Chhatrapati Sambhajinagar: A ‘nala’ evokes the image of a stinking drain choked with garbage. Yet, the word didn’t originally mean that—it was supposed to be a stream, or a seasonal river.

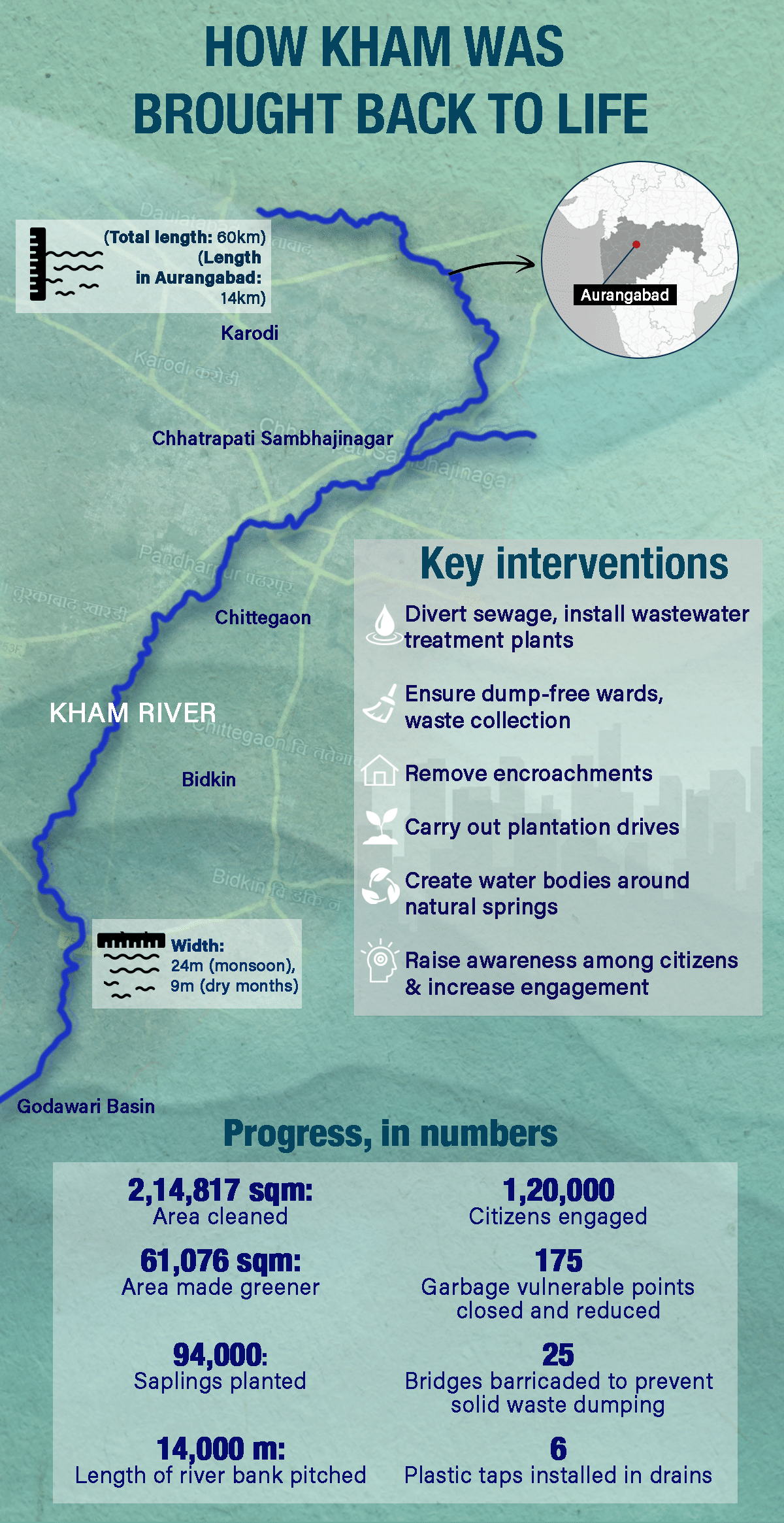

Kham, a 60 km tributary of Godavari that originates in Maharashtra’s Chhatrapati Sambhajinagar, was always such a waterway. But, as it meandered through the city and flowed downstream through the district, it was reduced to an open drain.

That is. Until recently.

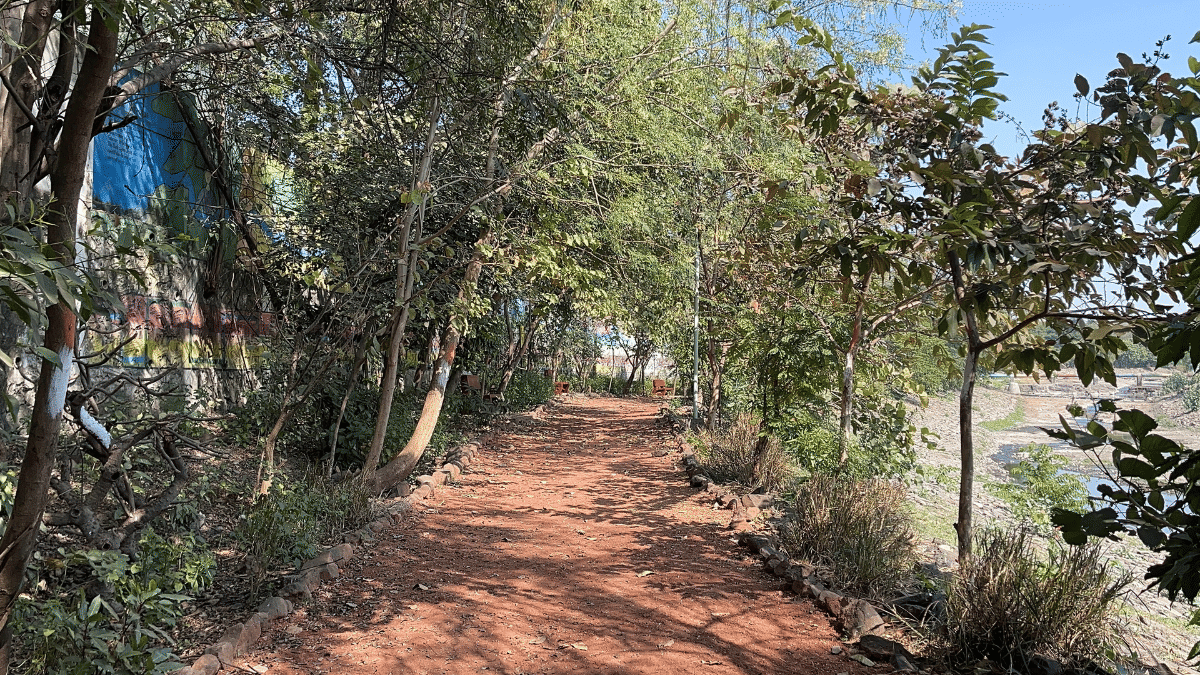

Persistent efforts over the past few years have revived the river. Fresh water now flows through the state’s tourism capital, and spaces created along its banks are full of life, reclaimed by city dwellers. There’s a dedicated track for joggers and cyclists, a women’s gym, a children’s play area and benches under tree canopies.

It’s difficult to imagine what this stretch looked like less than a decade ago. Where children now play and yoga groups gather, there once stood heaps of waste so foul that people could barely walk through the area.

Flowing quietly through the historic city, more recognisable by its original name ‘Aurangabad’, Kham was a river forgotten. Its banks served as dumping grounds, and its waters were blackened by sewage and waste, even as the city around it drew tourists to UNESCO World Heritage Sites Ajanta and Ellora Caves and monuments like Bibi ka Maqbara and the Panchakki Mill from medieval India.

“Our generation knows that it was once a river because we have lived in the days when the river flowed with less trash in it. But I doubt that today’s kids even know that it was once a river,” said Kishoresinh Ingale, a 64-year-old driver who has worked in the city for two decades.

“The smell, especially near bridges, was unbearable. These bridges passed over the nala, which would often be dirty and full of all kinds of waste,” he added.

Also Read: Beas River used to be tame. Why it is turning angry now

A turning point at the bridge

Kham’s revival began in 2016 when the Confederation of Indian Industry (CII), a local company Varroc Engineering and the Cantonment Board identified a highly polluted stretch near a historical bridge. The spot, which connected the cantonment area with the rest of the city, was also a symbolic entry point into Aurangabad, particularly for those arriving from Pune.

“When we came in 2016, we could not cross this area. There were mounds of waste and the smell felt like we were going to fall sick. We started out by picking up trash. 6,000 tractors were filled, mainly with plastics,” Saurabh Jadhav, a Varroc Engineering employee who manages the River Kham Eco Park, told ThePrint.

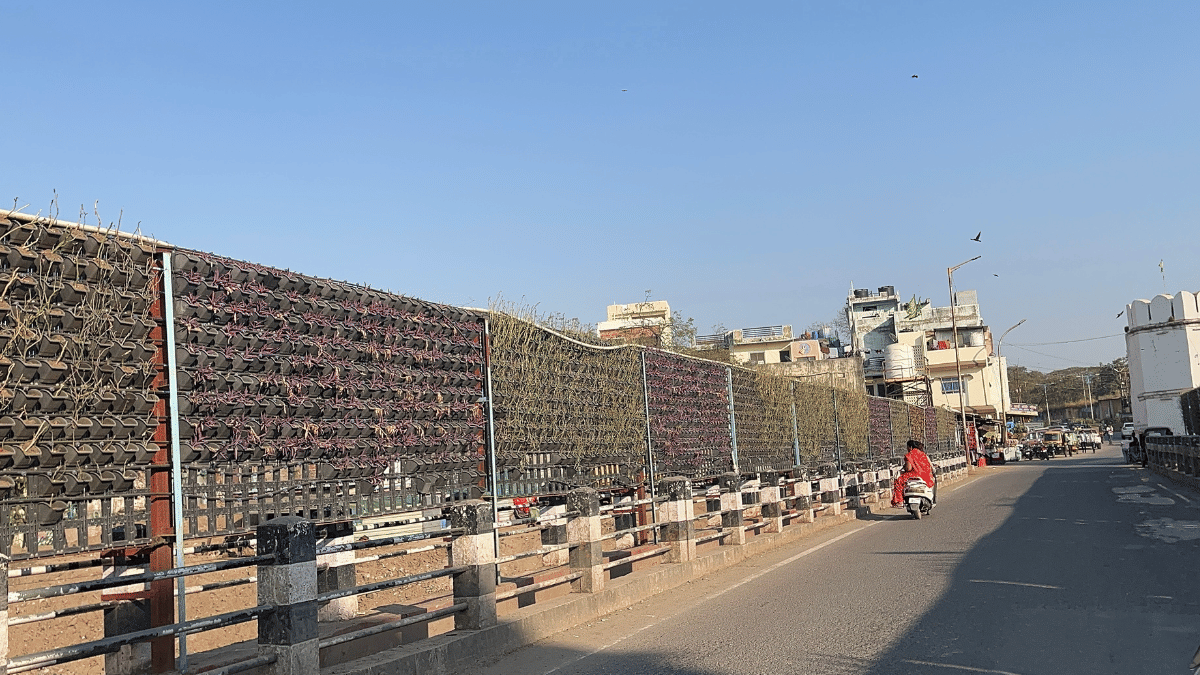

Other interventions to clean up Kham near the bridge were modest but experimental. Funded by Varroc under its corporate social responsibility (CSR) initiative, a “green bridge” technology was introduced to control odour, treat limited quantities of water and reimagine the space as a riverfront rather than a dumping zone. Green bridge systems involve the use of plants and other natural materials to filter and clean water.

But the rainy season quickly exposed deeper, systemic problems.

Every year, tonnes of solid waste were flushed into the river, piling up against these green bridges until the water’s pressure washed them away. It became evident that cleaning a 500-metre stretch was futile without addressing what was entering the river upstream and across the city.

Mapping the problem

By 2019, the project took a decisive turn as the municipal corporation and non-profit Ecosattva Environmental Solutions got involved. What followed was a six-month diagnostic phase using GIS (geographic information system) mapping, drone-based surveys and extensive fieldwork. The team mapped 14 kilometres of the river in the city and 8.8 kilometres of a stormwater drain feeding into it.

The findings were revelatory. The study identified 249 sewage discharge points flowing directly into the river. Nearly 12 percent of the riverbed in the city was covered with solid waste, largely concentrated near bridges, it found.

“Bridges provide really easy access for dumping waste. Our survey found that most of the areas near bridges in the city–there are some 10 bridges across the river and 88 across stormwater drains– had most of the waste. To combat that, barricading the bridges was the answer,” Gauri Mirashi, chief executive officer and co-founder of Ecosattva, told ThePrint.

Interviews with residents, municipal officials and past clean-up groups found other entrenched problems: broken sewer lines, encroachments along the banks and waste management practices that inadvertently pushed garbage back into stormwater drains.

A community survey with a sample size of 700 locals revealed another troubling disconnect.

“Our survey revealed that only 36 percent of residents even knew that Kham was a river,” Mirashi said, adding: “To most, it was simply a nala to be avoided.”

Also Read: How Chenab went from the river of love to the restless ticking time bomb

Time for action

Armed with data, the Chhatrapati Sambhajinagar Municipal Corporation, the Cantonment Board, Ecosattva and Varroc Engineering developed a phased five-year plan anchored around four pillars.

The first was ‘circularity’: stopping solid and liquid waste from entering the river. This meant improving doorstep waste collection and segregation, installing plastic traps and barricades at bridges, and diverting sewage flows into the underground sewer network.

Waste audits revealed an unexpected insight – almost 40% of the trapped waste was textile material. This led to the creation of a textile recovery facility by Ecosattva to turn a pollutant into a resource. A decentralised sewage treatment plant at Siddharth Garden in the city was also set up to treat a significant volume of wastewater before it could reach the river. The facility treats about four million litres of wastewater daily.

Municipal Commissioner G Sreekanth, who assumed office in 2023, told ThePrint, “We have tapped the nalas (stormwater drains) before they enter the river and installed treatment plants. Untreated sewage no longer flows directly into the Kham. The water flowing in the river today is treated water.”

The second pillar focused on ‘risk readiness’, particularly flooding. For the first time, the Kham’s red line – a 100-year flood line – and blue line – a 25-year flood line – were digitally demarcated and integrated into the city’s development plan. This legal recognition offered protection against future encroachments.

“In the last six months alone, we removed nearly 8,000 to 9,000 encroachments across the city,” Commissioner Sreekant said.

A flood-line is a perceived line on the ground that represents the edge of water as a river swells during a flood. The concept is similar to a floodplain.

Physical interventions followed – mechanical cleaning of the river, dredging, desilting, widening of the river channel and pitching of banks using stones sourced locally from infrastructure projects in the city. “What’s important to note here is that large-scale concrete channelisation was avoided to preserve the river’s natural character,” the Commissioner said.

The third intervention centred on ‘blue and green infrastructure’, reimagining the river and its drains as a connected ecological and social network. Sixteen riverfront sites were developed along the Kham, including a dense urban forest, an amphitheatre built using upcycled tyres, and ponds created around 16 newly discovered freshwater springs – evidence that the river’s hydrological systems were still alive beneath years of neglect.

“And so, at the riverfront, 16 little spaces have been created,” Mirashi said.

“As the cleaning was happening. These 16 freshwater springs were identified. All we did was build little ponds around it. And now there are these freshwater bodies. So, all of these spaces have been created with a dual purpose. One is, of course, to have a constructive utilisation of the riverfront. But also, to create spaces for people to interact with the river,” she added.

On freshwater springs, Commissioner Sreekanth said, “Freshwater springs reflect the groundwater health of the rivers. When groundwater recharge improves, springs revive, and the river follows naturally.”

Thousands of trees, too, were planted, and pathways were built from demolition and construction debris collected from different parts of the city. This indirectly prevented solid waste from being dumped into the river.

“There is no concretisation along the Kham, only trees, stones, and natural materials. The riverbanks are being restored for birds and ecology, not merely for human activity. This is not just a beautification project, it is ecological restoration,” Commissioner Sreekanth said.

Engaging the community

Perhaps the most challenging transformation was cultural, making ‘community engagement and identity-building’ the fourth pillar of the project.

It wasn’t an easy task. For instance, in the initial stages of the project, the Kham River Eco Park neighboring the Cantonment Board was made available to schools and colleges. But the sewage problem hadn’t been addressed till then, so it meant that no one wanted to visit the park because of the persisting stench.

This problem was resolved after the sewage treatment plant was funded and installed by the municipal corporation at Siddharth Garden. It became operational in early 2025.

The Siddharth Garden nala, Mirashi explained, is the largest stormwater drain feeding into the Kham. It carries a major share of the city’s sewage.

“Once the STP came in, it became a pleasant place. In May, at 2 pm, we had teacher training sessions outdoors. It was nice, shaded and pleasant. We’ve been getting requests for the venue. We’ve had yoga groups come in, nature walks, birding trails. We’ve even hosted stand-up comedy and concerts,” Mirashi said.

“Very recently, we had a World Diabetes Day celebration with a local organisation called Udaan. There were 600 people. We also had a school that held its annual fest at the Kham,” she added.

A task force for daily vigil

Originating from the Jatwada Hills on the southern edge of the Satpura range, the Kham flows through the city before passing downstream through villages in the district and joining the Godavari at Nath Sagar near Paithan. Seasonal by nature, it swells during the monsoon and thins out in the dry months.

“A seasonal river should be dry in the non-rainy season, that is its natural state. But this river was flowing for 365 days, not because of rain, but because of sewage. Treating at the fag end does not solve the problem. You have to treat the source,” Commissioner Sreekanth said.

Since regular monitoring was essential to maintain the gains, a dedicated task force led by Asadullah Khan (63), who works as Officer on Special Duty with the municipal corporation was created.

Khan, who originally worked in the waste management department of the corporation, was part of a previous attempt by the civic body to clean up the river. At the time too, then municipal commissioner Astik Kumar Pandey had appointed Khan as the head of a task force.

Khan retired in 2023, but was brought back immediately by Commissioner Sreekanth to help the cause.

Every morning at 6am, Khan’s 17-member task force – comprising corporation officials – shows up at various places in the city where the river flows to work on widening, dredging, desilting and stone pitching of the banks.

“When I was young, we used to live here in Banewadi. My mother used to come to wash clothes at the river and I used to tag along,” Khan told ThePrint, recalling a time when the river was clean enough for daily use.

To dredge the river, Khan said, his team “removed all the garbage by scooping it out manually – plastics, textiles, tires, tubes, wooden scraps and other things among them”.

The task force has worked every day for the last six years and is now focused upstream around stormwater drains that lead to Kham.

“These drains, although narrow, still carry little amounts of waste that reach the Kham, which then takes it forward. Therefore, they need to be tackled,” he said.

Khan said locals contribute to the cause by pitching in funds anonymously.

Despite the transformation, Khan believes the work is not complete. “It has reached 90% success. People still throw waste into the river. There needs to be a growing understanding regarding the importance of preserving city rivers. I will continue working towards the complete revival of the Kham,” the 63-year-old added.

Scaling up the vision

With the urban stretch of the river stabilised, the ambition has expanded.

A four-party memorandum of understanding (MoU) has grown into a nine-party collaboration, bringing in the district administration along with the forest and irrigation departments.

The vision to revive Kham now extends to the entire 60km length of the river through the district. Work is already underway in upstream and downstream gram panchayats to replicate waste and sewage control measures.

“The Kham shows that rivers can recover if we stop abusing them. What you see today is the result of sustained, everyday work, not a mere one-time clean-up,” Commissioner Sreekanth said.

The Kham River Restoration Mission won the $100,000 St. Andrews prize for Environment last year. The organisers, University of St. Andrews in the UK, said the project won the prize because it didn’t just work on reviving the river, but also helped transform people’s attitude to it.

Work to revive the second river in Aurangabad has also begun. Sukhna, a 5.3km seasonal river, originates in the district and flows through the city’s old industrial area. Over the years, it too met the same fate as that of Kham.

“Work on Sukhna river began in September. It will take some time but we will achieve a similar result as we did with Kham,” Sreekanth said.

Rishi Agarwal, a Mumbai-based environmentalist and co-founder of Mithi River Sansad, told ThePrint that restoring urban rivers meant more than conservation.

“When you treat sewage at a reasonable level, with decentralised STPs, the rest of the process can be done through bioremediation within the river itself. The poetic and aesthetic need of rivers amidst our cities needs to be appreciated far more than just plain environmental or ecological value,” he said.

(Edited by Prerna Madan)

Also Read: Teesta now flows to kill. How the river forgot to forgive

Thx for well well-articulated and detailed article…We have hope for other rivers