New Delhi: The Statue of Unity in Gujarat will soon open an exhibition on the various princes who played a role in the integration of India, Karan Singh, former minister, and titular maharaja of the princely state of Jammu & Kashmir said at the inaugural lecture on ‘Life and Times of Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel’, a series of lectures organised by the Centre of Contemporary Studies.

At the Prime Ministers’ Museum & Library auditorium, Singh, 93, drew from his own experiences of meeting the architects of modern India in his youth and childhood. The audience maintained pin-drop silence as they heard what he had to say.

“Patel’s most historic achievement was the integration of the Indian state, and a peaceful transition of power from feudalism to democracy,” Singh said, “But it was the good patriotism of the princes and royal families as well that led to a smooth integration of India, I have been told the Statue of Unity will soon have a museum, which will show the prince’s contribution. Some justice will be done to the princes’ role as well,” Singh said.

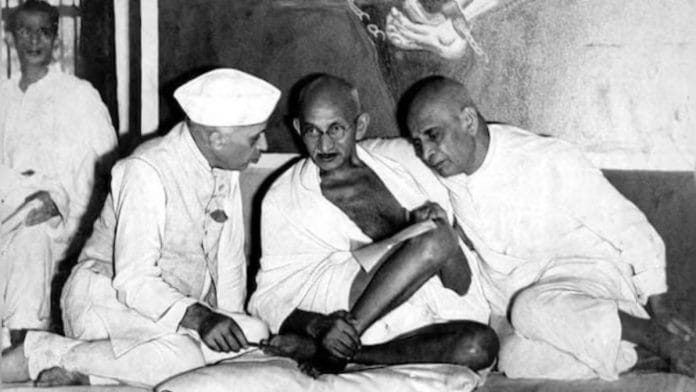

Singh said that former UK Prime Minister Winston Churchill’s prophecy that India would ‘break into 20 pieces’ after Independence would have proven true if not for the leadership of Patel and Jawaharlal Nehru. “Nehru led the left of Congress and Sardar led the right. Patel brought stability and Nehru brought charisma. Without the two of them India wouldn’t have survived Partition,” Singh said.

Also read: How Nehru became Congress president over Sardar Patel—diary entry sheds new light

Gandhi’s pick

Singh kept his lecture short and sweet and mostly drawn from his personal interactions with Patel. Singh, who married Yasho Rajya Lakshmi, princess of Nepal, said that Patel might have had a hand in ensuring their rishta.

“Sardar wanted cordial India-Nepal relations, and I think he spoke to my father about it. I was engaged to be wed but that engagement broke, and my father hitched me to the princess of Nepal. I think he was responsible for me finding my wife!” Singh said.

Patel played an integral role in Singh’s life since his childhood. When Singh was bound to a wheelchair as a child, it was Patel who told Raja Hari Singh to send him to the US for treatment. “If not for him, maybe I’d have been in a wheelchair even today,” he said.

Singh’s introduction by, Nripendra Misra, the chairman of the executive council, Centre for Contemporary Studies, was longer than Singh’s lecture on Patel.

Over 15 minutes, Misra talked about Singh and his achievements in great detail. “Dr Singh is a representative of true Vedantic heritage, he is well versed in the knowledge of Sanskrit, well known for his ingenious ideas, and the revered son of Hari Singh,” Misra began, and went on to call Singh the “Raj Rishi of our times”.

The Sanskrit language was given centre stage during the event, even though the event in itself had nothing to do with the language.

Singh was presented with a plaque in Sanskrit that read out a list of his achievements, and the event was concluded with the recitation of a Sanskrit verse.

In the middle of the event, Patel found some space. Singh, who called Nehru his mentor, said that Patel and Nehru were handpicked by MK Gandhi to lead the country, and “Gandhi led well”.

After the short lecture, the audience was invited to ask questions. One of the first questions was hypothetical— “What if Patel had been Prime Minister instead of Nehru?” Singh refused to speculate.

“Eight out of 11 Congress committee members had expressed their desire to see Patel as the Prime Minister. But Gandhi knew we needed a charismatic man to lead the country. He chose right,” he said, “would Patel have changed India’s bureaucratic structure if he had been PM? I don’t know, but Gandhi’s choice was correct. Nehru’s socialist policies were needed to take care of poverty then. And the industries set up then are the heavy-duty industries of today,” he added.

Another audience member asked why India stressed the fact that Muslims didn’t need to leave the country after the Partition.

“Despite Pakistan forming on Islamic lines, the people of India didn’t want a Hindu country. It was secular from the beginning. Exchange of population was unrealistic,” Singh concluded.

(Edited by Ratan Priya)