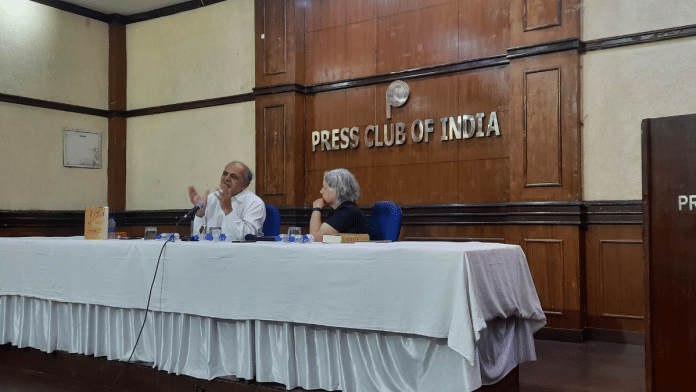

Is there a single past or many pasts? This was the most important question at Delhi’s Press Club of India on a Sunday evening. Braving the monsoon humidity, a large crowd comprising academicians, students, writers, journalists, and heritage and history enthusiasts thronged the conference room to hear renowned literary critic GN Devy talk. The professor was in conversation with the famous linguist Peggy Mohan. The topic? An Aleph Book Company publication edited by Devy, Tony Joseph and Ravi Korisettar — The Indians: Histories of a Civilization.

Launched in July 2023, the 620-page book has become the talk of the town in academic circles. The ambitious project is a culmination of 101 essays written by nearly 100 scholars, covering a magnanimous time period of about 12,000 years — from the Ice Age to the 21st century.

In a political atmosphere where history is being moulded into a unitarian version, Devy’s book is a fresh attempt to document the pluralistic narratives of the people who have inhabited the subcontinent over the millennia. The Indians tries to answer the question that has become a hot-button issue for many politicians: What is the history of India and its people?

Also read: Eight step wells, 2 cities, 10 years—how collaboration revived crumbling Mughal ‘baolis’

12,000 years, 101 chapters

Right at the start, Devy made it clear that The Indians offers its readers an off-beat version of history.

“This book is not about kingdoms and nations, it is about people of India. It is a history of pluralism, of acceptance, of continuity,” he said. “We wanted diversity to appear, therefore we chose the title ‘histories’ of a civilisation…This is not a history, it is histories.”

Anxieties about the current political climate weren’t amiss.

“It is such an unusual book and put together in such a different way at a time like this — when we are quite disturbed over a lot of things in the intellectual sphere,” Mohan said.

And The Indians isn’t a boring or heavy academic book — it’s a light, enjoyable read that draws you in. Describing the book as ‘necessary’, Mohan called it “a wedding feast”. “I treated it as a tasting menu because I immediately went through [it] and marked my favourites and read them first, in a very matlabi way,” she added.

The Indians’ approach to history is unique in two aspects — in terms of diversity and linearity of the narrative. “We had decided on two backbones. One is diversity: Let people tell their stories the way they want to. Second was varying timelines…India does not have straight timelines,” Devy said.

In the grand corpus of the Indian subcontinent’s history, Devy says it is only natural that scholars would have missed documenting the history of certain populations. This is the gap that the professor wanted to plug. “Three things are missing, [which] I want to add — Kashmir, Nomads, and sea life,” he added.

Also read: Hindu Varanasi or Mughal Banaras? A Toronto professor wants you to look at hidden…

Not a ragda pattice

In 2020, the Union Ministry of Culture set up a committee of experts to conduct “a holistic study of the origin and evolution of Indian culture since 12,000 years before present and its interface with other cultures of the world”. It seemed a laudable endeavour to many. But as the details about the committee came to light, a different story unfolded. “There was nobody from the South, no women, nobody from the Northeast, no Muslim, Christian, Parsi, or Sikh,” said Devy. “It only had people of one social community, caste…all from a restricted area.”

Devy decided to embark on a similar project, which was to materialise in the form of The Indians. In 2010, he carried out the People’s Linguistic Survey of India (PLSI), trying to document all living Indian languages. This time, Devy reached out to linguists, historians, archaeologists, genetic experts, philosophers, and social scientists for their insights. “I wrote to them, as many as I could,” the professor recalled.

To his surprise, many responded. “There is a word in German — zeitgeist or spirit of the time. It was the spirit of the time that was speaking through them.”

The book thus features the works of scholars whose concerns and spirit aligned with Devy. “I realised that there are scholars, and scholars in all fields, who all feel worried that knowledge is being used as a weapon for social redefinition and division.”

As Devy, Joseph, and Korisettar sat down, they divided the broad time period into 100 sections. “We hadn’t initially decided on such a rigid division, it just happened naturally,” said Devy.

They would soon realise that navigating with such a large variety has challenges too. “We did not want to make a Ragda Pattice…it is a dish where nothing remains in its original form,” added the professor.

A glorious 12th century

In The Indians, Devy has penned the introduction, a chapter on Varna and Jati, and another on Bhakti.

“I think it was pretty brave of you to come out and say that Sultanate and Muslim presence in India had a lot to do with breaking the end of a decaying Prakrit era,” said Mohan. “In the Bhakti era, the Central Asian sultanates gave space to a whole new expression that was not elitist. So, the new Indian languages came up that way.”

Around the same time, India started using paper. And that was a revolution that still doesn’t parallel anything in human history.

“It was a technological revolution far deeper, far more impactful than IT revolution…Use of paper implied that language monopoly (by the rich) had gone. It was a great moment of democratisation of Indian society,” Devy further commented.

Yet, the great Bhakti saints of the time, including Kabir, Tukaram, Meera, and Jaidev, followed the oral tradition. “There are a lot of enigmas and perplexing questions in our history that have no answers,” the professor added.

In The Indians, Devy shows how “this 12th century was the most revolutionary century for the entire world.”

The way ahead

To Devy, it is essential that the book reaches a larger readership. The Indians is currently being translated into Marathi, Malayalam, Gujarati, Kannada, Tamil, and Hindi. “If the book is most read in Hindi-speaking areas, then not only will I get more royalty, but it will also help fulfil the intent behind the book,” the professor said. He also intends to record podcasts.

And he wants younger people to read the book, remarking how, due to the power of forwarded messages and ‘WhatsApp University’, “the new generation is not just in duvidha, but rather tridha, chaudha” when it comes to history.

At PCI, Devy’s satirical take on the political use of history drew a range of responses — from genuine concerns to outbursts of laughter as well as silent disagreements.

“We can, to some extent, afford notebandi, but itihaasbandi is very dangerous,” said Devy.

(Edited by Humra Laeeq)