New Delhi: The Gateway to Hell, the River of Sorrow, the Headache Mountains, and the Stream of Silence — these were only some of the treacherous routes traversed by the intrepid explorer, Rasool Galwan.

The explorer who died in 1925 had guided European expeditions safely across the Himalayas, and it’s his name that adorns the Galwan Valley today.

Galwan’s incredible life was the subject of an illustrated lecture by Brigadier Ashok Abbey on 17 January at the India International Center, with Ahtushi Deshpande as moderator, former Ambassador Shyam Saran as the chair, and historian Janet Rizvi as distinguished speaker. The audience included Galwan’s great-grandson, Amin Galwan.

At the turn of the 20th century, Leh and Ladakh became the forward bases for explorers, traders and scientists to meet. For centuries, it had been a hub of trade — luxury goods and narcotics would pass through the region on the Silk Route. And even though these were not consumed in Ladakh, they created a huge demand for caravans, men, and horses.

This is how Galwan got his start, as a young pony-boy on a European expedition. Over time, he became the best guide and explorer, highly sought after for his expertise and knowledge of the region.

Abbey’s illustrated lecture gave the audience — of which over half had already been to Ladakh — a glimpse into the region’s terrains, and the risky routes Galwan had to take. His expertise and experience impressed the British so much that they named the valley after him.

“The name of Rasool Galwan will always be etched in the history of Ladakh in golden letters. Not just because a historical feature is named after him, but because of the man he was — a gentleman in every situation,” said Abbey at the end of his lecture.

“I have no doubt that as long as the mountains of Ladakh stand tall, the passes high and the valleys pristine, the legend of Galwan will always reverberate and inspire intrepid explorers.”

Also read: Mir Taqi Mir sidelined for too long. His manuscripts being archived now

A cosmopolitan context

In the late 19th century, Leh was a cosmopolitan melting pot tucked high into the mountains. Merchants would swarm in “picturesque confusion,” carrying saffron from Kashmir, leather from Russia, carpets from Bukhara, and wares from Balochistan. There were Indian fakirs, Muslim dervishes, and Buddhist singers — all contributed to the hustle and bustle of Leh.

“Surely that was a stimulating atmosphere for a bright boy with big dreams!” said Rizvi, referring to the context in which Galwan grew up. It proved to be the perfect base for European expeditions — and the perfect training ground for Galwan.

He grew up fascinated by the caravans that passed through Leh, and the people it transported. An exceptional child, Galwan was raised by his mother and was so curious about the world that he asked the headmaster of the local school if he could enroll for free. He was too poor to pay its fees. He learned to read and began to speak five languages, but didn’t learn to write very well.

He was enamoured by the foreign merchants he saw at the “great meeting ground” of Leh, and would listen to stories about their travels.

Eventually, Galwan began to accompany famous explorers like Francis Younghusband, Lord Dunmore, and Church and Phelps. He learned to carry all kinds of tools to aid him during the long journeys — abacus for counting, measures and scales and medical equipment.

“With his combination of qualities, he might well have been the right man almost anywhere, at any time,” said Rizvi.

Great dangers

Abbey’s lecture offered AI-generated images alongside real photographs to estimate how busy Leh would have been, and what difficulties Galwan would have had to go through.

“Ladakh is a land of high mountains and desolate windswept areas — it’s a land where either the best of friends meet, or the worst of enemies,” said Abbey. “For centuries it was crisscrossed by armies, merchants, and traders because it’s located strategically at the crossroads of Asia.”

It was also of strategic importance, pointed out Saran, who had been there many times as both foreign secretary and while working at the Prime Minister’s Office to undertake border infrastructure surveys.

“Ladakh is known as the land of high passes. People often carried a shroud with them, so they could be buried with dignity if they died,” said Deshpande.

The nerve that Galwan displayed must have been incredible. Abbey talked about how what Galwan achieved at the time — with no modern tools or equipment — was “absolutely phenomenal”.

At one point, after the lecture was over, Rizvi and Abbey had a debate about the exact date of Galwan’s birth. He was rumoured to have been born in 1878, but history records his expedition with famous British explorer Francis Younghusband in 1890 — which means he would’ve made that dangerous journey at the age of 12.

Abbey quoted Galwan’s own words: “I was in a hurry to get old!”. He was known to have said.

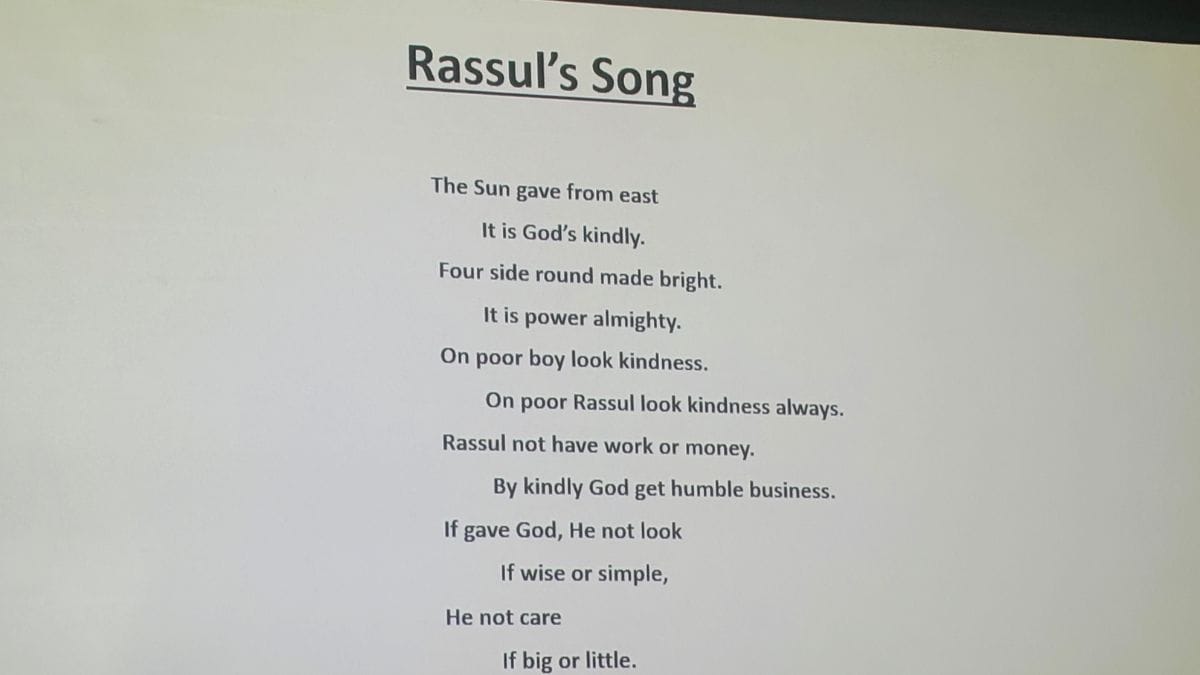

The lecture also included a poem called Rassul’s Song, written by Galwan in broken, simple English: “On poor boy look kindness/ On poor Rassul look kindness always/ Rassul not have work or money/ By kindly God get humble business.”

(Edited by Ratan Priya)