Sarnath (Varanasi): Since childhood Pradeep Narayan Singh, a member of the erstwhile royal family of Banaras, had carried the weight of colonised history. One word about his ancestor at the Buddhist stupa in Sarnath haunted his family for two centuries. And that word was ‘destroyer’, written on a plaque outside the Dharmarajika Stupa. It was a source of constant shame and then came a point where he couldn’t ignore it anymore.

The plaque once read that his ancestor Babu Jagat Singh, the diwan of Maharaja Chait Singh, had destroyed the 3rd-century BCE Dharmarajika Stupa to collect building material. But Jagat Singh wasn’t the 18th-century maharaja’s diwan — he was his cousin. And the “destruction” was actually a discovery of India’s oldest Buddhist relic sites. British accounts, however, froze that misrepresentation in time.

It was an incorrect portrayal that cast a long shadow on the royal family. So Singh launched a revenge drama like no other—against history itself.

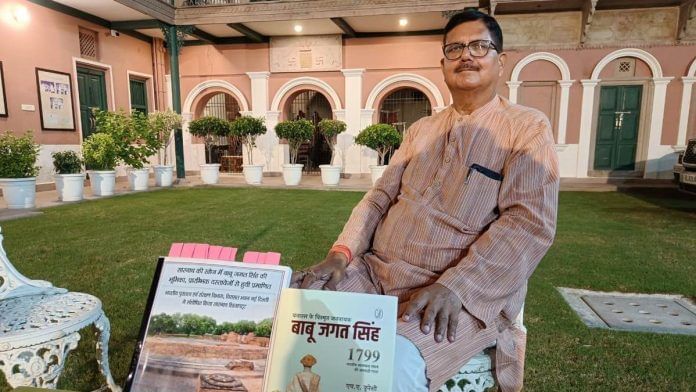

“Since my childhood, I have heard and read negative things about my ancestor. He was portrayed as a villain in history and for us in the family it hurts. We wanted to change this with evidence,” said 63-year-old Singh, sitting in the lawn of Jagatganj Kothi in Varanasi.

To clear that generational stigma and redeem his ancestor in history, Singh embarked on a painstaking five-year hunt through archives in India and Britain. His efforts finally prompted the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) to revise the official plaque in January. It now recognises Jagat Singh not as a vandal, but as the first to uncover Sarnath’s buried past. Not just this, the ASI is also planning to change the main plaque at the site’s entrance to credit Jagat Singh for revealing Sarnath’s importance rather than a lineup of British archaeologists.

As India pushes for Sarnath—where Buddha gave his first sermon after enlightenment—to be listed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site, Singh’s battle to decolonise his family’s history mirrors a larger movement by PM Narendra Modi’s government and the ruling BJP to correct colonial distortions in India’s historical narrative. It was both a personal battle as well as a nation’s counter to British colonial injustice. Singh’s campaign ended centuries of waiting.

“The new scholarship which emerged after five years of hard work changed the history of Sarnath. Once, Jagat Singh was portrayed as the destroyer, now it is changing. The actual history of the site came before the world. The history of Sarnath is incomplete without Babu Jagat Singh,” said Singh, who leads a research team under the banner of Jagat Singh Royal Family Project.

For Singh, the project is both vindication and proof that history can still be corrected — if one has the will to dig deep enough.

Also Read: India’s new search for Hindu warrior kings to celebrate. Vikramaditya, Suheldev to Agrasen

Family battle to correct history

For more than 200 years, no one in Singh’s family had tried to correct the story. Even he hadn’t until his late 50s. In Varanasi, he said, people always knew the inscription was a mischaracterisation and called his father “Raja Saheb”. Beyond those local circles, though, the colonial version endured.

In 2018, when his father died, it finally galvanised him to confront the family’s distorted past. The cultural climate was also ripe for it.

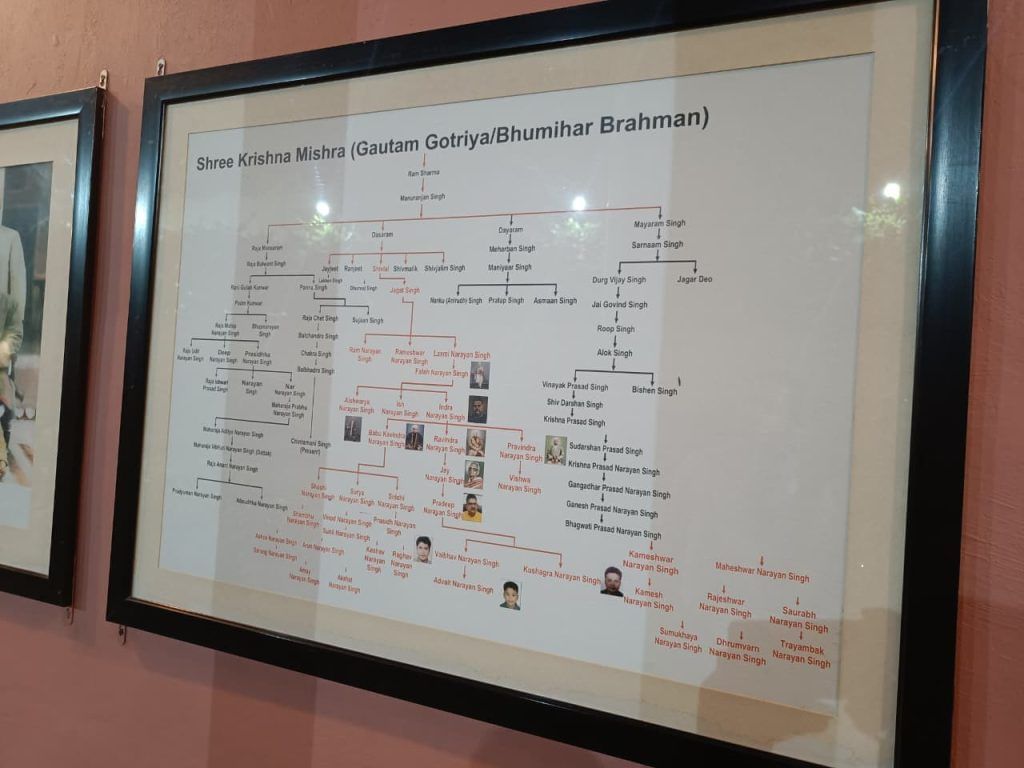

“It was very difficult to start and search for the history as we have no detailed accounts of our ancestors. But I had the will and an inspiration from PM Modi as he talked about finding India’s unsung heroes,” said Singh, pointing to the family lineage chart hanging on a pink wall of Jagatganj Kothi.

Singh, who runs a hotel in the Jagatganj area of Varanasi, has no formal training in history. Yet his zeal to correct his family history led him to scrutinise archives and rare books. Now the wording from ASI reports by Alexander Cunningham and Daya Ram Sahni is at his fingertips.

“From day one I wanted this search to be done in a professional manner. So I decided to bring historians and academicians on board who had the right expertise,” he said, adding that he didn’t want to hurry the process.

The historical redemption expedition started in 2019 with a small group — retired BHU professor Rana PB Singh, advocate Tripurari Shankar, and a few of Singh’s close friends. Together, they launched what came to be known as the Jagat Singh Royal Family Project.

Rana recalled that the first meeting took place at Tripurari Shankar’s house in 2019. No one was sure anything would come of it.

“The journey started then and is still going on. With each passing day new facts about Jagat Singh come to light,” said Singh, a retired professor of geography who has written several books on the landscape of Varanasi and Sarnath.

Recently, the search committee found a two-page letter written by Jagat Singh in Persian, dated 1787, which showed his knowledge of the language. “We got this letter at the National Archives of India (NAI). Jagat Singh wrote to the foreign department of the East India Company,” said Singh.

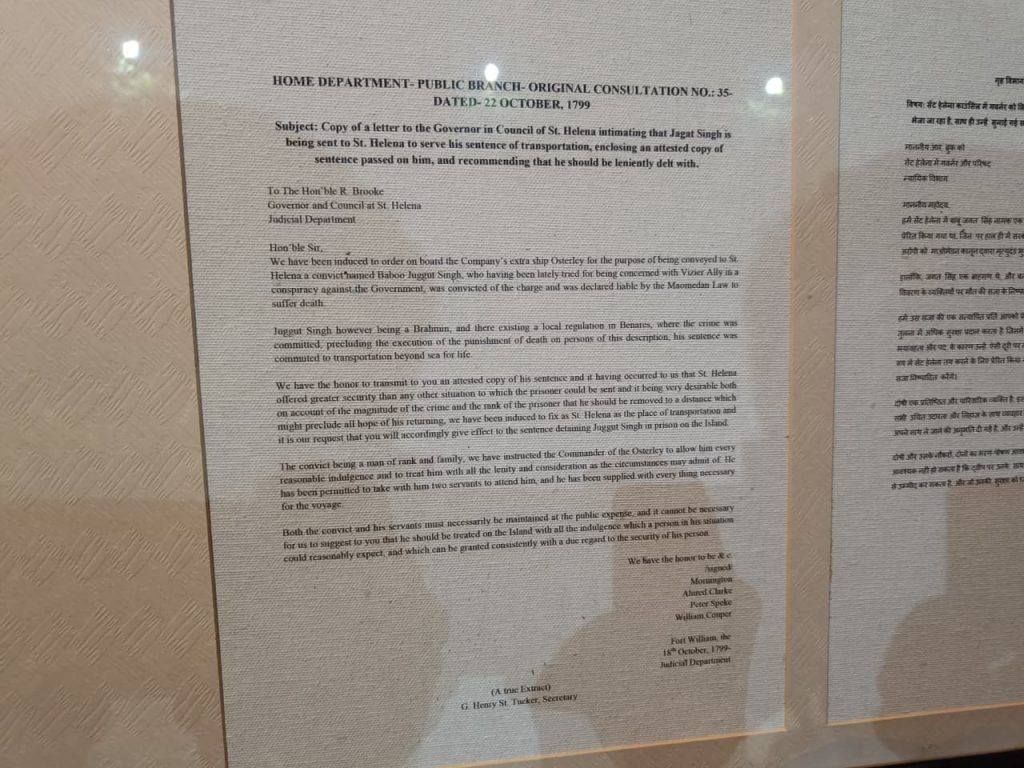

The team also unearthed documents from the British Library in London related to a conspiracy case against him related to a rebellion he led against the British in 1799.

“Babu Jagat Singh was convicted of conspiracy against the government and also of writing letters and sending messages to Jagannath Singh for the purpose of gathering troops,” reads one of the proceedings of the Banaras Nizamat court dated 22 July 1799.

An unknown rebel

To wade through piles of old records and complete the story of Jagat Singh, Shreya Pathak, an assistant professor at Vasanta College for Women, was brought on board as lead researcher.

Pathak spent four years combing through Indian archives before submitting her draft in 2023. She said she visited the NAI, the Uttar Pradesh and Bengal state archives, and the regional archives of Allahabad and Varanasi.

“Most of the documents I found were from the foreign and political department of the East India Company,” said Pathak. But when she searched for records about the 1799 uprising, materials were scarce.

“Many documents are missing. I got only the final judgment of the trial but the documents of the proceedings were missing. Also, nothing has been found regarding the allegations on Jagat Singh”, said Pathak. “But he revolted against the British and Banaras was free for 15 days,” said Pathak.

Singh, however, was not satisfied. He wanted something more concrete. He then contacted historian HA Qureshi, author of Flickers of an Independent Nawabi: Nawab Wazir Ali Khan of Avadh—a book that contained some details about Jagat Singh’s role in the revolt.

Singh met Qureshi at his Lucknow residence and invited him to Varanasi. Soon after, Qureshi came on board as mentor to the project and the lead author of The Lost Hero of Banaras: Babu Jagat Singh, which was published last year by Primus Books.

The online description of the book states that it “focuses on an armed anti-British struggle in Banaras in 1799, pioneered under the auspices of Jagat Singh”. It also credits him with discovering the Dharmarajika Stupa at Sarnath — a finding long “erroneously ascribed to Alexander Cunningham in colonial historiography.”

With the book, the result of his descendant’s obsession, Jagat Singh was elevated from footnotes and implied villainy on a plaque to a hero and a discoverer.

“A desire to pay tribute to his ancestors inspired [Pradeep Narayan Singh]. Otherwise, who would undertake the difficult task of collecting, compiling, and interpreting these scattered sources,” wrote Dhrub Kumar Singh, history professor at BHU in the preface.

From the outset, Singh insisted on relying on primary sources such as letters and official records.

“I have contacted archives of Bengal, Delhi, Lucknow and even the British Library. Finding one piece of paper [on the resolution of the case against Jagat Singh] from the archives took months. But I never lost my patience,” said Singh.

“I have spent Rs 21 lakh on this historic hunt, from India to Britain,” said Singh. But to him the real vindication came when the ASI erased the accusation on the Dharmarajika Stupa plaque.

Research that changed Sarnath’s history

Singh recalled visiting Sarnath as a child and seeing the plaque that read that “diwan” Jagat Singh had destroyed the Dharmarajika Stupa for construction material. There is uncertainty about when the plaque was installed, though it was likely put up after the Sarnath Museum was established in 1910.

“This was incorrect — Jagat Singh was not the Diwan of Chait Singh. They were cousins. In the new plaque, the ASI corrected this mistake on the basis of our research,” said Singh, showing a copy of an ASI letter in which its joint director general Praveen Kumar Mishra instructed Sarnath Circle officials to change the description of the Dharmarajika Stupa.

“You are requested to prepare a fresh CNB [Cultural Notice Board] accordingly on a solid material tuning with the monument’s nature and fix this at a suitable place under information to this office at the earliest,” reads the letter.

In July 2024, Rana PB Singh wrote to the ASI director general urging that Sarnath’s history be corrected in light of the evidence presented in The Lost Hero of Banaras.

His letter stated: “Babu Jagat Singh was the explorer and conservator of the Dharmarajika Stupa at Sarnath in 1787, not a destroyer as erroneously propagated by the British.”

After months of pressure on the ASI to act on the new findings, a revised plaque was finally installed in January this year. It now says that “the stupa came to light in 1794 when labourers engaged by Babu Jagat Singh to retrieve building materials came across a relic casket of green marble inside a stone box.”

The family organised a press conference at Jagatganj Kothi to welcome the ASI’s move.

“This stone plaque is a tribute to the people of Kashi and an honour for the struggle of the research committee. This research has required the utmost diligence. We faced disappointment at times, but we never gave up. If history is properly explored, many heroes and heroines will emerge,” said Singh.

The plaque change was widely covered in the local press. One headline read, Kashi me badla Sarnath ka itihas (History of Sarnath changed in Kashi). Another declared proudly, Angrezo ne nahi, Banarasi raja ke parivar ne karayi thi Sarnath ki khudai; phir se likha jaega itihas (Sarnath was excavated not by the British but by the family of a Banarasi king; history will be rewritten).

Behind the scenes, the ASI went through a detailed internal review process before making the change.

“In the ASI, changing the description of a site is complex. We rely on historical records and ASI reports when we write descriptions of monuments. The same applied to Sarnath. But when new archival evidence emerged, we revised the entry on Jagat Singh,” said a senior ASI functionary on condition of anonymity.

Singh’s team pored over ASI’s annual reports, the writings of Jonathan Duncan—the East India Company’s Resident in the late 18th century— and the archives of the Asiatic Society of Bengal.

According to documents of the Asiatic Society of Bengal accessed by ThePrint, Jagat Singh’s workers began digging in 1787, but the stupa itself came to light in 1794. A green manjusha (relic casket) filled with treasure was sent to Jonathan Duncan.

One of the most compelling pieces of evidence came from Cunningham’s Four Reports Made During the Years, 1862-63-64-65, which explicitly refers to the “site of the stupa excavated by Jagat Singh”. The archaeologist also wrote about coming in contact with one Sangkar, an old man who’d been a boy during that first discovery.

Sangkar told Cunningham that he had helped Jagat Singh and witnessed the unearthing of two boxes — an outer one of common stone and an inner cylindrical one of green marble.

“The contents of the inner box were 40 to 46 pearls, 14 rubies, 8 silver and 9 gold earrings (karn phul), and three pieces of human arm bone. The marble box was taken to the Barâ Sâhib (Jonathan Duncan),” wrote Cunningham.

With Sangkar’s help, Cunningham located what he assumed to be the same stone box and presented it, along with about sixty statues, to the Bengal Asiatic Society, where it was catalogued under his own name.

Cunningham, in his report, noted that Duncan claimed to have submitted the treasures to the Asiatic Society of Bengal. But Singh’s research suggests he never did, and that all the treasures are now missing.

“It is believed that Duncan had given it to the Asiatic Society, but a search conducted about two years ago found no trace of that marble casket,” said BR Mani, a veteran archaeologist who excavated Sarnath in 2013-14. “The British authorities mishandled the green casket which is missing even today.”

Also Read: A British man visits the National Museum and kicks off a debate on colonialism

A freedom fighter is crowned

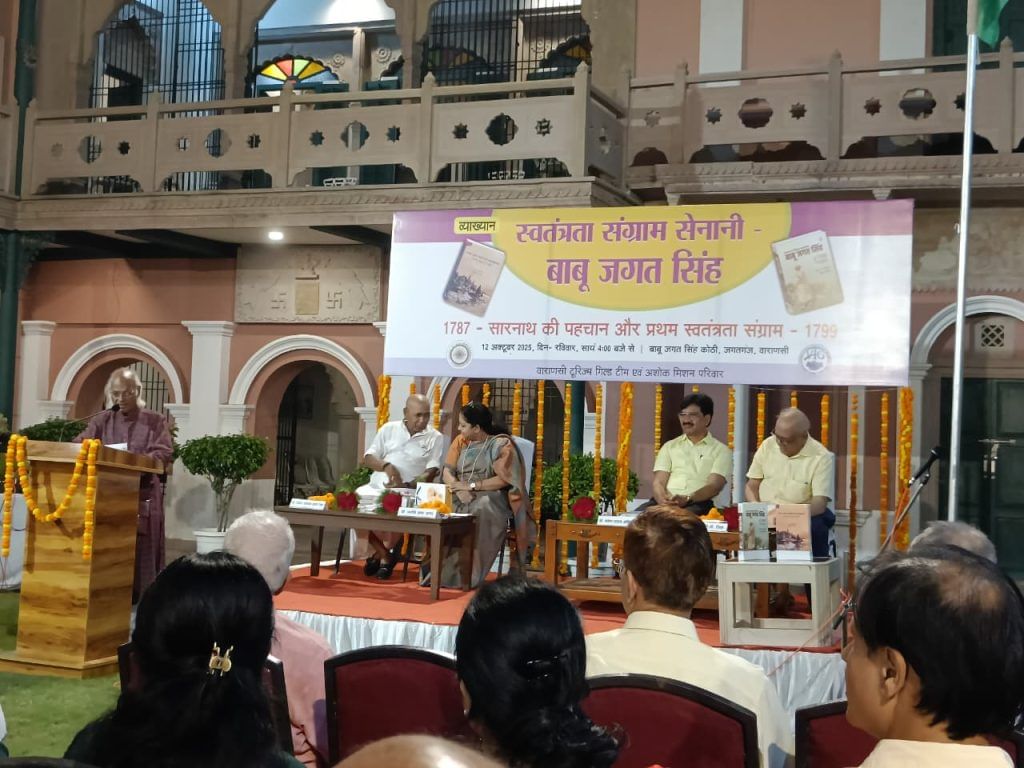

On 12 October, around 200 people gathered at Jagatganj Kothi to celebrate the legacy of Babu Jagat Singh. The lecture added a new layer to his story — portraying him as a freedom fighter who led an early rebellion against the British in 1799.

The lecture, attended by several BHU professors, had a lofty title: Swatantrata Sangram Senani: Babu Jagat Singh, 1787 – Sarnath ki Pehchan aur Pratham Swatantrata Sangram 1799 (Freedom Fighter Babu Jagat Singh, 1787 – Sarnath’s Identity and the First War of Independence, 1799).

The new narrative goes that after Nawab of Awadh Asaf-ud-Daula died, his son Wazir Ali ascended the throne in 1797, but the British plotted to remove him.

“He fled to Kashi, met Jagat Singh, and planned a revolt in 1799 in which five British officers were killed,” said Arvind Kumar Singh, a member of the research committee.

Subsequently, Wazir Ali left the city, but Jagat Singh stayed behind.

“The British took two months to arrest him,” said Arvind Kumar, adding that Jagat Singh was captured at Jagatganj Kothi itself the same year.

He was sent first to Chunar jail and then sentenced to imprisonment on Saint Helena, the remote South Atlantic island that later became Napoleon Bonaparte’s place of exile. Before he could be taken to Saint Helena, Jagat Singh ended his life by jumping into the Ganga River in Bengal.

At the Jagatganj Kothi — which Pradeep Narayan Singh has renovated — documents and British-era letters pertaining to Jagat Singh are now framed on the walls.

On the first floor is the room from which the British arrested Jagat Singh. Adjacent to it, a new library contains yet more archival records.

“The British rulers declared Jagat Singh anti-British, the leader of civil disobedience, and the destroyer of the sacred site of Sarnath. This narrative somehow cast his contributions into shadow, even 77 years after Independence,” reads a review by Rana PB Singh and Priyanka Jha in the journal Space and Culture.

History long warped by the British is now being righted, according to some historians.

“This can be understood in the context of decolonising India’s past,” said Jyoti Rohilla Rana, professor of history and art at Banaras Hindu University. “We still have a colonial hangover. Decolonisation brings cultural pride — indigenous sources are needed for this. Jagat Singh’s history can be seen in this context.”

For Rana, replacing the plaque represents more than a factual correction.

“It’s a significant contribution in itself to providing a proper platform to our lost heroes,” he said.

The event was organised just weeks after a team from the International Council on Monuments and Sites (ICOMOS), an advisory body to UNESCO, visited Sarnath as part of India’s nomination process for World Heritage status. Last year, 8.4 lakh tourists visited the site.

Pradeep Narayan Singh met the visiting officials and gave them documents connecting his ancestor’s role in unearthing Sarnath’s archaeological importance.

Now the corrected legacy of Jagat Singh resonates across Varanasi city as well. Last year, Ravindra Jaiswal, a minister in Yogi Adityanath government, inaugurated the Jagat Singh Dwar, a commemorative installation in Jagatganj stating: Shaheed Babu Jagat Singh Dwar — January 1799 me Angrezon ke khilaf huye Shastra Vidroh ke Nayak (Martyr Babu Jagat Singh Gate — Hero of the Armed Rebellion against the British in January 1799).

“The effort made by the Jagatganj royal family to uncover the history of Babu Jagat Singh and bring it to the public is historic. Jagat Singh is a priceless treasure not only of Kashi but of the entire nation,” said Jaiswal at the inauguration.

This campaign to restore Jagat Singh’s name is extending to classrooms as well. BJP leader Murli Manohar Joshi wrote to NCERT director Dinesh Saklani, urging that the story be included in textbooks. Joshi sent Saklani a copy of the book on Jagat Singh along with his request.

“This book will be available for purchase and reference in the NCERT library. This will also be brought to the attention of the textbook development committee, and the available evidence will be appropriately used in the books,” Saklani replied to Joshi.

With the success of the historical project, members of the research team are now demanding a PhD degree for Pradeep Narayan Singh.

“He deserves a PhD for his outstanding research,” said Rana PB Singh at the event, as the audience cheered.

But Singh’s quest isn’t over. He noted that the Modi government this year brought home the Piprahwa gems—relics linked to the Buddha—after they were nearly auctioned off by Sotheby’s. But the stones and pearls from Sarnath Dharmarajika Stupa are still missing.

“We will continue our efforts until we find them,” he said.

(Edited by Asavari Singh)