Bengaluru: Bengaluru resident Onkar Chopra wants to tackle the traffic problem. Not on the infamous Silk Board junction or Hebbal flyover, but in the skies above. The aerospace engineer is preparing for the day when drones will be buzzing around in droves.

“All these drones will exist in the shared airspace. There needs to be something that can coordinate their flight to avoid any conflict and catastrophe among them,” said Chopra, co-founder and CEO of AlgoBotix, a drone startup focusing on traffic management.

He’s betting on India’s drone market that’s projected to hit $11 billion by 2030. And AlgoBotix isn’t the only startup to do so. Another startup incubated at the Indian Institute of Science (IISc) in Bengaluru has developed a power amplifier that can help drones transmit signals over a much wider range. One Bengaluru startup is also developing operating systems to secure drones from any foreign threats and hacking.

Today, most of Indian airspace — up to 400 ft — has been designated as a green zone for private players to operate drones without special permission. The Indian government has also recognised the potential of drones in farming and other related activities. And after Operation Sindoor, the role of unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) in surveillance, emergency response, and national security has come sharply into focus.

What has given entrepreneurs and engineers the impetus is the collective realisation that India cannot be solely dependent on other countries for the technology. At present, around 40 per cent of flight controllers used in Indian drones are imported from China.

Now, there’s a push for homegrown innovation from the Centre to the grassroots.

“We have to have strategic autonomy in drones because we cannot really continue to depend on imports for our needs,” said Commander Syed Qais Hayat (retd), head of defence innovations at IISc’s AI and Robotics Technology Park (ARTPARK). He is also an ex-commanding officer of the Indian Navy’s indigenous weapon platforms.

“The core of the challenge is we have not invested adequately in indigenous development of technologies which are required for advanced Unmanned Aerial Systems to perform,” he added.

Managing drone traffic

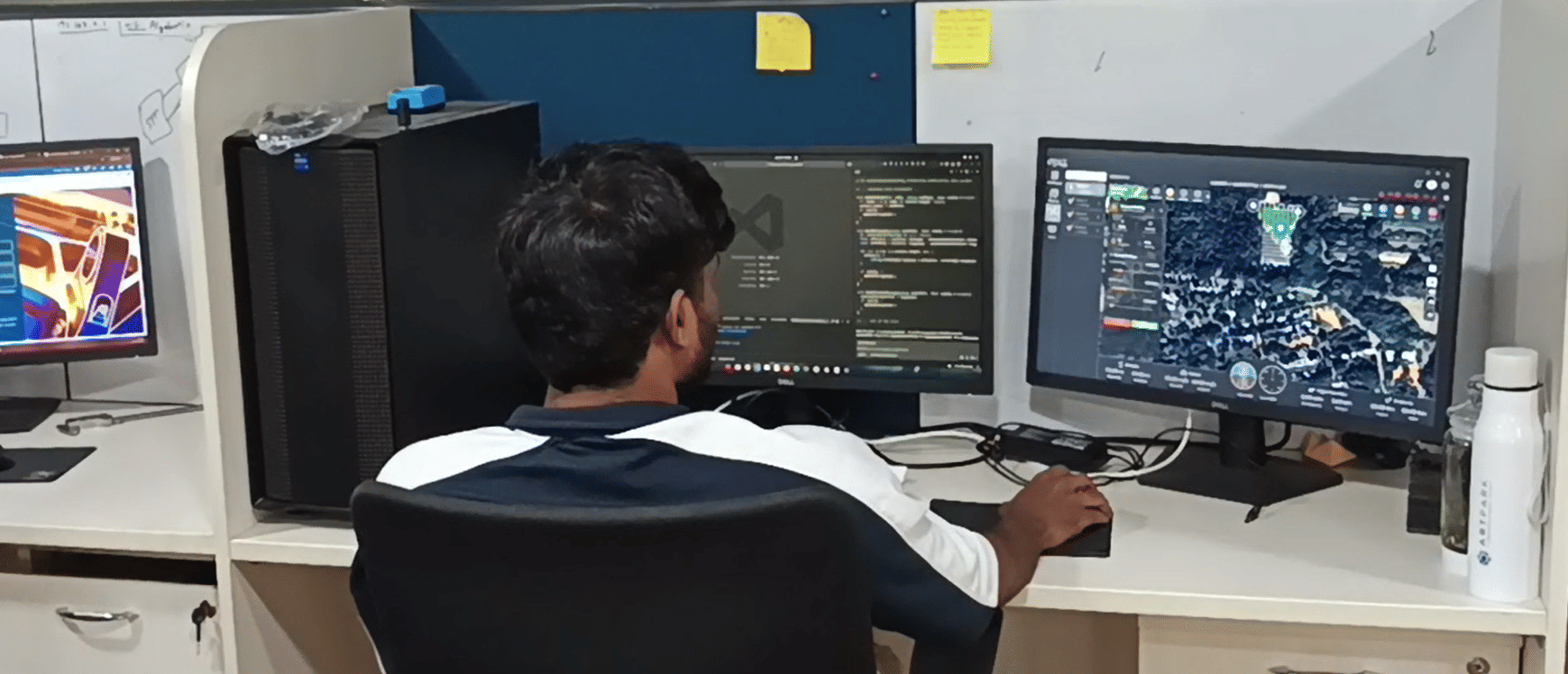

At the ARTGarage Incubatory near the IISc campus, Chopra and his six-member team are building a virtual model of a drone corridor to ease traffic. The manufacturing and testing facility for robotics and autonomous systems has everything they need.

The AlgoBotix team carefully draws boundaries over a green patch on their computer. It resembles a map to guide a virtual drone to follow the desired path while flying.

At present, the drone technology exchanges data with Air Traffic Controllers. That said, the present system has pitfalls such as privacy concerns and autonomy. So, Chopra’s team is interested in path-optimised mobile corridors in the shared airspace with specific boundaries for the drones.

“If a drone stays inside those corridors, then there is a guarantee of no conflict. So the drones need to communicate with the central command station, which will be responsible for a large number of drones that are managed in that particular airspace,” said Chopra.

According to the founder of the two-year-old start-up, backed by the Karnataka government and the Department of Science and Technology (DST), their system will raise an alert if any drone breaches the boundary of its corridor, and flag the breach to the operators in the same airspace. The team has tested their management system with around five drones that flew around 50 minutes at their testing ground in ARTGarage.

“Now we have to expand these boundaries. We have to bring more players into the ecosystem involving at least some 30 drone manufacturers and then several kilometers of airspace is to be planned,” said Chopra.

In India, the number of drone use cases will be in proportion to the country’s population, Dhavala Sai, business team lead at AlgoBotix, told The Print. As a densely populated country, the massive use of drones calls for a secure traffic management system.

“People have so many drones purchased already, they would definitely make it fly. If there’s a space which is not regulated and no official software which can handle multiple drones altogether, it could be even more scary,” said Sai.

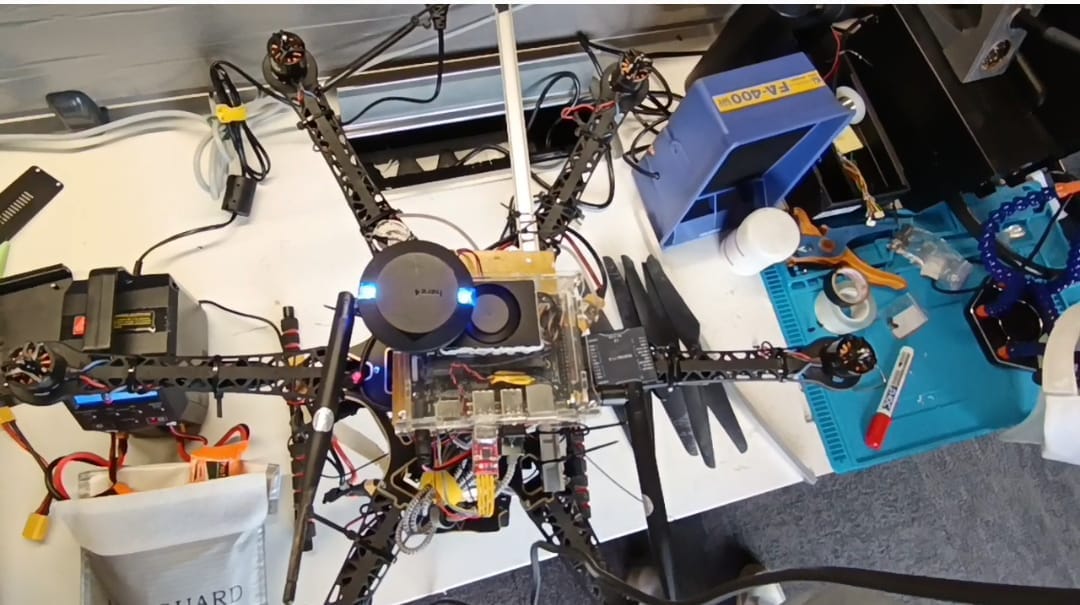

One of the drones used to test the traffic management system by AlgoBotix was from a drone manufacturing startup, COMRADO Aerospace, housed in the same garage where work on Chopra’s traffic system is underway.

The 36 people in the COMRADO team are building drones from scratch in their massive garage the size of three football turfs. It’s not the most aesthetic workspace — with grease, propeller parts, and motors scattered around. Co-founder and CEO Ansar H Lone calls it the “dirty space” where most of the work happens as they test their variety of motors.

In another corner of the room, a team is assembling the engine and parts of a vertical take-off and landing (VTOL) drone.

“The drone technology is maturing at such a speed that the cost is going down drastically. The moment drone tech becomes accessible to all, our skies are bound to be filled with them,” said Lone.

Although Lone’s team mostly focuses on military applications, they are also working on drones for agricultural purposes like spraying chemicals on tall trees.

At COMRADO, while the manufacturing is outsourced to other players in India, almost all things that go into the drone are designed in-house.

Both Lone and Chopra say that indigenous development of drone components is a pressing need. Chopra is wary of the risks of hacking into the drone traffic system and suggests end-to-end encryption.

Also read: Just protecting borders from drone attacks isn’t enough. Look at Ukraine & Russia

Homemade chips for drones

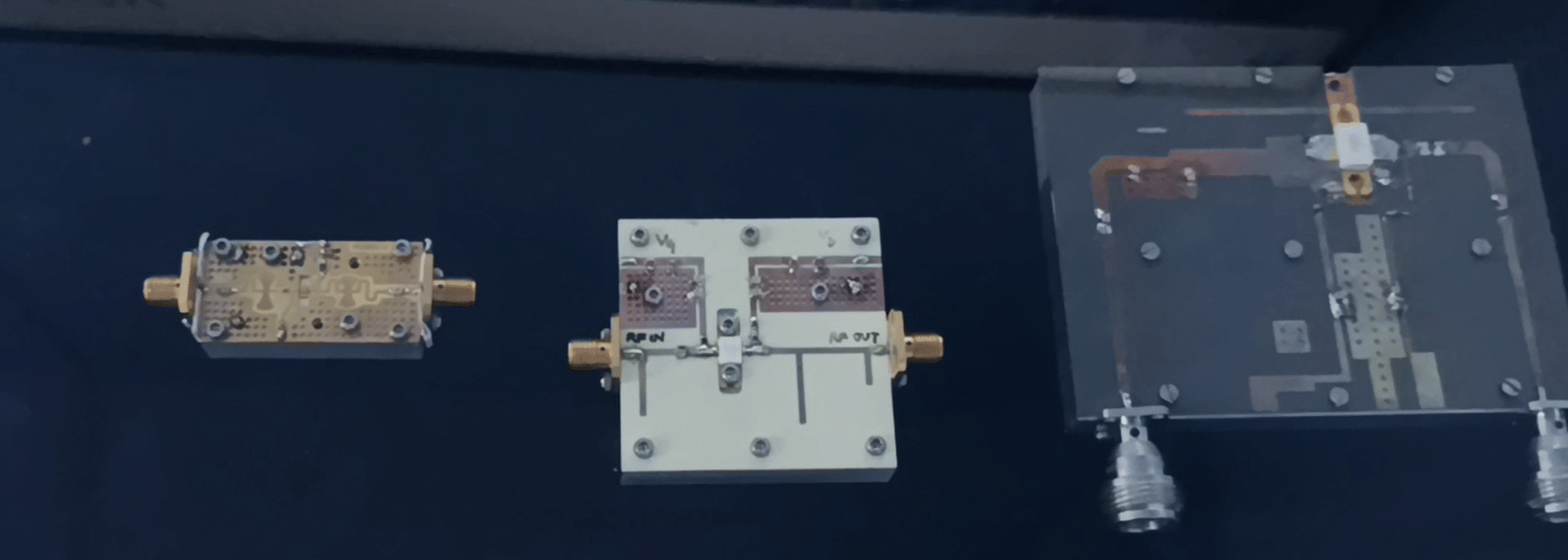

In 2019, when Hareesh Chandrasekar, a semiconductor engineer, teamed up with eight academics at IISc to start a semiconductor startup, he did not foresee helping drone companies secure their communication. Five years later, a client approached his company, AGNIT Semiconductors, with an unusual request.

The client wanted to use a gallium nitride (GaN) power amplifier instead of a conventional device to increase the range of the communication used in their drones.

In silicon–based power amplifiers, the range of communication is limited. Incidentally, the team was also working on GaN to use it for amplifying power for better communication in devices. “It took us about six months to develop and more importantly we had to test it,” said Chandrasekar, co-founder and CEO of AGNIT Semiconductor, which was incubated at IISc’s Centre for Nanoscience and Engineering (CeNSE).

A power amplifier is a hungry device that consumes a lot of input power in an electronic system. The GaN power amplifier is much more efficient than conventional solutions in the market.

“Fundamentally, the material properties of GaN are superior to that of silicon. It can block higher voltages, it can switch faster, it can also give higher current. All of this basically ensures that you can get higher power, you can get higher efficiency, better heat management,” said Digbijoy Neelim Nath, co-founder and CTO of AGNIT semiconductors.

Also, the GaN is compact and sits easily without disturbing the balance of the drone. Although the power amplifier is indigenously made, Nath is also aware that there is a supply chain problem when it comes to large scale indigenous production of devices, since almost all the tools and chemicals are imported from abroad. The chemicals used to fabricate such power amplifiers have to be pure. India does have most of the chemicals, but the country lacks the methodology to purify them, according to Nath.

“Without this supply chain being in-house, we are always at a risk. We may have all the know-how of design and manufacturing and packaging of semiconductor chips. If the equipment and chemicals have to be imported, then technically we are not independent,” said Nath.

Most of the semiconductor chips used in drones can be bought from commercial players. But such chips are susceptible to electronic counter-warfare.

“Electromagnetic Fault Injection Attacks can take over drones remotely and alter their paths. Thus the need is to make radiation-tolerant chips and special communication chips that can tackle electronic counter-warfare,” said Pranay Kotasthane, deputy director and chair of the High Tech Geopolitics Programme at the Takshashila Institution in Bengaluru, and also the co-author of the book When the Chips are Down.

But drone tech entrepreneurs like Chopra see a different side to supply chain hurdles. “Even though the chips are imported, but if they are programmed indigenously. Then that is not a threat,” he said.

Also read: Make in India is a startup graveyard

A case for indigenous OS

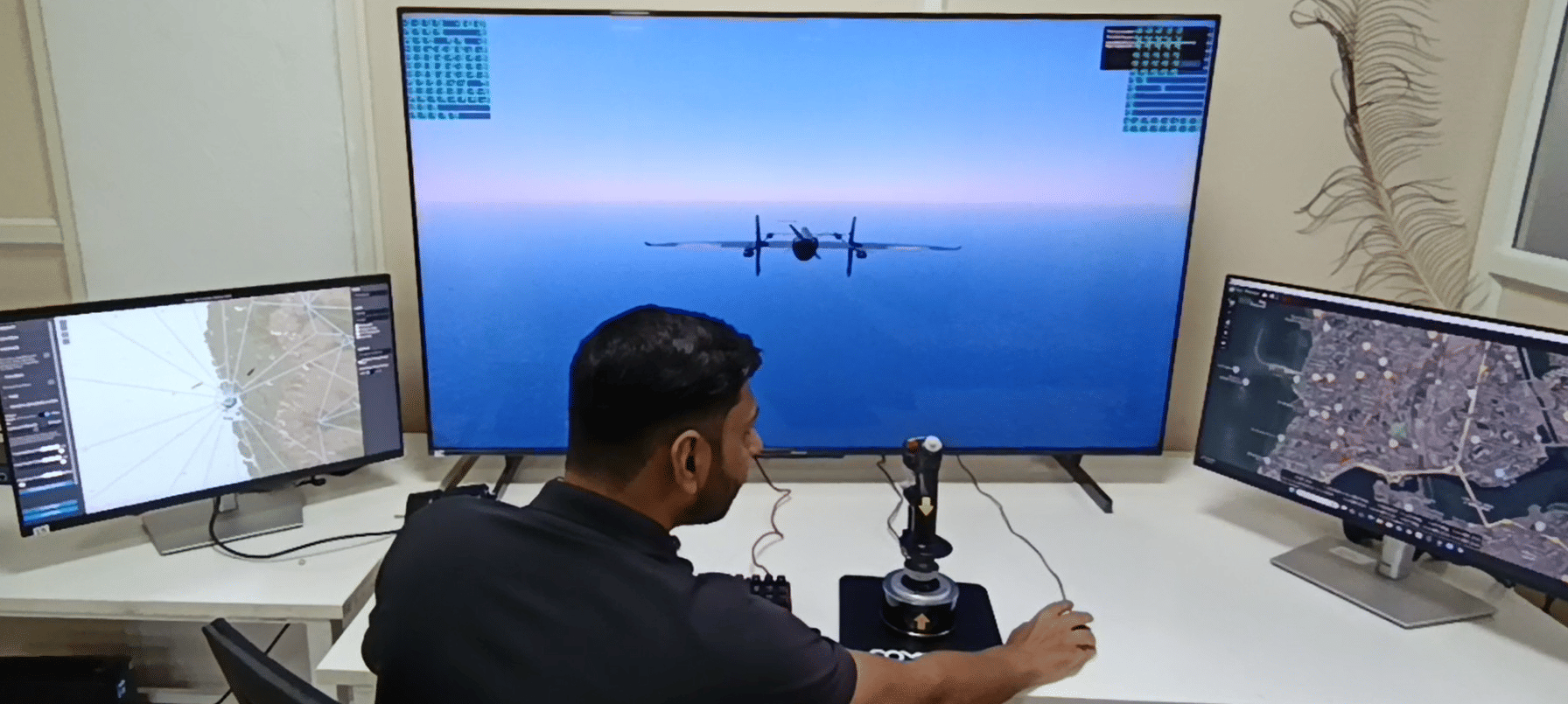

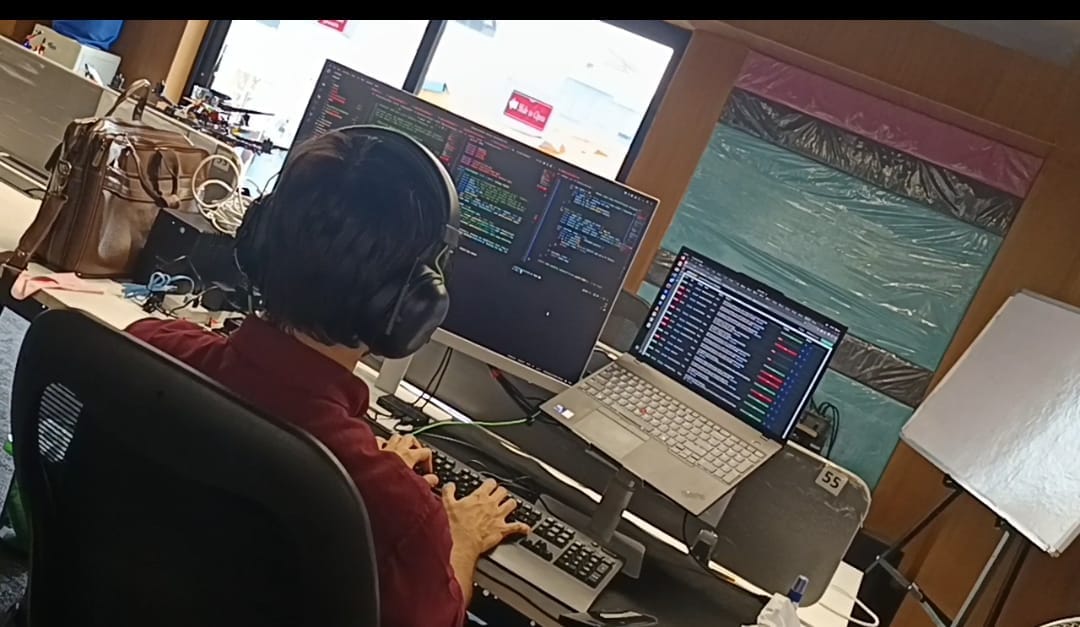

During his conversation with stakeholders in the defence sector, tech entrepreneur Shitiz Bansal realised that the market lacks software for the existing hardware. In 2024, he launched his company Vyom OS along with his IIT Delhi batchmates.

At Vyom OS, the team is trying to build operating systems similar to Windows and Android so that drone developers can use customised software tailored to their specific needs.

The team uses programming software like Python and C++ to build a middle-level operating system for drones. “We need to have the code built in India,” Bansal said.

Security is the top priority. More than 10,000 agricultural drones already deployed across India mainly rely on Chinese software and hardware, he explained.

“Somebody shouldn’t be able to hack into your devices to remotely control (the drones). The more control that you have over your software stack, the more control you have over your future security,” said Aditya Agarwal, co-founder, Vyom OS.

The brain of the drone that has access to camera and other critical components can be firewalled with a strong operating system.

“So, working with more sophisticated hardware (like the chipset) paradoxically actually gives you more control over the entire drone,” he added.

As the Indian deep tech industry is gearing toward a self-reliant drone system, entrepreneurs like Agarwal, Chopra, and Lone are expecting the market to support the growth of indigenous drones in India. Nevertheless, there are bottlenecks in the basic research and development system.

“We need to have our own R&D ecosystem, our own IPs, and innovation pipeline in this segment. And we really need to be mindful of the risk that we get exposed to when operating imported drones,” said Cdr Qais.

The real challenge, he explained, is bridging the gulf between readiness level three and seven of a technology’s evolution. It’s only at the seventh level that technologies are mature enough for the venture capitalists to step in.

As Cdr Qais puts it, the innovations should move beyond prototypes to finished products through grants by the end user. The grants should support the development until the commercialisation stage is reached, so that early-stage startups do not stall before their products become commercially viable.

“Nobody is going to make drones which are customised specifically to our requirements. We will have to innovate to solve our own problems,” he said.

(Edited by Aamaan Alam Khan)