New Delhi: The floods that ravaged Uttarakhand’s Dharali village, bringing down 148 buildings, struck without warning. How could authorities have anticipated extreme weather events like these? Region-specific flash flood and cloudburst warning systems, if the Himalayan belt had any.

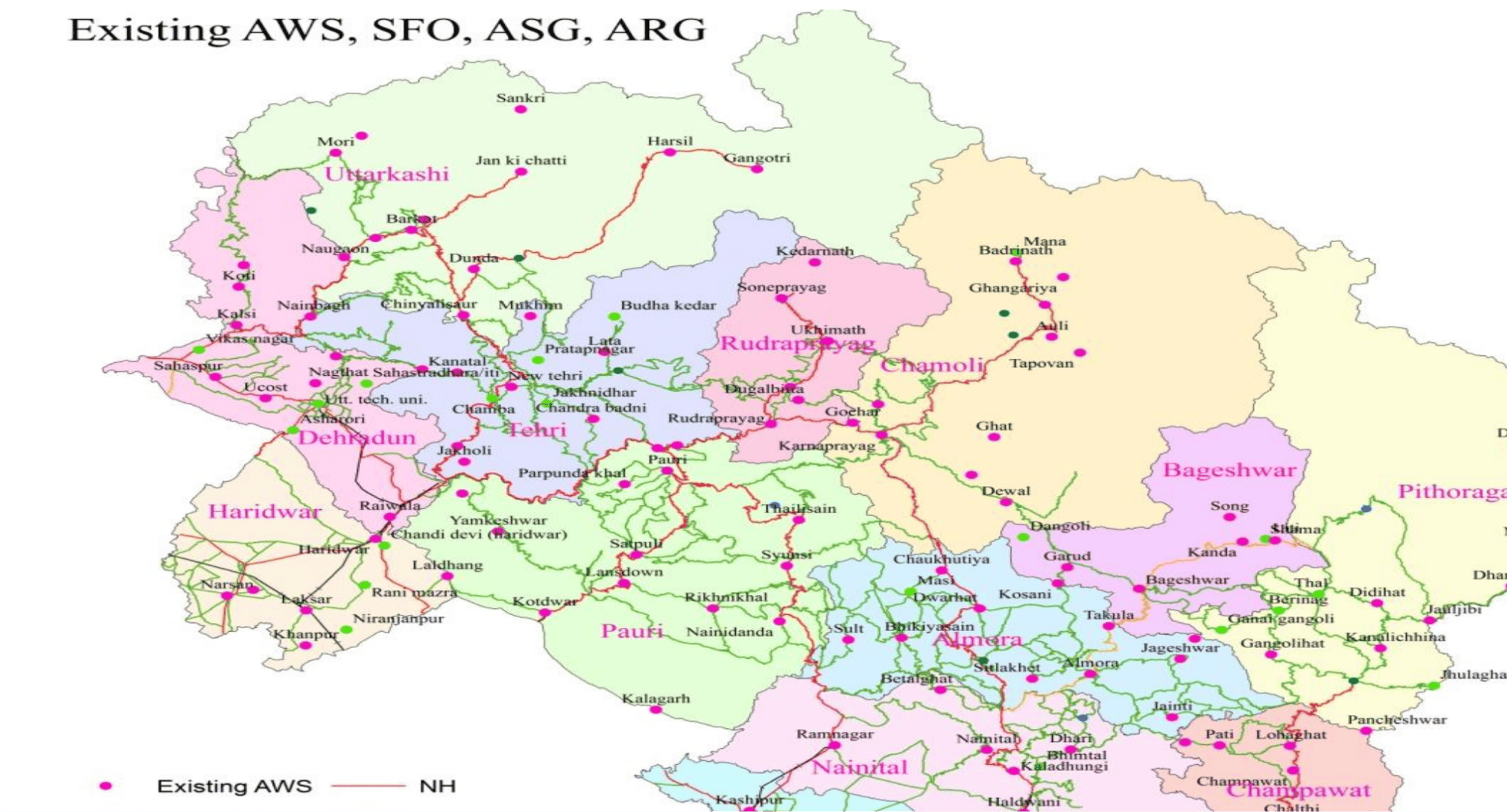

To add to that, India Meteorological Department (IMD) stations with rain gauges that could have determined how much rain struck Dharali before the floods were simply too far away. The Automatic Weather System (AWS) station in Hershil, for instance, is 7 km from Dharali, while the next closest station, Gangotri, is 18 km. This is perhaps why the floods have brought into question the IMD and the Central Water Commission (CWC)’s preparedness in the form of early warning systems for extreme weather events in the Himalayas.

Former Ministry of Earth Sciences (MoES) secretary Madhavan Rajeevan took to X to say that “a comprehensive, multi-hazard early warning system—coordinated across all key stakeholders is urgently essential to minimize future loss of life and property”.

Immediately after the floods and debris descended on Dharali main market Tuesday afternoon, the Uttarakhand State Disaster Management Authority said a ‘cloudburst’ was the cause. However, IMD Tuesday night clarified that none of its stations had recorded a ‘cloudburst’ in Dharali. The MoES, according to a reply in Parliament, describes a ‘cloudburst’ as an event when over 100 mm of rain falls in a small region (20-30 sq km) within an hour.

“The caveat is that in Dharali’s case, there is a lack of manual or automatic weather stations in the region that could confirm the rainfall rate,” said Akshay Deoras, research scientist at the National Centre for Atmospheric Science, University of Reading.

“Observations from nearby rain gauges are indicating much less rain, which is why the theory of ‘cloudburst’ is being ruled out,” he told ThePrint.

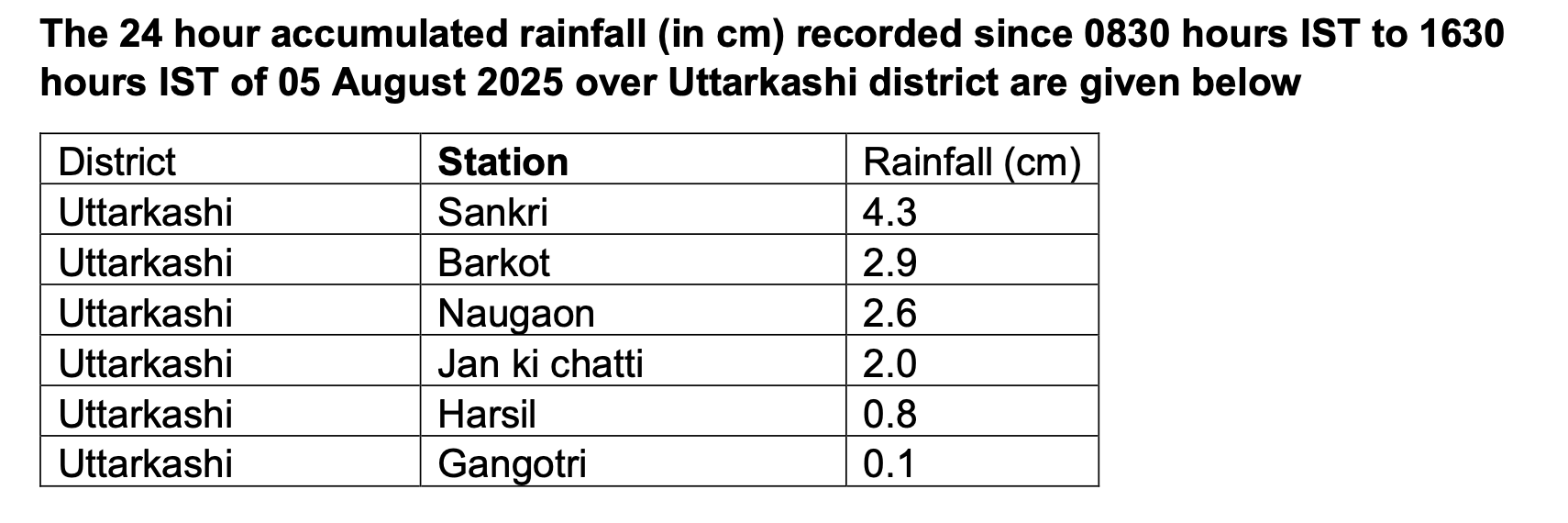

To gauge rainfall data, IMD has six stations in the Uttarkashi district of which Dharali is a part—Sankri, Barkot, Naugaon, Jan ki Chatti, Gangotri, and Hershil. The highest of these is Gangotri station, located at 3,000 m above sea level. But none of these stations, on 5 August, recorded what could qualify as a ‘cloudburst’ by IMD’s definition.

According to Mahesh Palawat, vice president of meteorology and climate change at SkyMet Weather, the contrast in rainfall in the hills is huge, and far-away automatic weather stations may fail to capture it sometimes.

“In mountainous areas, there could be 100 mm rain in an hour in one area, but barely 2 km away it could be 30 mm of rain,” said Palawat. “So it is difficult to ascertain without any data from where the rains and flooding actually occurred.”

IMD director M. Mohapatra, too, told ThePrint that while the agency predicted heavy to extremely heavy rainfall in Dharali and nearby areas, it could not confirm a ‘cloudburst’ due to lack of available data.

Also Read: In flash floods-struck Uttarkashi, rescue ops continue under constant threat of ‘more landslides’

The story behind the floods: other theories

Another theory put forth by experts like Deoras with regard to the floods in Dharali is that heavy rainfall could have led to a glacial lake burst in the higher terrains. Glacial Lake Outburst Floods or GLOF events have been seen earlier in India, like in Sikkim in 2023.

“There is a good chance that one or more glacial lakes or related features aloft got ruptured due to heavy rainfall and associated landslide, and picked up mud and debris,” said Deoras.

Videos of the devastation caused in Dharali emerging on X show a heavy flood of water mixed with mud, debris, trees, and rocks crashing down onto the village in Uttarkashi from upstream. A glacial lake outburst would explain the size and immediacy of the flood.

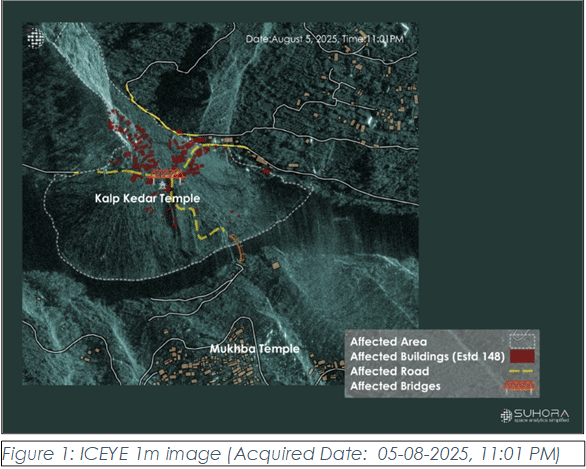

However, global satellite company Suhora Technologies on 7 August said the floods were not caused by a glacial lake burst. It said it used Satellite Aperture Radar (SAR) technology to analyse data from ISRO’s National Remote Sensing Centre in Hyderabad and confirmed there are no glacial lakes upstream of Dharali village.

Using satellite data, Suhora was also able to show that 16 hectares of area was affected by the floods, 148 buildings were impacted, and one bridge suffered damage.

Both Palawat and Deoras, emphasised that even without a ‘cloudburst’, it was Dharali’s slope and terrain that contributed to the impact of the rains. Heavy rains, flash floods, and mudslides in Uttarkashi are not ‘uncommon’ during this period as monsoon activity weakens over the plains and moves to the Himalayas, explained Deoras.

Palawat added that Dharali’s slope added to the danger.

“The ‘cloudburst’ may have happened much higher at 12,000 ft above sea level, and Dharali is at 8,000 ft. Even this slope of 4,000 ft makes a huge difference to the intensity of the water flow,” he said. Adding, “The canal is very narrow, and a lot of trees and mud could have been uprooted and swept along with the water.”

The promise of Doppler Weather radars

Uttarakhand and Himachal Pradesh and extremely flash flood-prone areas due to the hilly terrain as well as proximity to the Himalayas.

To ensure better forecasting for extreme weather events, MoES said in January 2023 that it would install more Doppler Weather radars in Uttarakhand. The statement quoted Union minister Jitendra Singh as having said, “By 2025, the entire country would be covered in Doppler Weather Radar network to predict extreme weather events more accurately.”

These Doppler Weather Radar systems are able to capture accurate information about weather phenomena, including rain and clouds. As of December 2024, there were 39 Doppler Weather radars in the country, of which 3 are in Uttarakhand. While each DWR has a range of 100 km, none of them fall within Dharali’s range.

According to Palawat however, there should be DWR systems every 10 km in places like Uttarkashi that are prone to flash floods and rains. “DWRs are good mechanisms for accurately predicting extreme weather events, and could have probably given 2-3 hours of preemptive warning for events like Dharali,” he said. “But in mountains, DWRs don’t always work properly because their networks are hindered by the hills around.”

Without enough AWS stations or DWR stations in the state, and the challenges of establishing them in mountainous regions, an expert ThePrint spoke to suggested other sources of gathering data for extreme weather events in the Himalayas.

Another solution, which researchers from the Kerala State Council for Science, Technology and Environment (KSCSTE) proposed in May this year involved nowcasting heavy or extreme rainfall events using early microphysical signatures of cloud development. This, they suggested, would work as a building block for effective early warning systems.

“It is crucial to invest in adaptive infrastructure and establish more monitoring stations in the Himalayas and their upper reaches. Enhanced surveillance and early warning systems are vital,” said Anjal Prakash, clinical associate professor (research), Bharti Institute of Public Policy at Hyderabad’s Indian School of Business (ISB). “In their absence, we also need to look at innovative approaches such as satellite imagery, remote sensing, and sharing data with global partners too.”

(Edited by Amrtansh Arora)

In Pictures: Cometh the hour, cometh the man: NDRF personnel brave nature, terrain to reach landslide-hit Bhatwari