Once a symbol of withdrawal and sacrifice, the Indian sadhu now appears across television screens, social media feeds, election rallies, and even corporate spaces. From spiritual gurus wielding institutional power to politically influential monks, the ascetic continues to shape public imagination.

The sadhu, or the ascetic, is one of the most popular postcard image of India, and of an enduring, deep and old civilisation. And yet, the Indian ascetic is a mystery for artists, philosophers, writers and scholars. And this knowledge gap in representation is what a new DAG exhibition in Delhi called The Body of the Ascetic tries to fill. Curated by Gayatri Sinha, the show will run until October 18, 2025.

“From Ajanta’s monks to Jain sadhus and Shiva as the maha yogi, the ascetic is a recurring figure in Indian art. Yet unlike gods or royals, he remains under-studied and enigmatic. DAG’s rich collection allowed us to cull images of the ascetic and see how he is imaged, through the decorative arts, the patronage of the royal courts, the colonial period and in the hands of the modern artist,” said Gayatri Sinha, the curator of the exhibition.

The exhibition explores spiritual, cultural, and artistic expressions across the Indian subcontinent—from early Sramana traditions to contemporary perspectives. It reveals how the ascetic figure has been revered, challenged, and reinterpreted across centuries, media, as well as religions.

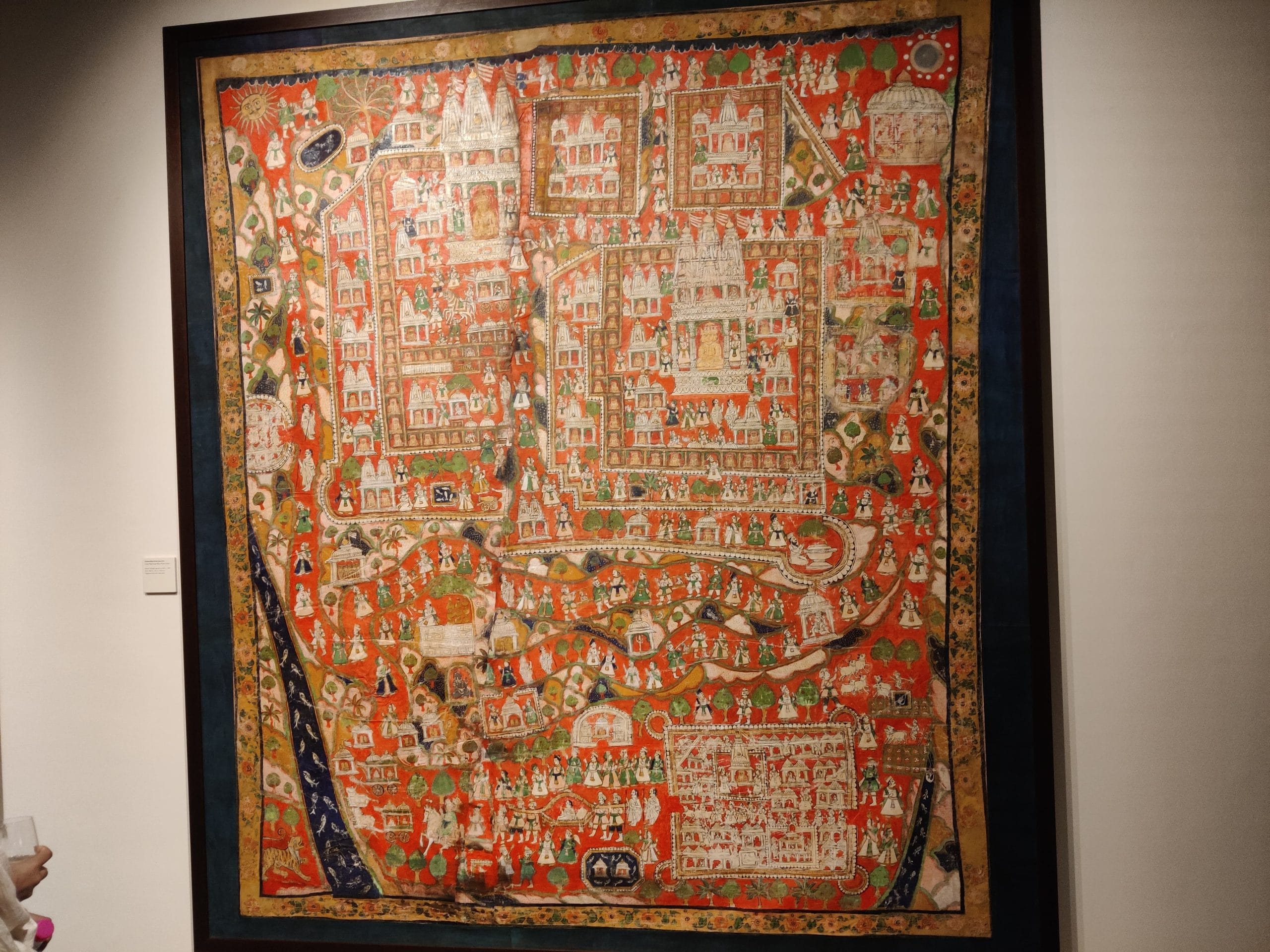

Far from a relic, the Indian ascetic remains a dynamic, evolving presence, transcending time, beliefs, and politics. Through sculptures, paintings, sacred maps, and modern art, the exhibition reflects on the spiritual and physical, the personal and collective, the revered and contested within India’s renunciation traditions.

Bengal’s diverse imagination

Four miniature paintings by Bireswar Sen open a meditative window into the Himalayan highlands. Against vast, mist-laden peaks and endless blue skies, a solitary figure is present, as if having transcended worldly struggles. Rather than fleeing life, the sannyasi appears to have arrived — to have sought refuge not from the world, but within it.

“Sen spent long periods in the Himalayas and developed a highly refined miniature style. Landscape was never a forte among Indian painters, but in Sen, grand vistas are presented in very small format, with great success,” Sinha said, adding that appreciation for his work returned with BN Goswamy’s exhibition—Heaven and Earth: Himalayas and the Art of Bireswar Sen.

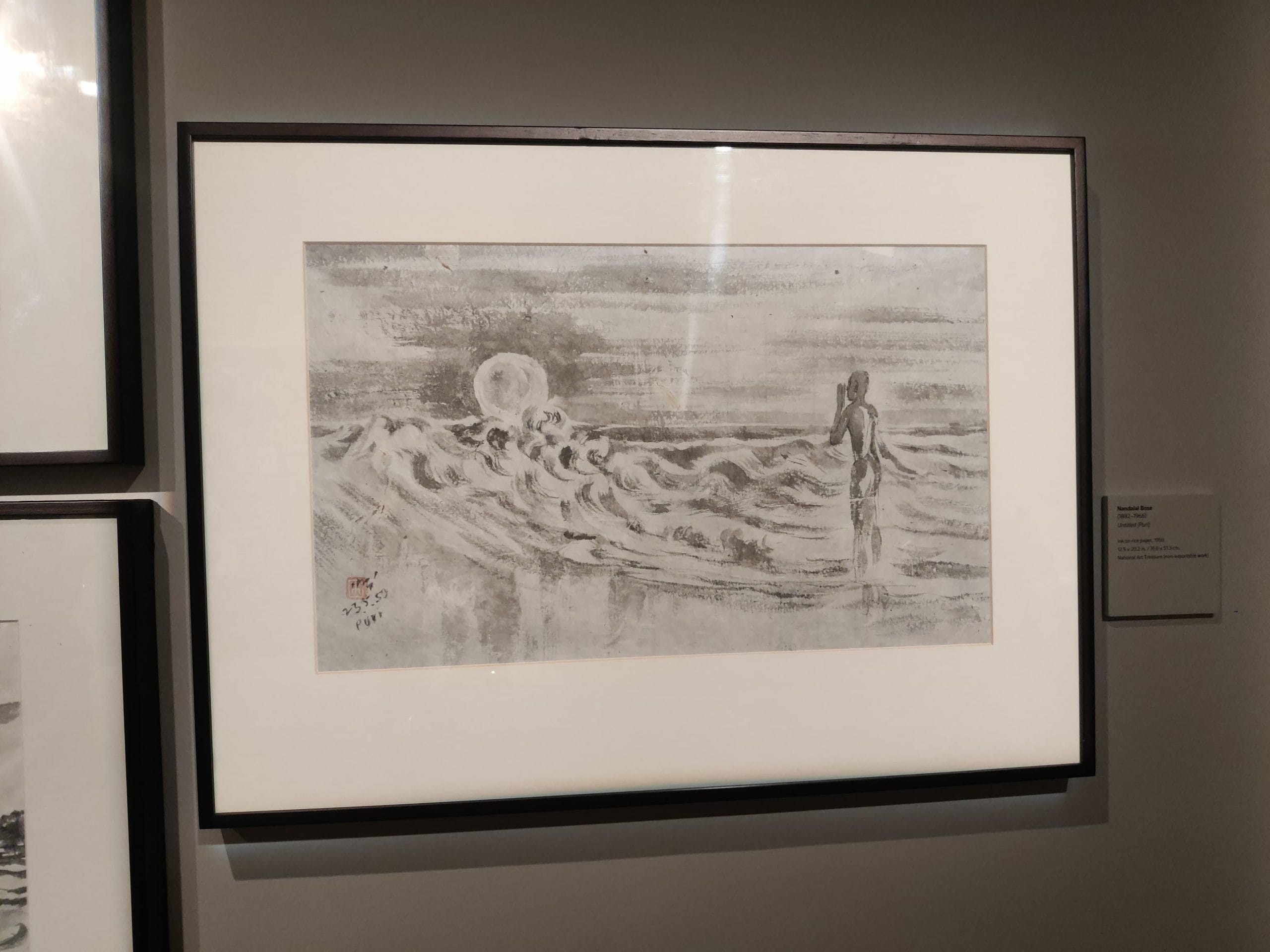

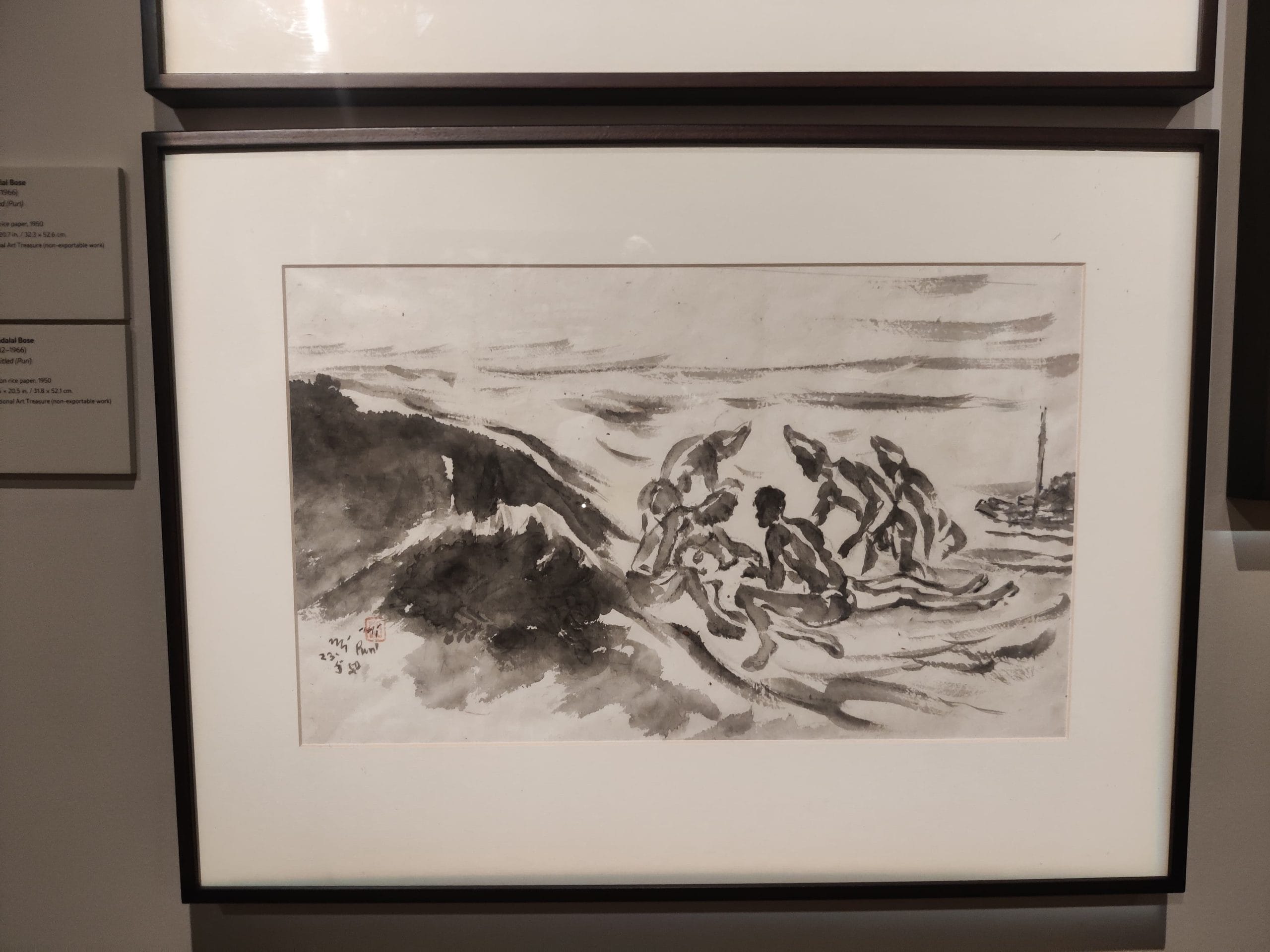

From the mountains to the coastal waters, Nandalal Bose’s three monochrome watercolours portray a similar introspection. Known for his masterful line work in pen and ink, including illustrations for the Constitution of India, Bose employs a looser brush, capturing solitary figures at the edge of the sea, possibly along the Puri coastline.

“It is documented that he visited Puri during the death of his father,” Sinha said. “We gain a sense of a man meditating on the edge of the waters. Another interpretation is that it references Sri Chaitanya’s ritual entry into the sea in Puri, whereafter he was not seen. To transcend the personal with such minimal means is what makes these works exceptional.”

This meditative visual language is deeply rooted in Bengal’s spiritual and literary traditions. From the Vaishnava Bhakti of Chaitanya Mahaprabhu to the reformist fervour of the Brahmo and Prarthana Samaj movements, Bengal fostered diverse models of renunciation.

These influenced not only religious life but also the arts and literature—most notably in figures like Bankimchandra Chattopadhyay’s Anandamath and Sarat Chandra Chattopadhyay’s Srikanta, which recast the sannyasi in a modern, empathetic light.

This more humane vision found form in the work of Santiniketan and Calcutta artists—Nandalal Bose, Asit Kumar Haldar, and Kshitindranath Majumdar—who explored the ascetic body not as exotic or marginal, but as a figure of quiet strength.

Also read: This 15-minute film on Down Syndrome took 21 years to make. The audience was in tears

Asceticism in transition

British authorities often viewed ascetics with suspicion and hostility, perceiving them as lawless rebels. The militant Sannyasi Rebellion of the late 18th century was an example. Armed monastic orders fought British forces, symbolising spiritual defiance and nationalist resistance.

Colonial administrators like William Sleeman demonised sadhus as “robbers in disguise,” while Indian nationalist literature, notably Bankimchandra Chattopadhyay’s Anandamath, celebrated the sadhu as a patriotic freedom fighter, fusing spirituality with political activism.

At the cusp of modernity, figures like Swami Vivekananda projected the ascetic onto the global stage, blending aristocratic dignity with spiritual wisdom at the 1893 Chicago Parliament of Religions, crystallising the image of the Indian yogi worldwide.

And when it comes to post-independence India, the figure of the ascetic has not faded; it has multiplied, adapted, and taken on new, sometimes contradictory roles.

“The exhibition seeks to demonstrate that the ascetic, even if he belonged to a sangha, finally operates as an individual,” said Sinha. “He is a non-state player, a figure on the margins who has historically been close to dramatic changes in Indian history.”

Through colonial times, she added, images of sadhus, often focused on extreme austerities, became a visual obsession, distracting from the spiritual intent of their practices. “Innumerable photographs, prints and watercolours sought to depict the sadhu, his extreme forms of bodily mortification, and his way of life. All of this drew attention away from what the sadhu represented, or the authenticity of his quest.”

Contemporary artists build on this legacy, but often with a more critical lens. Some works question the romantic ideal of the renunciate by confronting contradictions. In one Kalighat Pat, An Ascetic Suckling at a Woman’s Breast, the satire is sharp, unmasking hypocrisy behind religious postures. “Traditionally and historically, they have exploited their positions of power in certain ways. That becomes the more contemporary angle,” the docent said.

Legal ambiguity adds another layer. By law, a sannyasi is considered to have undergone “civil death,” renouncing property and inheritance. Yet in reality, many spiritual leaders command empires, triggering legal disputes and institutional strife. At the same time, popular culture continues to glorify the ascetic body, from Raja Ravi Varma’s mythic paintings to modern media’s fascination with mystics and yoga gurus.

Today’s ascetic is no longer just a recluse in saffron robes but a shape-shifting figure–sacred and political, admired and critiqued, traditional yet constantly reinventing itself.

(Edited by Saptak Datta)