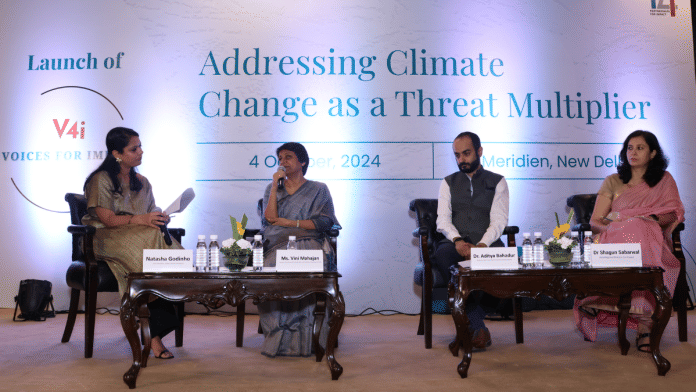

New Delhi: The promise of artificial intelligence is empty if India doesn’t clean up its vast databases. Merely digitising records is not enough. It’s a no-brainer, said IAS officer Vini Mahajan at the launch of the knowledge exchange platform Voices for Impact earlier this month.

“We haven’t used AI tools as we should, even though we have great databases. We’re still not sure if those databases are completely cleaned up,” said Mahajan, secretary, Department of Drinking Water and Sanitation, Government of India, in her keynote speech at Delhi’s Le Meridien.

Even for driving policy action based on data collected from the ground, the verification process must be simplified, she said, bringing attention to the possibility that current digital transformation efforts could become redundant by merely converting manual records into paperless formats.

“Are we leveraging the strengths and competencies of our on-the-ground workers, or are we just digitising paper records, potentially duplicating effort?” she said.

Is AI a solution or a problem?

The potential of AI and the need to harness its power effectively became the focus of a panel discussion with bureaucrats and heads of international non-government organisations weighing in on this. Here, too, Mahajan, underscored the importance of innovation in the information technology sector to improve how data is handled and used.

She called upon audience members—from policymakers to philanthropists—to encourage and support India’s young, dynamic talent pool.

One of the panellists, Shagun Sabarwal, the programme director (Asia) of the London-based philanthropic organisation Co-Impact, urged caution and warned against the overreliance on newer technologies like AI and big data models to solve the climate crisis.

Also Read: Haryana farmers’ AI Jugalbandi, Bengaluru’s Sarvam—West is keenly watching India’s progress

She shared a funny anecdote from an IIT professor, highlighting how people design big complex data models and install sensors to alert citizens in case of potential flooding. Instead, all they need to do is ask the “local chaiwala” a simple question about rainfall and waterlogging, she said.

There’s a trade-off when collating big data and building AI models. They require silicon-based chips. They require water to keep the machinery cool. They need huge amounts of electricity—all of which are finite resources.

“We solve one problem and add another one,” said Sabrawal. “I am not against data or technology. AI has a huge role to play and with technology we cannot [make progress in tackling climate issues],” she added.

In the absence of improved tools and methods, bureaucrats and policymakers often feel alienated from information gathering because climate science has become so complex or technical, said Sabrawal.

Aditya Bahadur, director of Netherlands-based Red Cross Red Crescent Climate Centre, found common ground with Mahajan when he, too, stressed on the importance of data. Good-quality data is the foundation of effective action. Traditional methods of house-to-house surveys are not only expensive but also time-consuming, he added.

“Many times, when support arrives, it’s too late. You’ve lost a lot of lives,” he said, emphasising the need to shift toward newer technologies to save vulnerable sections of society from climate change-associated dangers.

AI to fight against climate change

From food security in East Africa to heat waves in New York, scientists and policymakers are collaborating to find AI-related solutions.

Bahudar pointed out how the United Nations’ World Food Programme (WFP) initiative in East Africa has created an algorithm to predict food security—one of the biggest areas impacted by climate change. The algorithm helps identify who should receive food aid during crises by analysing data, such as cell phone recharging habits below a certain threshold, to estimate calorie consumption within a population.

AI is doing a lot more than just predicting food shortages due to climate change. It’s also helping cities monitor and predict heat waves, which, as Bahadur pointed out, is a much trickier job. In fact, extreme heat is responsible for nearly half a million additional deaths every year, with 31 days of intense heat making a global impact.

Bahadur explained that temperatures in cities vary not just by district but sometimes from block to block, depending on the buildings, roads, and trees in the area. That makes predicting heat in urban areas quite a challenge.

To tackle this, innovators in the US came up with a clever solution to monitor temperatures in New York.

“They’ve figured out how to use cell phone batteries to measure ambient temperatures. In the US half a million mobile phones are now helping track precise air temperature by monitoring their battery temperatures,” said Bahadur.

This doesn’t just provide accurate data for heatwave predictions. It also helps the government focus its resources. Instead of setting up cooling centres in the entire city catering to 20 million people, they can direct aid to neighbourhoods that need it the most.

“The time has come for us to start taking these approaches very seriously and mainstreaming them in decision-making,” he added.

(Edited by Humra Laeeq)