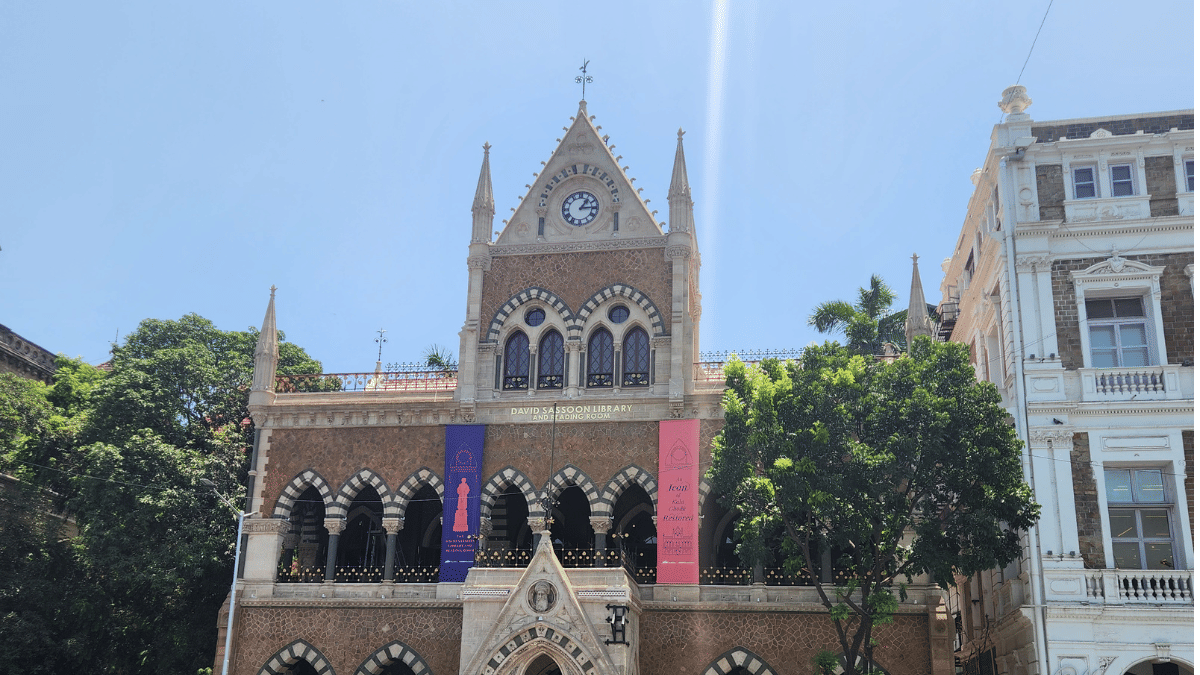

Mumbai: After 16 months and a budget of Rs 3.6 crore, the David Sassoon Library and Reading Hall in Kala Ghoda, Mumbai, has started a new chapter of its more than 150-year-old history — one that brings its glorious past to life. The two-storeyed Victorian neo-gothic-styled library has long provided a quiet space to civil services aspirants, students, and researchers. With an archive of around 30,000 books, magazines and newspapers, it has now been repaired, restored, and resuscitated.

The team comprised leading conservation architect Abha Narain Lambah, supported by the JSW Foundation, ICICI Foundation, Kala Ghoda Association, Consulate General of Israel, Mumbai and Tata Trusts, had many challenges to address.

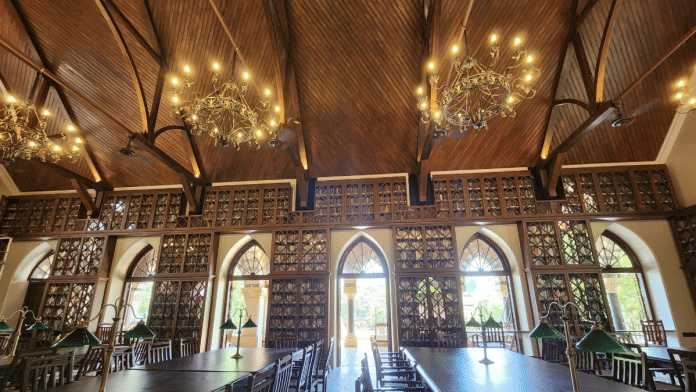

They battled termites, tackled a leaky roof that had wreaked havoc on thousands of old books, repaired the original teak tables, and worked on the arches and stone facade of the building. And the result is a labour of love that embraces everything from the antique switches to the chandeliers—the reading room alone has five. A large portion of the original richly patterned Minton tile flooring was also restored.

Also read: Jamini Roy family says ‘prayers answered’. His house-museum a window to modern Bengali art

Long overdue renovation

A complete restoration of the David Sasson Library had long been overdue.

“The structure was getting repaired time and again. So we decided to go for a permanent restoration,” says Hemant Bhalekar, president of the library.

The heritage building once housed around 70,000 books in five languages, including Kannada. But around 40,000 books, maps, periodicals, and other priceless documents were destroyed over the years due to repairs, leakages, and poor maintenance.

Today, the library’s archive is filled with English, Marathi, Hindi and Gujarati books. The management hopes to maintain its entire collection now.

The project was initially scheduled for 2020 but was delayed due to the Covid-19 pandemic. A Grade I UNESCO heritage site, the David Sassoon Library finally opened its doors to visitors on 3 June. For now, though, the reading room is still empty of patrons. The library will be open to members and visitors in a couple of weeks after the final work on the side overlooking the garden is completed.

Also read: Delhi’s Partition Museum remembers pain of separation—through artefacts, images, personal items

Piecing the history

Lambah and her team dove into the restoration work like detectives, piecing together the library’s past and tracing its architectural evolution that came about with repair work through the years. They stumbled upon an old photograph that showed the reading room with a sloping roof, which had been flattened in the 1960s. Now, it has been restored to the original.

“The major challenge was the fact that the original roof had been replaced with a concrete slab in the 1960s. This concrete slab had deteriorated and needed to be structurally replaced,” says Lambah.

An exciting discovery was an old gas pipe on the ground floor. It suggested that the entryway had been gaslit. The pipe has been restored and occupies its original position, though the building is no longer powered by gas.

“Wiring, lighting, and other interiors also were challenging,” adds Lambah. More inspiration came from old watercolour drawings of the building.

According to Lambah, the library could only afford Rs 28 lakh, which is just a fraction of what the task entailed. “So I approached Sangita Jindal (chairperson of the JSW Foundation) as she had been supporting a lot of such conservation projects,” she says.

A circular staircase from the reading hall leads to the upper deck, which has balconies on both sides. The fascinating structure, though, isn’t open to the public. Bhalekar says that the balcony railing isn’t too high, and they don’t want anyone falling over.

From the upper deck, the restored staircase leads to the tower clock, which is manually wound twice a day.

Baghdad to Bombay

The David Sassoon Library building was one of the first to come up in the area after Fort George was demolished in the 1860s. The land was auctioned off for development, and David Sassoon, a Jewish banker and merchant bought one piece of the land. Incidentally, his son changed his name from Abdullah to Albert, moved to England, became a Baronet and married into the Rothschild family, the infamous European banking dynasty.

Sassoon, born in 1792 to a wealthy merchant family, had fled to Bombay in the 1830s after facing persecution in Baghdad. In 1853, he was granted British citizenship in recognition of his services to the Empire.

On that piece of land, he set up the Bombay Mechanics Institute, built on a budget of Rs 1,25,000, of which more than half was given by Sassoon, according to Bhalekar. It was renamed Sassoon Mechanics Institute, and later, in 1938, the David Sassoon Library and Reading Room.

Most visitors are familiar with the reading room and its balcony that overlooks the busy Kala Ghoda square. Its floor-to-ceiling bookshelves, arches, long tables, chairs, and bankers’ lamps evoke the nostalgia of grand libraries.

It’s frequented by Maharashtra Public Service Commission (MPSC) and Union Public Service Commission (UPSC) aspirants, lawyers from neighbouring courts, and old residents of South Mumbai.

The David Sassoon Library has over 2,000 members currently, and the management hopes the number will increase now. Annual and life membership fees range between Rs 5,000 and Rs 25,000. And it costs you peanuts to use the reading room — anyone can use it for Rs 10 for a day. Here, with dappled light from the arched windows, time stands still—the ghost of a Bombay that is long gone.

But it is not stuck in time.

The David Sassoon Library and Reading Room now has WiFi, and patrons can use smartphones, e-books, and tablets.

“We have to look forward as well,” says Bhalekar.

(Edited by Humra Laeeq)