New Delhi: For the first time in India, Peter Nagy’s black-and-white silkscreens reveal the restless energy of 1980s New York. Personal and meticulously crafted, they reflect his experiences — from New York to Europe, from family loss to cultural observation.

These silkscreens are part of the exhibition America Invented Everything, currently on view at Nature Morte in New Delhi. It brings together a portfolio of silkscreens produced in Italy in 2022, reproducing works Nagy originally made between 1983 and 1991, during his years in New York.

Made for a Venice show curated by Richard Milazzo, the pieces include photocopy collages, enamel-on-metal signs, and acrylic paintings. They demonstrate how Nagy fused art history, popular culture, and advertising with graphic design strategies.

“The piece, America Invented Everything, was made in 1985 on my first trip to Europe. I had an objective viewpoint of America. And the hubris and the sort of egotistical — America thinks it’s so great. We’re the greatest country in the world. And then you go to Europe, and you’re like, wow, look at this. This is amazing. It’s so much nicer. So it’s totally sarcastic,” Nagy told ThePrint.

Timelines

Nagy’s early works draw directly from New York’s streets. He got his inspiration from posters, handbills, and fleeting images.

“I wanted to make artworks that functioned as pure information,” he said. “Some were photocopies sold for a few dollars, others laminated. They were made to be reproduced. The work had almost no material value, but carried a message about the time and place it was made.”

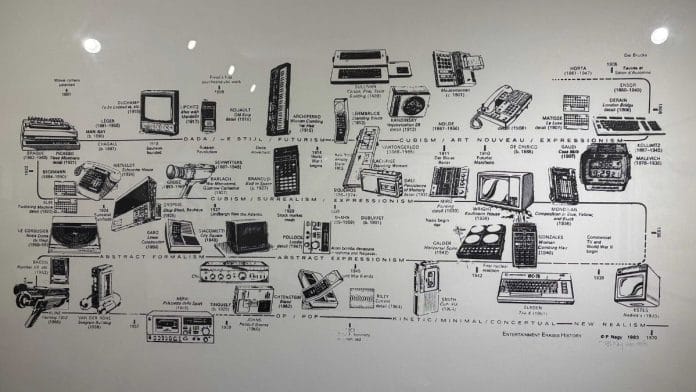

A common theme runs through these pieces: timelines. In The 8 Hour Day, the top eight art stars of 1983 become the numbers on a Rolex watch. In Entertainment Erases History, images from Nagy’s art history textbook are met with early media technology, anticipating how recording, playback, and later social media would overwrite reality.

For him, time is not linear; it is assembled and reorganised.

“These were the timelines in my art history books, and I was just slotting in different images, asking myself: how do we visualise art history? I studied art history, theory, and graphic design, but not traditional fine art or painting,” said Nagy.

Personal experiences shaped the works, too. In 1984, Nagy lost his father and grandmother to cancer. This led to the Cancer Logos and Cancer Paintings, where clip art, logos, and images were fused into abstract patterns.

“When family members die of cancer, you are drawn to reading about it,” he said. “I applied the logic of cancer to my work: it replicates and wipes out the healthy cells. People often thought I had blown up a cancer cell under a microscope, but it was all collaged, repurposed, and painted.”

Sign of Malignancy and America Invented Everything are examples of how the personal and the social coexist in the artist’s vision.

Also read: What is loyalty in a polyamorous relationship? Kerala Lit Fest looks for an answer

Ornament as a disease

Travel profoundly shaped Nagy’s artistic vision. A Million Dreams blends maps of Egypt, Paris, and Italy’s Lucca — three places that left a deep imprint on him.

“Lucca in Tuscany, Paris, and Egypt all shaped my perception,” Nagy said. “It was a mix of personal experience and the places I encountered. A Million Dreams is about those first travels, the cultural and architectural influences, and how they stayed with me.”

His architectural works, like L’Age d’Or and God Lie, explore Baroque, Rococo, and other historical styles. While travelling through Italy, France, and Germany, Nagy perceived Baroque and Rococo not merely as artistic styles, but almost like a type of cancer, spreading through cities, decorative arts, and architecture.

“I thought of ornament as a disease, and my work reflects that. Still collage-based, still built from multiple images, but now abstraction dominates,” he said.

India has also shaped his work. Arriving as a tourist in 1990, he stayed, inspired by the country’s culture, architecture, and art. The experience encouraged him to experiment with ceramics, colour, and three-dimensionality.

“I came to India for a year, not knowing anyone, and ended up staying for 35 years,” he said. “You never stop learning here. It changed how I approach materials, colour, and space. But the logic of how I play with images, cutting, combining, building, remains consistent.”

The exhibition will run until 14 February.

(Edited by Aamaan Alam Khan)