New Delhi: For close to two millennia, air-dried clay statues have been prominent across the Indian subcontinent, found in India, Bhutan and Bangladesh, but unfortunately haven’t generated much interest among archaeologists.

The Bamiyan Buddhas, for example, were two colossal clay structures from the sixth century in Afghanistan that were destroyed by the Taliban in 2002. Other famous clay statues in the subcontinent are in Bhutan’s Thangtong Dewachen Nunnery from the 19th century.

“South Asia has a long-standing and widespread practice of earthen sculpture in air-dried painted clay. And yet, remains barely noticed in publications on the region’s art and is absent from most museum collections,” said Susan Bean, curator and chair of the Advisory Committee of the Art and Archaeology Centre of the American Institute of Indian Studies.

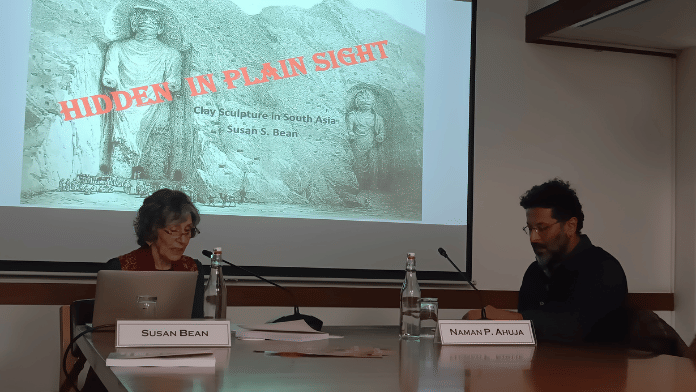

She was delivering her lecture titled ‘Hidden in Plain Sight: Clay Sculpture in South Asia’ at the India International Centre on 12 February in New Delhi. The session was well attended by art historians, along with students and teachers from the National Institute of Fashion Technology.

Art historian and Jawaharlal Nehru University professor Naman Ahuja moderated the talk and emphasised how Bean’s work focuses on the material discovered from the subcontinent in the past two centuries.

“Good art and great art is not something that is predicated on being made permanently out of stone. But it is made out of material which is inexpensive enough for you to be able to remake every time a monsoon washes it away,” said Ahuja.

He asked Bean about the use of lime mortar and cow dung for making sculpture.

“It’s a very common material in use especially in Bengal for sculptors to mix dung with clay. In Gandhara sculpture they use horse hair in the armature,” she said.

In her 45-minute long lecture, which followed the talk, Bean took the audience through images of some of the most prominent practices across the region to consider why painted air-dried clay has been so valued as a medium for figural sculpture. She further delved into the meaning and reasons behind the absence and sidelining of the art reveals.

Given the millennia-long prominence of painted terracotta sculptures across the region, Bean said that it is surprising that it is still nearly absent in publications and exhibitions.

Bean gave two possible reasons for this: “First, the enormous influence of European ideas about sculpture. Second, in Indian art history, the long preoccupation, for very good reasons, with iconography, chronology, and style, sidelined the significance of materials.”

Also Read: ‘Illegally removed’—India to bring back three ancient bronze sculptures from Smithsonian museum

Buddha and the clay statue

Buddhist polychrome air-dried clay statues have continued to be made across the Himalayas and continue most actively now in Bhutan.

“In Bhutan, the practice is focused on creating Buddhist statues that will be kept for as long as possible,” Bean said.

Bean spent the last five decades researching clay sculptural traditions and history across the subcontinent.

“Indic cosmologies recognise earth as a fundamental constituent of the universe,” she said.

Bean mentioned the 1971 book The Indian Technique of Clay Modelling by KM Varma who refers to the Agama and Shilpa Shastra texts dating between the 10th and 16th century.

“There he found ample guidance on processes for preparing clay and constructing an image in polychrome terracotta,” she said.

Bean said that the terracotta sculpture continues to be most vigorously pursued in the Deccan and in the eastern subcontinent as temporary festival imagery that is immersed in observance.

In India, Ahuja noted the fragility of the clay sculptures referring to an excavation by Alexander Cunningham at Bodhgaya, Bihar and said that it was a common problem at such sites. When Cunningham first excavated the site all the Gupta period ganas (terracotta panels) disappeared, Ahuja added.

“They have survived the centuries. We have a photograph but the object itself is no longer,” said Ahuja.

In Bhutan, clay is preferred for Buddhist sculpture because earth contains all precious substances, Bean added that moist clay can develop and envelop ground gems, medicinal herbs, and ashes, conveying the powers of these into a statue, enhancing its spiritual energy.

She cited the former director of the National Museum of Bhutan, a Buddhist monk, who said that this capability of clay to contain precious substances elevates the sacred value of a single raw clay statue to the equivalent of a thousand statues of gold.

“As earth, clay is linked to life and fertility. The very material can bring a living presence into a statue. Sculpted images of deities and portraits of heroes and kings are imbued with the presence of the being they represent,” she said.

Bean added that all of these items are made for communities. “Their visual value system is crucial for understanding any kind of art practice within its context.”

(Edited by Insha Jalil Waziri)