New Delhi: In a world where state-building has often involved bloodshed, India managed to emerge as a nation with relatively low levels of violence. In their book A Sixth of Humanity: Independent India’s Development Odyssey, economist Arvind Subramanian and political scientist Devesh Kapur put this down as an achievement of universal franchise—India’s democracy was a key instrument in nation-building.

“If you look at the history of state building around the world, it’s always accompanied by massive levels of violence,” said Kapur. “Building a state is to give an entity a monopoly on violence. And that monopoly is achieved by crushing other sources that could compete with the state.”

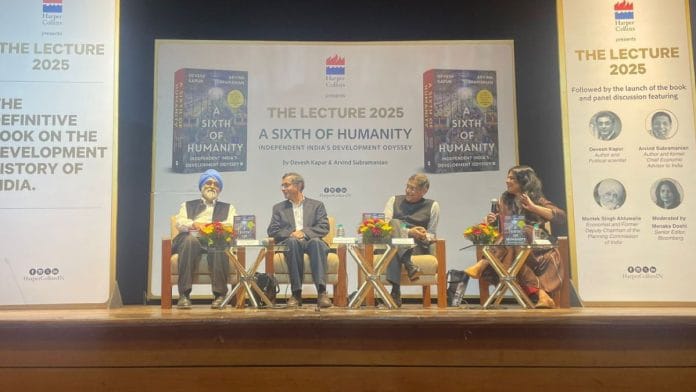

In a packed auditorium at Teen Murti Bhavan, India’s development journey—a paradox—was dissected by the authors as an outlier. After Kapur and Subramanian gave their opening remarks, aided by charts and graphs to underscore their research, a panel discussion began. The authors were joined on stage by Montek Singh Ahluwalia, economist and former deputy chairman of the Planning Commission of India, and Menaka Doshi, senior editor at Bloomberg, who moderated the discourse.

Despite early poverty, India achieved relative political order and economic stability, avoiding hyperinflation and recurrent crises seen in peers like Brazil or Turkey. “We all know of the crisis of 1965 and 1991. But otherwise, most other countries have had far more frequent crises,” said Kapur.

Fiscal federalism—financial transfers from the Centre to the states—became a core mechanism of nation-building. Kapur showed the audience a graph and explained how over time, transfers to the poorer states gradually increased.

“We all sort of get obsessed with the center and state relationship,” he said, adding that this has been an issue for decades. He pointed to a graph, again highlighting India as an outlier compared to China and USA. “In these countries, government employees are largely at the local or central level. In India, it’s the opposite—most government employees are at the state level.”

Also read: At elite Doon summit, old boys grapple with ‘egalitarianism’ and ‘aristocracy of service’

The state as a protector

Before walking the audience through the themes of the book, Subramanian jokingly noted the absence of the panelists, Ahluwalia and Doshi, hoping that they would apparate soon, a reference to a form of magical teleportation popularised in the Harry Potter novels. Both joined the authors for the panel discussion later.

“We don’t have just one theme,” said Subramanian, explaining that over 75 years, a diverse, complex India has had multiple political parties across 28 states. “But there is a theme of ‘precociousness’—democracy before development, services before manufacturing—that figures throughout the book.”

He went on to elaborate how India’s focus on high-skill activities and manufacturing services, over labour-intensive or low-skilled sectors, manifested domestically as “growth without structural transformation.” Between 1950 and 1990, the answer was self-evident—poor planning, excessive licensing, and stymied economic activity

“But the puzzle is, why in the era of rapid economic growth between 1980 and 2016 did India not have any structural transformation,” he said, rhetorically asking why the nation didn’t provide enough employment to an organised sector and reasonably high-paying, productive wages to large parts of the population.

He teased the audience by withholding the answer, nudging them to discover it for themselves through the book. But it was another theme that had the audience giggling—what Subramanian termed “Maaai–Baapism,” the ideology that views the state as a refuge and protector.

“The state may fail you consistently, but you will still turn to the state for providing what it is demonstrably incapable of providing,” said Subramanian, adding that one of the manifestations of this is a ‘lack of exit’.

He flicked to the next slide, which showed the returns on capital for central public sector undertakings. Poorly performing public enterprises rarely shut down, Subramanian noted, because of this reverence for the state.

“It’s been consistently low,” he said, referring to the returns on the chart that were below a red line denoting the benchmark rate. “And this is for central public sector enterprises. For state enterprises, it’s much worse.”

Also read: Dynasty politics, not patriarchal society, is Haryana’s real challenge: Abhimanyu Singh Sindhu

West Bengal puzzle

The panel discussion moved away from data points and charts, focusing instead on broader strokes to compare India’s growth—both internationally, with countries like China, and domestically, between its own states.

“What did China get right in those fundamental first 10-20 years,” asked Doshi, turning to the authors for their insights. “We seem to think a divergence between the two countries happened with Deng Xiaoping’s reforms in the late 70s. But you make the point that it happened a decade earlier, at a time when China was in deep chaos.”

“If you look at [agricultural] yields, the gap between India and China had already emerged significantly,” said Kapur, adding that for large agrarian societies targeting structural transformation, an increase in productivity in agriculture is crucial. “The second is an emphasis on building public health and primary education.”

Subramanian then touched upon three patterns of failures across states that they noticed. The first was the low-income trap of the Hindi heartland, which he said had been ‘studied to death in development’. The second was the meteoric rise and fall of Punjab. And the third was what went wrong in West Bengal.

“Bengal had unusual political stability since 1977—it just had three chief ministers,” said Kapur, adding that the state had several factors working in its favor, including its coastal location. “And the Left Front was unusual in its leadership—it was probably the least corrupt of any political party at that time.”

At the time of Independence, West Bengal was more developed than East Bengal (now Bangladesh), but today Bangladesh’s garment exports far exceed West Bengal’s. And over time, the state saw an exit of its financial capital and then human capital. Doshi asked the panel about the reason for this decline, this fall from grace for West Bengal.

“That is the puzzle,” said Kapur. “Bengal is the one state that was failed most by the intellectuals. They were far more aware of protesting about Vietnam and Cuba, but they [were] unwilling to look at what was happening in their own state.”

(Edited by Theres Sudeep)