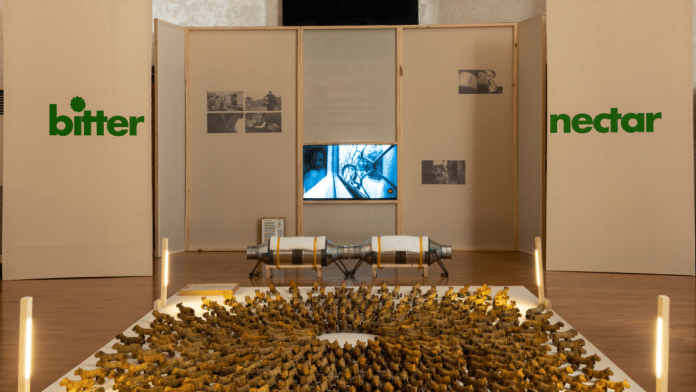

New Delhi: A battalion of more than 500 tiny, clay lions in perfect concentric circles greet viewers as they enter the Sustaina India exhibit at Delhi’s Bikaner House. Their arresting presence alludes to a larger ecological problem — single-species conservation in the Gir forests — and how Asiatic lions in Gujarat are now moving beyond their original habitat, in search of wider territory.

The exhibit featured a display titled “Mari Vaadi Ma”, which translates to “in my farm” in Gujarati, by artist Mrugen Rathod. The lion figurines also have a second layer of meaning, which their yellowish-orange hue alludes to. As Gir’s lions spread out of the national park, they are increasingly entering the mango orchards that populate farmlands nearby.

This standoff between single-species conservation and single-cash-crop cultivation is what Rathod wanted to portray in his piece for the third edition of Sustaina, a collaborative art exhibition organised by the Council on Energy, Environment and Water (CEEW) and curated by artists Jiten Thukral and Sumir Tagra.

“For most of us, art is our lived reality. If we can find a way to portray climate change and sustainability through it, all the better for us. It is a great way for inviting people to engage with our work and research in an interactive manner,” Arunabha Ghosh, CEO of CEEW, told ThePrint.

The theme for this edition is “Bitter Nectar”, and the ten art installations in the 15-day exhibition that ends on 15 February all feature a complex interplay of food systems, labour, climate change, and ecology.

The place was packed full on 31 January evening, as the third edition of Sustaina had its preview showing. Beyond the artists and CEEW stakeholders, the event was also attended by college students and policy practitioners, who wanted to see how the policy plays out in real life.

“We try to use numbers and figures and policy drafts to convey the problems of climate change in food systems, but this shows me that it is actually art that truly convinces you,” said Purnima Menon, an analyst at the International Food Policy Research Institute, to ThePrint.

Apart from Rathod, the exhibition is also featured Vedant Patil and Anuja Dasgupta among the seven invited artists whose work covered a breadth of subjects from Kochi city’s multiple climate stresses, to the lost art of sign painting, to even air pollution norms and labour erasure in New Delhi. Each work of art was accompanied by detailed write-ups giving clues to the deep research and context behind the artwork, seamlessly integrating the work of Thukral and Tagra with CEEW.

“Bitter Nectar is an exhibition that traces the politics embedded in the pursuit of sweetness and perfect ripeness, through works by artists who gently peel back the layers connecting fruit, climate, ecology,” read the Sustaina brochure.

Also Read: The Global Big Cat Summit is the only win for conservation in Budget 2026

The artists

Rathod was one of three artists selected for the Sustaina Fellowship to display his artwork that best portrayed climate change and resilience in Indian societies.

While his art centred around the Gir forests in Gujarat, where he spends his time researching, his fellow artists chose places like Ladakh and even Delhi-NCR as their focal point, building narratives about food and climate change from the most innocuous-seeming artefacts.

A milk train that Patil used to take in the Delhi NCR region inspired him to explore the nature of labour, transport and sustainability around milk production and delivery in India’s capital city through a film. Whereas, Dasgupta’s work with orchards and farming communities in Ladakh led her to create an intricate, interactive wooden puzzle using repurposed poplar wood, tracing the story of apricot production in the region.

Artist Sidhant Kumar,explored the dual crises of labour and air pollution in Delhi through the green fabric used to cover construction sites. This cloth, mandatory as part of the Graded Response Action Plan (GRAP) during heavy air pollution days in the city, was used by Kumar to make human figures, as a metaphor for the invisibilisation of labour in Delhi’s smog. While the cloth conceals the construction labourers from public view, the people engaged in the labour themselves are not protected from the dust and pollution of their work.

“Each of the fellows are deeply rooted in the communities and ecosystems they are representing in their art,” explained Manasvita Maddi, the curatorial assistant of the exhibit. “There’s a lot of ethnographic research that has gone into their art.”

(Edited by Insha Jalil Waziri)