Bengaluru: Bengaluru, celebrated as India’s tech capital, thrives on innovation and cutting-edge advancements. Yet beneath this high-tech facade lies a persistent issue that has haunted the city’s image for years—traffic congestion. In 2024, it was ranked as India’s second slowest city in terms of traffic. In response, the Bangalore Traffic Police inaugurated a new museum to showcase their valour, achievements, and pride.

From holding a lantern between sunset and sunrise to alert drivers of potential hazards to today’s AI-powered traffic lights and smart cameras equipped with facial recognition technology—the newly inaugurated Traffic Police Museum and Experience Centre on Infantry Road documents the evolution of traffic policing in Bengaluru over the years.

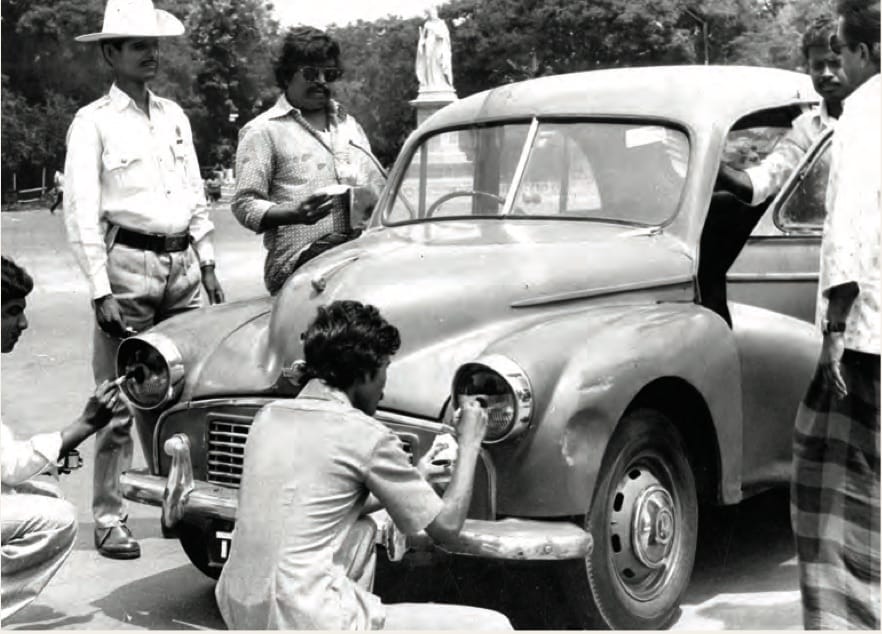

The museum’s walls are adorned with photographs of vintage portable radar equipment, khaki uniforms, patrol vehicles, and other historical artefacts tracing the city’s traffic management journey.

From relying solely on hand signals in the 19th century to now incorporating AI and technology-based systems, Bengaluru’s traffic management has come a long way. The traffic museum, the first of its kind in the city, takes visitors on this journey through time. Similar museums exist in Delhi, Chennai, and Jaipur.

“By showcasing the history and development of traffic management, the traffic museum aims to promote road safety awareness, educate citizens about traffic rules, and inspire a sense of appreciation for the tireless efforts of traffic police personnel,” said Joint Commissioner of Police (Bengaluru Traffic) MN Anucheth while inaugurating the museum on 29 January 2025.

- The Bengaluru traffic museum chronicles the evolution of traffic policing in Bengaluru.

- Exhibits range from historical lantern signals to modern AI-powered traffic systems.

- Displays include vintage equipment, uniforms, and archival photos.

- A tribute to the dedication and heroism of Bengaluru’s traffic police.

Also read: Tattling to bosses of traffic violators won’t solve Bengaluru’s gridlock. It will hurt jobs

A journey through time: Inside Bengaluru’s traffic museum

At the General Post Office (GPO) traffic signal on Ambedkar Veedhi Road in Bengaluru, constable Marichikaiah Thimmaiah’s statue stands tall, a silent tribute to his dedication. Nearly four decades ago, Thimmaiah stood at the same signal post every day for 19 years, using hand signals to direct traffic—until he died in 1995 while trying to save a woman and her child from being run over.

A black-and-white photograph of Thimmaiah and his tireless service now finds a place in the Bengaluru traffic museum.

Karthick, a 22-year-old postgraduate student at Government Arts College, regularly crosses Thimmaiah’s statue on his way to class. “I always noticed his thick moustache, but I never knew his brave story until today,” he said after visiting the museum between lectures.

Before Bengaluru’s tech boom—when it was known as Bangalore Town in the 19th century—policemen relied solely on hand signals to manage vehicular traffic. It was a labour-intensive task that required constables to stand under the scorching sun or heavy rain for long hours.

The city’s first traffic signal with a countdown timer was installed at Cauvery Theatre Junction on Bellary Road in 1999. Until then, police constables managed traffic manually round the clock.

Near these displays, a small newspaper clipping from The Hindu’s Bangalore edition in 1972 is showcased. “The idea is to avoid, as far as possible, the tedium of manual control of traffic…At least 68,000 vehicles are plying at the moment,” then-Deputy Commissioner of Police (Traffic), C Dinakar, told the paper in the lead- up installing automatic traffic signals.

In earlier years, enforcing traffic rules meant physically stopping offenders. One archival photograph from 1973 in the museum shows a policeman blackening the headlights of a car as punishment for speeding.

“Today, we are just asked to pay a fine and the police will let us go. But it doesn’t stop offenders from repeating the mistake. Blackening headlights seems like an innovative way to curb speeding,” said Rahul Joshi, a 27-year-old chartered accountant.

In cases where fines were required, offenders were taken to ‘mobile courts’. Established in 1974, these courts operated out of small vans where a magistrate reviewed cases and imposed penalties on the spot.

Another museum visitor marvelled at these historical methods of traffic management. “Being a police officer in those days would have been tough. I always thought that without today’s technology, our traffic system would be chaotic. It must have been incredibly challenging to maintain order with just basic tools and manual effort,” said Vijay Sai, a 45-year-old IT engineer.

From lanterns to AI: The evolution of Bengaluru traffic policing

From just 68,000 vehicles in the 19th century to approximately 28 lakh vehicles today, Bengaluru’s traffic has become a monumental challenge. Manual traffic management could no longer keep pace with the city’s growth.

Like many sectors in the city, the Bengaluru Traffic Police turned to technology. The museum carefully separates displays of antique equipment from exhibits showcasing modern advancements.

In one corner, a mannequin is dressed in a simple khaki shirt, pants, and helmet—standard police attire in the 19th century. Nearby, another mannequin dons a white shirt, brown pants, a walkie-talkie, and a body camera—today’s standard uniform. Currently, 4,725 such body cameras with facial recognition technology are in use, with 300 of them live-streamed and monitored in real time at the traffic police’s ‘Smart Enforcement Centre’.

Another significant advancement is AI-powered traffic signals. A large screen in the museum displays a digital map of Bengaluru, marking the 103 AI signals installed across the city.

In 2024, Bengaluru became the first Indian city to adopt AI-based signalling and digital enforcement systems to ease congestion. Installed at choke points like KR Road and Hudson Circle, these AI signals analyse vehicle density in real-time and dynamically adjust traffic light timings to improve movement.

“This system has reduced unnecessary delays and optimised traffic flow, particularly during peak hours. Based on our calculations, AI signalling has significantly lowered travel times by 17-22 per cent,” said Anucheth.

Despite widespread acclaim for AI-driven traffic management, some museum visitors remained sceptical. Some even expressed a newfound appreciation for traditional methods.

Murali, a 22-year-old college student, noted longer pedestrian wait times at signals.

“Ever since AI signals were introduced, I have had to wait at least four minutes for the pedestrian sign to turn on at Corporation Circle. The old systems were faster,” he said.

(Edited by Prashant)