New Delhi: From “bhalayi ki supply” to “Maya sphere”, a group of social commentators used larger-than-life descriptions for the humble green icon on our phones —WhatsApp.

“Much like the yogic concept of Maya, where the boundaries between the knowable and the uncertain blur,” reads the foreword of The WhatsApp India Story: Inside the Digital Maya Sphere by Sunetra Sen Narayan and Shalini Narayanan, WhatsApp serves as a space where connection and disconnection coexist, capturing the duality of our modern interactions.

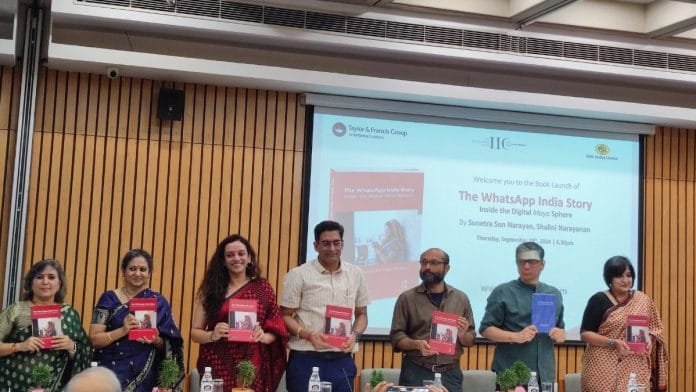

A discussion hosted by the India International Centre last month was all about WhatsApp’s profound impact on our lives. A panel featuring co-authors, Ankita Mukherji (journalist), Santosh Desai (author), Vibodh Parthasarathi (academic), Vishal Chhabra (psychiatrist), and Surbhi Pandit Nangia (VP, DataLEADS), delved into the duality of the messaging platform—how it can feel like a lifeline for some and a suffocating invasion for others.

This conversation spanned from how WhatsApp has transformed communication patterns in India and its role as a horizontal platform for social interaction to its implications for privacy and misinformation.

Also read: WhatsApp overplayed its privacy campaign—latest ad feels like a drag

Election and business

WhatsApp has proven to be a game-changer in countless ways, from boosting small businesses to energising political campaigns and social movements.

However, it has also earned a reputation as a hotbed of misinformation during the election season. Activity on the platform spikes during major political events, especially on election result days

“The 2014 elections were termed the Facebook elections. But by 2019, they were already being called the WhatsApp elections. That was the shift that happened,” Narayanan remarked, highlighting how political communication strategies have morphed in this digital age.

There was much philosophising about what WhatsApp has done to our idea of self.

“It’s almost like our default world is online, and the real world is offline,” Chhabra said, revealing the powerful influence of digital identity on our lives. “Previously the self was an internalised concept, something we held within. Now, with the rise of social media, the self has moved into an external space, the Maya sphere.”

Parthasarathi further explored this transformation through the lens of WhatsApp economies. He identified four key economies—the attention economy, which reveals patterns of addiction; the talking economy, which shows changing communication styles; the payment economy, where financial transactions blur the lines between commerce and conversation; and the surveillance economy, which raises significant privacy concerns by tracking user behaviour and interactions.

But the real power is wielded by that omnipresent, omniscient group admin.

“The role of an admin isn’t just about censoring,” Parthasarathi noted, stressing the difference between harmful and illegal content. “Not all harmful content is illegal, and not all illegal content is necessarily harmful.” In this digital ecosystem, admins serve as gatekeepers, balancing communication flow and addressing the implications of privacy and misinformation.

Nangia also highlighted tragic incidents, such as the Jharkhand lynching, where baseless accusations propagated through WhatsApp resulted in violence. She also called attention to the bizarre rumours about Covid-19.

She stressed that misinformation is a widespread issue, extending beyond media responsibility, and pointed to collaborative efforts like the Google News Initiative aimed at training journalists in effective fact-checking.

“We’ve seen cases where misinformation and disinformation have cost lives. Social media, especially WhatsApp, has led to people losing their lives,” Nangia said.

But at the end of the day, WhatsApp is us. It is only a mirror. “If there is anger, that anger will find its way out. WhatsApp is merely one medium,” Parthasarathi said.

(Edited by Theres Sudeep)