New Delhi: The roses, transformed into the sweet balm of gulkand, paired with basi roti, offered small comforts to those on long, arduous treks through the valley.

Their scent would drift far from the fields of Choa Saidan Shah in Pakistan’s Punjab, offering weary pilgrims a fragrant promise of solace as they journeyed to the sacred shrine of Katas Raj. Today, those roses bloom again in artist Seema Kohli’s painting Gulab Ke Khet, part of her exhibition, Khula Aasman, at the Partition Museum in Ambedkar University.

She has recreated the world her father left behind during Partition. A home she may never see, yet one she has rebuilt with memory, loss, and inherited stories.

In the painting, a caravan of camels symbolises the pilgrimage to Katas Raj, set against the distant backdrop of the salt range. Overhead, the sky is overlaid with a map of Greater Punjab, marking both a place and a longing that transcends borders.

“Migration is natural for all living beings—birds, animals, and humans. But forced migration, eviction for political reasons, is a wound that should never repeat. My work serves as a reminder of that history, so we never forget it,” the artist said.

The exhibition, Khula Aasman, is a visceral journey through the fault lines of memory and migration, tied to the cataclysmic rupture of Partition. Inspired by her father KD Kohli’s autobiography Mitr Pyare Nu, she reconstructs her ancestral home in Pakistan’s Pind Dadan Khan, where eighteen generations of the Kohli family lived.

Through mixed-media works, silver gelatin prints, and a recreated Dava Khana (Unani pharmacy) steeped in her family’s healing traditions, the exhibition shows the human spirit’s capacity to preserve, adapt, and find beauty even in the aftermath of profound upheaval. Avian motifs throughout the exhibition, symbolising defiance of gravity and man-made borders.

“This book (Mitr Pyare Nu) is the document of the time of the changing eddies of sociological, political, logical and critical currents, which in a sense made up the people we are, the nation we became,” said Sunil Mehra, a journalist, filmmaker, writer, and Dastango, in a book reading session.

A healing legacy

After the death of KD Kohli’s wife in 1998, he completely immersed himself in his work, trying to fill the void in his life. He always wanted to write a book, and with Seema Kohli’s encouragement, finally began reliving his days in Pind Dadan Khan, a town nestled by the salt range between the Jhelum and Indus rivers.

“What do you think? I don’t have time. I have much more limited time than you,” he’d say whenever she arrived late to meet him.

Mitr Pyare Nu is a vivid portrait of life in Pind Dadan Khan, its land, people, birds, and everyday life, exploring the changes brought by Partition.

These stories became the seeds of Seema Kohli’s exhibition, a bridge between her father’s memories and her own artistic interpretations. Among the most enduring symbols in her work are roses—resilient, enduring, and deeply evocative of hope and healing.

For Kohli’s great-grandfather, Hakeem Chunni Lal Kohli, an eighteenth-generation Unani practitioner, roses were the source of gulkand (rose petal jam), a cherished medicinal preserve celebrated for its healing properties.

“Gulkand was a very common sort of remedy for all kinds of weakness. It was sort of a cure-all within the Kohli family household and was very prevalent within Hikmat (another name for the Unani system of medicine),” said Adwait, the curator of the exhibition.

A central feature of the exhibition, the Dava Khana reflects the family’s centuries-old Unani medical legacy. Hakeem Chunni Lal Kohli was renowned for his holistic approach to healing, blending scientific knowledge with a deep understanding of nutrition and sensory memory.

The Dava Khana is a sensory experience that invites visitors to touch, smell, and even taste elements of this rich legacy. Recipes for gulkand and murabba, derived from Hakeem Chunni Lal’s Urdu medical texts, have been brought to life. The space is suffused with the aroma of herbs, recalling a time when healing was an intimate part of daily life.

“Smells often carry the weight of memory. Through these archives, we’ve tried to resurrect the forgotten language of medicine,” said Ishita Dey, an anthropologist, who collaborated with Kohli on the Dava Khana section of the exhibition.

Dey highlighted the role of Urdu in medical education, a detail brought to life through the preserved texts of Hakeem Chunni Lal Kohli, whose work served both the people of Pind Dadan Khan and post-Partition India.

“Urdu is not the first language that comes to mind when we think of medical training. But these texts reflect a wealth of knowledge about botany, anatomy, machines, and modern medicine. The main text is in Urdu, while the appendix is in English, showcasing an engagement across languages,” she said.

Also read: India’s pathshalas were inclusive institutions. Dalits, Brahmins studied together

A reminder

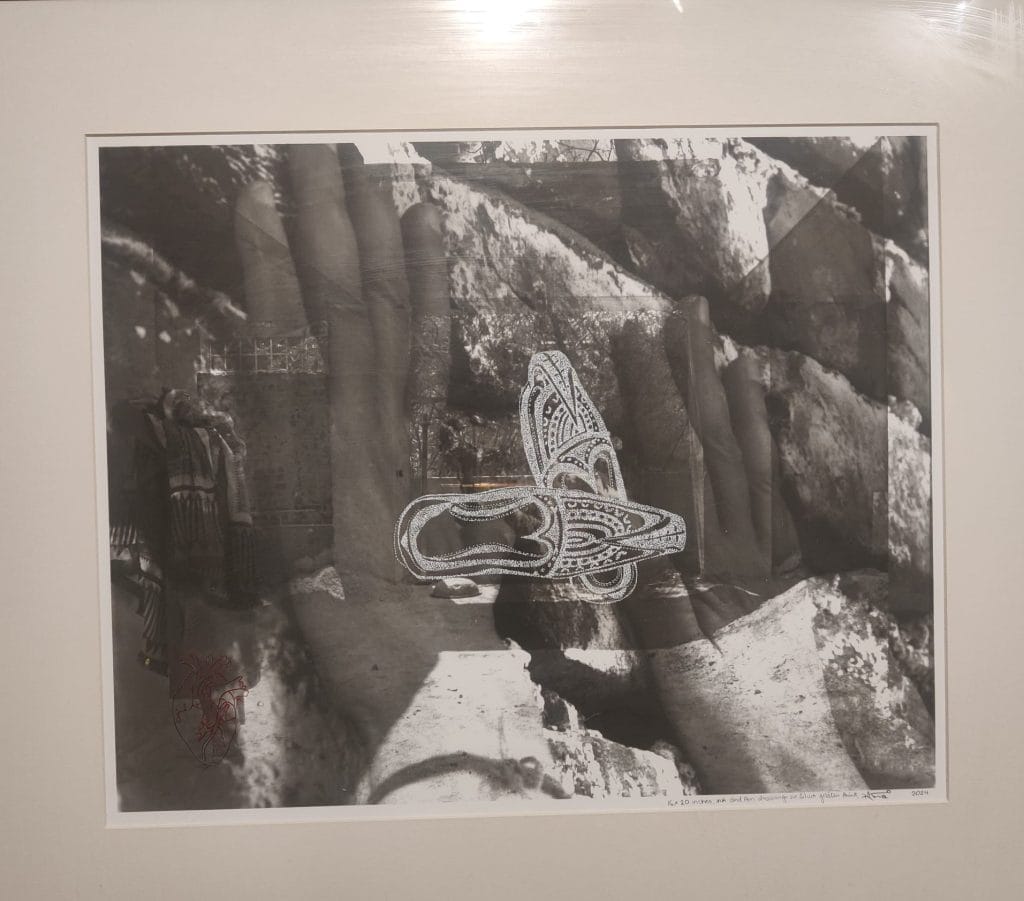

The exhibition also features silver gelatin prints recreated from photographs taken by Kohli’s father with his Fuji camera, gifted by his elder brother in 1937. The photographs, brought safely to India during the family’s migration, are now reimagined using the same Fujicolor paints her father once used.

One silver gelatin print captures the essence of an afternoon in Pind Dadan Khan, described by Kohli’s father in his book. Overlaying the image of hands is a pair of juti (footwear), made by the same Fujicolor paints. As the Muharram procession passed by in the street lane, a little girl dropped her juti from the balcony right in front of the Tazia (a miniature replica of the tomb of Imam Hussain).

The sudden silence that followed was palpable. The procession leader, understanding the accident, calmly pushed the juti aside with his foot, and the procession continued without a hitch.

“It was an act of understanding, a moment of compassion that seems rare in today’s world, where such an incident would likely have sparked anger or conflict,” Dey said.

Another work depicts the train at Pind Dadan Khan station, a haunting symbol of Partition. Once a lively place where Kohli’s father played as a child, it became a site of tragedy, with trains carrying lifeless bodies from both sides of the border.

“My father said it once brimmed with laughter, but after Partition, suddenly the place was only reminiscent of massacres and blood,” Kohli said.

Kohli’s work transcends loss, honoring the resilience of the human spirit. While she moves forward, she refuses to forget that time, serving as a reminder of what must never happen again.

“I’m moving on from there, to the Khula Aasman, to the possibilities these people carried with them. There was sorrow, nostalgia, and pain. But their focus wasn’t on the past, it was on building new lives, a new nation,” said Kohli.

(Edited by Aamaan Alam Khan)

Seema Kohli seems to be pining for Pakistan. Why not give her Pakistani citizenship and allow her to settle down in Pakistan?

Also, The Print might be able to help. It has expertise in the domain of “Go To Pakistan”.