New Delhi: In a world where everyone has a microphone and expertise is optional, Santosh Desai’s Memes For Mummyji: Making Sense of Post-Smartphone India holds up a mirror to the uneasy, fragmented reality of life after the smartphone.

“The idea of expertise collapses when a fact becomes what I believe. If something matches my belief, it is a fact; if it doesn’t, it is false. My judgement, my opinion, becomes central,” said Desai, a columnist and social commentator.

“What is even more disturbing is that if information agrees with me, I don’t care whether it’s fake or not. The very idea that fake news is bad is being challenged. Increasingly, truth itself doesn’t matter. What we want is validation — and that, now, is what passes for truth.”

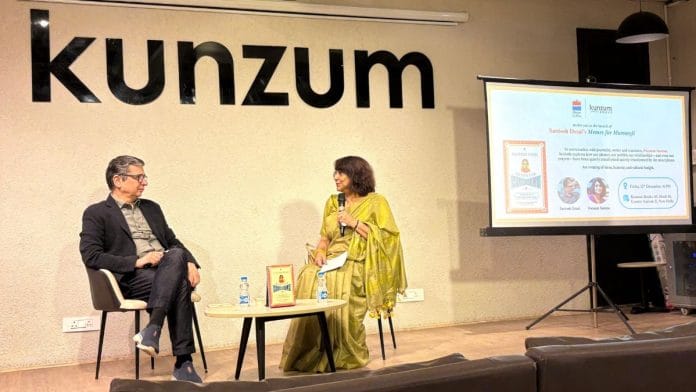

At Kunzum Books in Greater Kailash II on 12 December, Desai launched his latest book. He was in conversation with journalist, writer, and translator Poonam Saxena, as they explored how the digital age hasn’t just changed how we shop, scroll, or connect; it has also reshaped the very fabric of everyday life — from our streets to our living rooms, and even the way we trust truth itself.

Thanks to platforms such as X, YouTube, and Instagram, everyone now has a microphone, and the traditional filters of expertise have all but vanished. Instant expression allows anyone to respond immediately — often anonymously.

“In India, the ‘I’ has always been plural, like grains in a sticky khichdi — we were part of the group. Homes were shared, rooms were communal, meals assumed. Today, as we take ourselves more seriously as individuals, boundaries multiply. Our phones, selfies, even food, all reflect this — everything revolves around ‘me.’ Individualism has turned the simple into the complex, and we live in constant negotiation with ourselves and the boundaries we build,” said Desai.

When advertising moved online

Desai spoke of a time when advertisers worked closely together, creating humorous human stories about everyday life that reflected the collective spirit of the nation. Advertising then, he said, was more than selling products; it was a way for the country to understand itself, offering little vignettes that resonated deeply with people’s experience.

“We create advertising to appeal to people, to connect with them, and in doing so, to relate to their lives. But that connection relied on media that reached everyone at the same time. Once the media became fragmented, that shared experience began to unravel,” said Desai.

Globalisation and technology accelerated the change. Advertising moved online, and the unique charm of the Indian experience began to dilute, as campaigns became part of a global system, crafted to fit international norms rather than local sensibilities.

But the biggest change, Desai argued, is in how people consume media. “When everyone saw the same shows, read the same stories, we were almost a collective. Now, with everyone on their mobile phones, everyone is separate. What advertising used to be is now five crore individual stories. The need hasn’t gone — just the format,” he said.

He observed that technology has turned advertising into a mechanical exercise. What was once a human-centred craft has now become algorithm-driven. Everything is measured and calibrated, with advertisers adjusting knobs to achieve the desired effect.

Also read: Demon Hunters to A Chip Odyssey, Taiwan Film Festival has a message for Indian audiences

True development

This shift goes beyond advertising and reflects broader changes in urban life and the erosion of shared spaces.

Saxena noted the loss of street vibrancy that once shaped collective experience. “One of the beautiful chapters in the book is Diagnosing Our Streets. It shows how a city begins to drown when its streets lose meaning. Today, we sanitise our living spaces — our colonies, our societies — so much that we cut ourselves off from the very life that used to be all around us. To me, that feels like such a pity,” said Saxena.

Desai expanded on this widening gap between urban aspirations and reality. He said that our ambitions have grown, yet cities have lagged.

“Someone will always build something wherever they can. Our cities overflow with that. So, rather than a sense of belonging, which used to dominate, the desire now is to escape the city. In the cinema of the 50s and 60s, the city was romantic, full of challenge and possibility. Today, it’s just a plug-in facility: a place you use for convenience while remaining fundamentally displaced,” said the author.

Urban escape, he argued, is as psychological as it is structural. According to him, the larger problem in India is that the country is growing, “yet not truly developing”. He said development isn’t just roads or airports; it’s about predictability — knowing that at a red light, everyone will wait, or that laws will be enforced, that if something goes wrong at a police station, action will be taken without bribes.

He said this transformation is also reflected in the architecture of digital platforms.

“Digital technology at one level is shallow, but it also has rabbit holes that are very deep. It creates belonging, it creates polarisation. It is individualising, but it creates individuality. Structurally, technology produces contradictory effects,” he said.

These contradictions are more likely to intensify with the arrival of AI. Desai warned that as automation begins to absorb cognitive labour, what remains of us may be little more than our “so-called humanity.” He explained, “Our role will not be to think or act, but to performatively emote, while all substantive work is handled by technology.”

The conversation also turned to the growing reach of the state into digital life, particularly through mobile phones and surveillance. On this, Desai noted that most Indian citizens do not see privacy as a right under threat. Instead, “they see it as security, something that reduces fraud and creates a sense of safety,” he said.

(Edited by Aamaan Alam Khan)