Kozhikode: Can popular history help counter the mass distortion of history in Indian curricula? How do histories of gender and food expand the ways we look at the past? These were the questions three women historians from three generations tackled at an online session during the ninth edition of the Kerala Literature Festival in Kozhikode.

“Given that learners are now much more tech-savvy than what we were, it’s likely that the younger generation will access these resources [platforms such as YouTube]. And it’s not only the textbook on which they will rely on… That, hopefully, will redress some of the issues that we were confronting,” said Kumkum Roy, former professor of ancient history.

According to her, it’s important to engage with ‘troubling’ histories in an era where parts of the syllabus that bring any discomfort or tension are simply erased. Roy hopes that some of it will happen through informal channels.

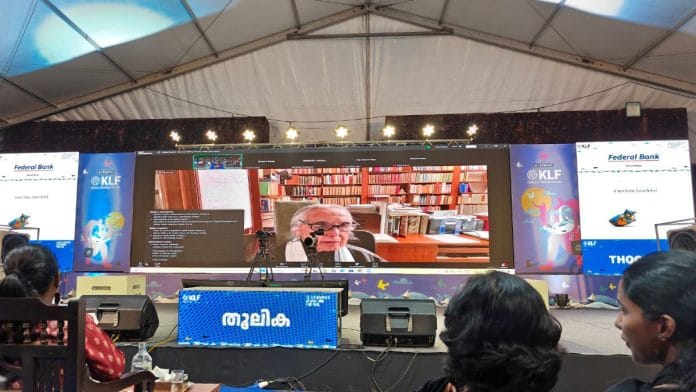

She was joined at the session by historians Romila Thapar and Preeti Gulati on Friday evening. The session, titled ‘Women Writing History: Three Generations’, was moderated by Malavika Binny, Head of the Department of History at Kannur University.

While Thapar called the edits in NCERT history textbooks ‘a nonsense’, she also warned about the reliability of sources and evidence in popular history, which doesn’t follow academic processes of data gathering and documenting.

“The legitimacy of the discipline is being questioned by a lot of what’s generally called popular history that comes on social media… One should be aware of whether one is quoting a statement that comes out of professional historical writing or is a statement which is popularly propagated,” she said, adding that history is a continuous process that shouldn’t be broken.

Gulati shared that she feels tired and besieged by the “continuous clampdown” on institutes such as the JNU and FTII. But she doesn’t view the discipline in the binary of golden era versus dark era, as there are students who still want to study history.

“There are enough people to be reading books, there are enough publishers to be publishing books. Some will be popular histories; some will be reading academic histories,” she said.

Also read: The story of Ranthambore’s 50 iconic years and the ‘Tiger Man of India’

Histories of gender, food

The discussion brought forth a more subtle distortion in history, which reduces the role of women to some select ‘brave woman’ icons rather than analysing systems of power.

Roy traced the journey of history from purely dynastic to socio-economic processes in the 1970s, which allowed women to be seen. According to her, it was a crucial period, with the landmark Towards Equality (1974) report, which forced scholars to document the differential positions of women across domains. And 1975 was celebrated as the International Women’s Year.

“So, when we look in terms of the differences among women and men in terms of caste, class, sexual orientation, disabilities, regional identities, religious identities, and so on, it becomes a much more complex, challenging, and rich process,” she said.

And while women’s studies centres have only grown over the last 40 years, Roy argued that there is a long way to go for gender to appear as a running thread through textbooks, beyond one or two chapters. She added that some areas are even more unexplored, including queer history, which her generation missed.

Gulati’s interest in food began with a childhood act of rebellion: insisting on eating eggs during Navratri. She argued that studying food allows historians to borrow tools from other fields, such as anthropology and sociology.

“I think that is the broader engagement with foodways. It’s not just a sort of question that, you know, should eating beef be allowed? Is beef eating a part of Hinduism? I think the questions are far broader. A historian’s role is a bit more than what I think are very simplistic questions.”

(Edited by Prasanna Bachchhav)