New Delhi: When filmmaker Dibakar Banerjee was making Tees, he was thinking of possible marketing strategies. It included appealing to the audience of Khosla Ka Ghosla!, his 2006 cult film about owning a home in Delhi’s scam-riddled real estate world. But Tees never saw the light of day, much like the protagonist Anhad Draboo (Shashank Arora)’s book on his Kashmiri Muslim family.

“I have made a film about art that tried to be told and not being told, and as I go back and watch the film, I see my past, present and future altogether without intending it to be so. The film wasn’t meant to be autobiographical,” said Banerjee.

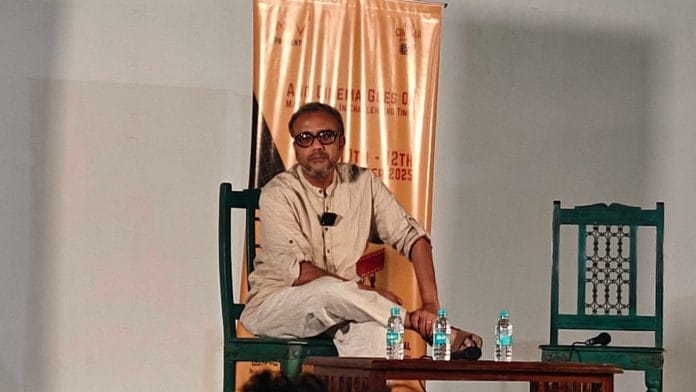

Banerjee’s film was screened in Delhi as part of the inaugural edition of And Cinema Goes On film festival, curated by Labanya Dey. It showcased “suppressed films and resilient voices” from India, Iran, and Palestine, including Sreemoyee Singh’s documentary And, Towards Happy Alleys and Jafar Panahi’s This Is Not a Film.

Tees, commissioned by Netflix, was shelved by the streaming platform after its completion in 2022.

The screening, which had mandatory registration, saw a turnout exceeding the seating capacity of Niv Art Centre’s terrace. The audience eventually spilled into another hall, as people sat down on carpets. The screening, delayed by an hour, ended with a Q&A that went on past 10:30 pm, as everyone jostled to ask Banerjee questions about the film’s making, research, and his reaction to its fate.

The journey

Tees was shelved after the fallout of the 2021 Amazon Prime Video political series Tandav. It had landed the streaming service in trouble, after which the second season of the show was cancelled. In 2022, Tees, too, was shelved. A 2019 blog on Netflix, titled Netflix partners with India’s finest storytellers on 10 new original films, mentions Banerjee’s film, but under its original title Freedom. The other connection between the two is Gaurav Solanki, who wrote Tandav and also worked with Banerjee in Tees.

“Directed and produced by Dibakar Banerjee, it is the story of an Indian family interwoven with the personal, ideological and sexual history of India and how desire plays a common role in each,” reads the description of Tees.

Tees shows the journey of three generations of a family, starting in 1989 before moving to 2019 and 2042. In 2042, Anhad is a sex worker soliciting through an app, but he is also a writer. He is, ironically, the author of Tees, an unpublished book that didn’t see the light of day owing to the stringent censorship rules. The title refers to communal riots in 2030. The film itself opens with the rejection letter being handed to Anhad, and three years after the film’s completion, it mirrors Banerjee’s journey.

“We had extensive conversations with Kashmiri Muslim and Pundit families. The role of food emerged from these conversations.They told us that Kashmiriyat was more important than the language, and we wanted to show it in the film,” said filmmaker Shabani Hassanwalia, who is part of the film’s crew.

The 1989 timeline features two school best friends — Ayesha (Manisha Koirala) and Usha (Divya Dutta) — who are on two opposite sides of the separatist movement in Kashmir. While Ayesha tries to maintain that everything is well in the world, Usha is the one who constantly pokes holes in the fantasy, even making her friend see how the world and their friendship now has irreparable cracks.

For the film’s writers, the research also brought up things about Kashmir that are often lost in the discussions around its troubled history — from how women used to form a major chunk of the Valley’s workforce to the region’s literacy rate.

One audience member — a Kashmiri — mentioned how he identified with the character of Zia (Huma Qureshi), a queer lawyer in Mumbai who struggles to find accommodation because of her identity. In one scene, a broker calls and asks, “Is it Zia or Jia, or Jiya Re?” referring to a song from Jab Tak Hai Jaan (2012). All it takes is a letter to determine her “Mohamedden identity” and she is denied the right to own a house.

“I didn’t even dream of casting Kashmiri actors because I wanted the film to get started,” said Banerjee, responding to a question about him casting people from J&K for the film.

But the director, known for films like Love, Sex Aur Dhoka (2010), its 2024 sequel, and segments in Netflix-backed anthologies Bombay Talkies (2013), Lust Stories (2018), and Ghost Stories (2020) realised he had pushed it too far this time. And that he had to face the consequences.

Also read: Dynasty politics, not patriarchal society, is Haryana’s real challenge: Abhimanyu Singh Sindhu

Resistance

In 2042 India, the gap between the haves and have nots is wide, and people are divided along the lines of caste, religion, class, and political allegiance. Air is not free, and celebratory processions occur only in the underground metro. A recorded voice plays at regular intervals, saying “shaleenta manushya ka abhushan hai (decorum is beauty)”.

It is a creepy, eerie warning against dissent of any kind, even celebrating a wedding.

There is no mention of the ruling party, or of any real-life politician. Tees is just as sensitive to the plight of the evicted Hindus as it is to other minorities. Banerjee actually makes a statement — that everyone, regardless of their political leaning, is in the same boat.

Now, Banerjee is showcasing Tees in non-ticketed shows at film societies for cinephiles and students. It premiered at the Dharamshala International Film Festival last year and was shown at Indian Film Festival Bhubaneswar 2025. It is a form of resistance against the oblivion that shelved films usually fade into.

(Edited by Aamaan Alam Khan)