Jaipur: Poet and lyricist Javed Akhtar’s mother continues to influence his writing, he said at the Jaipur Literature Festival on Thursday. His mother died when he was just eight years old.

“My mother is probably where I got my first interest in language from. She used to play these games with me where she would tell me ‘Okay, this is a word, what all can we do with it?’”, he said.

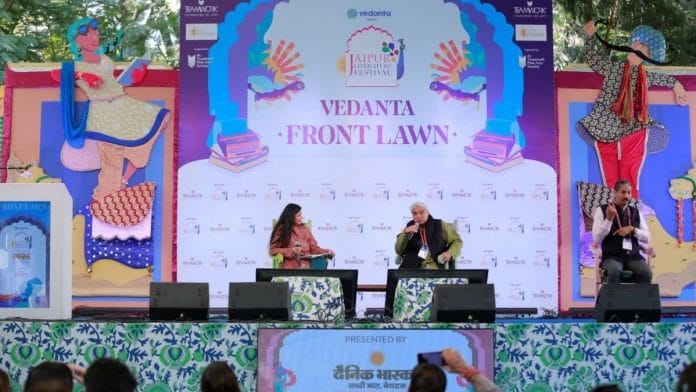

Akhtar was in his element as his first session at the JLF 2026 took place at the Vedanta Front Lawn. A large crowd of fans, fellow writers, and media members from different age groups thronged to witness the genius. His session titled ‘Javed Akhtar: Points of View’ in conversation with Warisha Farasat chronicled the poet’s journey from his first literary influence to the ever-changing landscape of the Hindi film industry.

Farasat, a lawyer by training, opened the session by asking Akhtar about his mother, Safia Akhtar, and the influence she had on his literary life. Akhtar quipped that at this point in his life, he should be talking about his granddaughters instead.

He added that his mother was a voracious reader and would often tell him the stories of the books she read, of course, “editing out the romantic parts”.

“Even now, when I’m writing a poem or a script, I think and remember the books that my mother read to me as a kid. It still inspires me.”

The secularism coefficient

The conversation moved on to his literary influences and growing up surrounded by his fellow poets and family members, his father Jan Nisar Akhtar and his uncle, Majaz, along with members of the Progressive Writers movement. “One cannot decide to be influenced by someone; it seeps into you. Influence goes inside you without any consciousness.”

Akhtar gave the example of secularism. “There is no crash course in secularism; it should be a way of life. If you have to be taught that, then it’s fake, artificial, but if you are raised with it, then it becomes a part of you,” he said.

The Sholay (1975) writer gave the example of his maternal grandparents. He said his Nani, who was illiterate, didn’t allow his Nana to impart any religious teachings on the young Akhtar, arguing that his mother and father weren’t religious, “She said, and I remember it clearly, ‘Who are we to impose religion on him.’ A lesson that many politicians can learn today. I wish leaders today had even one-tenth of that sensibility.”

In his usual quick-witted manner, Akhtar, when asked to recite a poem, responded with: “Why. Do you not have any more questions?” He added that it’s taking him a while to think of one because he only writes two kinds of poetry: long and very long.

Bollywood and the changing world

Farasat also mentioned the concept of the “angry young man” that he, along with Salim Khan, had created for Bollywood. She asked how it fits into the current landscape of the film industry.

“Cinema is not a void; it is an integral part of society. It can only manifest what is happening in society. It changes with time. There was a time when Devdas was a hero — a cult figure. There was the rebel star, who would only rebel against his mother, usually Lailta Pawar, to marry the woman he loved,” Akhtar said. “There was also a time when rich producers would make films to preach socialism because there was money in it. Then there was the vigilante, who coincided with the Emergency. It shows the changing morals and aspirations of society, so with it, the hero also changes.”

The poet added that the Indian film industry is far more democratic now than when he started out.

“The golden era is never the present era. Even Aristotle was unhappy with the younger generation of his time. Life offers you packages with both good and bad. We view time past as always being better, but I think the film industry is much more organised now than it was when I was starting out. It is much more democratic as well,” he said.

“When I was an assistant director, our job was bringing Madam her shoes or ‘Arrey, hero sir ka coat rah gaya, jaldi le kar aao (Oh, the hero forgot his coat, fetch it quickly)’. But I see ADs now, and they are on a first-name basis with the actors. I get scared just looking at them.”

He went on to say that people nowadays often critique the current songs, but the blame lies within themselves. “Ask any young person today if there is a poetry book in their home. If they have read any poet, if their parents have. When they were younger, did they spend any time with any poets? You have broken the child’s relationship with language and are now blaming the poets,” he exclaimed to uproarious applause.

Also read: Jaipur Literature Festival opens with a literary red carpet—Shalini Passi, Stephen Fry

Faith, death & cockroach

Budding writers and poets were keen to know the legendary writer’s opinions and suggestions. When asked what advice he would give to younger writers, Akhtar said: “Read. Intake is a must before output. Before whatever and whoever you choose to write for, read. Read indiscriminately.”

He also remarked that there must be some “latent violence” among all of us, which is why there are so many violent and action-packed movies nowadays.

In typical fashion, Akhtar kept the conversation flowing freely, even going so far as to demand that the remaining 10 minutes be extended to 20. He joked with the crowd and, after a few women-only questioners, wondered if men were banned from asking questions.

A young man asked that every revolutionary comes with a threat to life, so how can an atheist motivate himself when he knows that life ends with death? “Everyone believes that death is the end, and only a few believe that there is a life after death. If there is a life after death, then die! If there is a heaven waiting for you, then how foolish is it that you are alive,” Akhtar replied.

He then wondered whether a cockroach, if killed, also goes to heaven or hell—or if that fate is reserved only for humans.

When asked how to promote secularism, Akhtar said that likes and dislikes are not wholesale and that the very idea of a monolith is inherently wrong. “Our history is so distorted that very few have seen it objectively. No ruler can be genuinely communal because they will give anything to him in power. By thinking that any politician is communal is giving him a compliment he doesn’t deserve. They are only addicted to power,” he said.

But perhaps the funniest part of the session was the last question that truly horrified the Afreen Afreen lyricist. He was asked if Sanskrit came before Urdu. Baffled, Akhtar remarked that it was a shocking question, saying “Urdu toh kal ki bacchi hai (Urdu is a young girl)”.

ThePrint is a media partner for the Jaipur Literature Festival 2026.

(Edited by Ratan Priya)