists who are now rebuilding their lives outside Afghanistan. Zahra, a dentist, was forced to take down her clinic’s signboard simply because it displayed her name.

The experiences of these three women are not unique, Mani connected with over 80 women to ensure the story’s authenticity.

Some mothers were the sole breadwinners for their families. They were forbidden to work, yet still had to find a way to feed their children. “I had five protagonists, two of whom were mothers dealing with more extreme hardships,” Mani said. “But I ultimately chose three young, educated, and modern women. I wanted to show that these women, with all their talent and education, are ready to contribute to society and build a future. Yet they remain prisoners within their own homes, unable to do what they know they can.”

Also read: Taliban makes women unsafe everywhere. ‘Not as bad as in Afghanistan’ is now a dangerous tool

A quiet defiance

In one of the scenes of the documentary, a woman visits a protagonist’s home, bringing music with her—an act of defiance and a rare privilege for these women. In another moment, a woman teaches her mother how to write, a quiet rebellion against the oppressive environment. Meanwhile, the men insist that the women must stop attending protests, warning that their activism disgraces the family.

“I fight for freedom during the day and get beaten up at night by Talibs,” says one of the protesters in the film.

Mani said that local artists and filmmakers are the best equipped to address the pressing issues of society, from taboos to societal norms, without judgement. “Storytelling is about sharing emotion and experience, and I wanted my audience to truly grasp the weight of living in such circumstances,” she said.

For her, this is the power of cinema. She sees documentary filmmaking not just as a medium for storytelling but also as a tool for education—an opportunity to spark discussions and provoke thought on the injustices people face.

A particularly moving moment in the film features a woman sharing her poetry:

“Damn, a bad mood, and a bad year and loneliness.

And spring, which is a torment, where are you without me?”

This talent, constrained by the harsh realities of life under Taliban rule, resonates deeply with Mani. “In my language, Farsi, we have such a rich history of poetry and music. We grew up in families where we read poems, gathered to read, sang, and even danced. This is in our blood,” she said.

Even under the extreme conservatism of the Taliban, she has faith in the enduring power of art. “We kept the poetry and literacy alive. It’s part of our daily life, a reminder that art, literacy, poetry, civilisation, cinema, and music are the true winners,” she said, highlighting the unyielding spirit of Afghan women.

Mani and her team aim to screen the film for UN organisations and global decision-makers. “We hope this film can bring change, help women in Afghanistan reclaim their human rights, and hold onto the rights they deserve,” she said.

Inspired by both the new generation of Indian filmmakers and the legendary Satyajit Ray, Mani admires the level of education and talent in Indian cinema. She wants to collaborate with Indian filmmakers and one of her greatest aspirations is to visit Ray’s home and the locations where he filmed. “I’ve watched Ray’s films more than ten times. His work is a deep inspiration to me,” she said.

While she’s drawn to cultures close to her roots, such as Tajikistan, Mani feels no pull toward working in Europe or the US. “I want to connect with cultures that resonate with me, not just for the sake of making films, but because they are part of my soul,” she said.

For Mani, art is a unifying force. “Artists should be close together; more than politicians,” she said.

(Edited by Theres Sudeep)