New Delhi: In the Indo-Gangetic Plain, reportedly among India’s most polluted regions, state pollution control boards (SPCBs) are largely funded by fees collected for issuing no objection certificates (NOC), consent to operate and consent to establish polluting industries, a new study has revealed.

On Thursday, the Centre for Policy Research released its latest paper in a series of studies examining the health, efficiency, and constitution of SPCBs in the Indo Gangetic Plain, which is afflicted with severe air pollution, and considered the most polluted region, reportedly responsible for nearly half the pollution-related premature deaths in the country. In 2019, The Lancet estimated 2.3 million deaths in India were caused due to pollution.

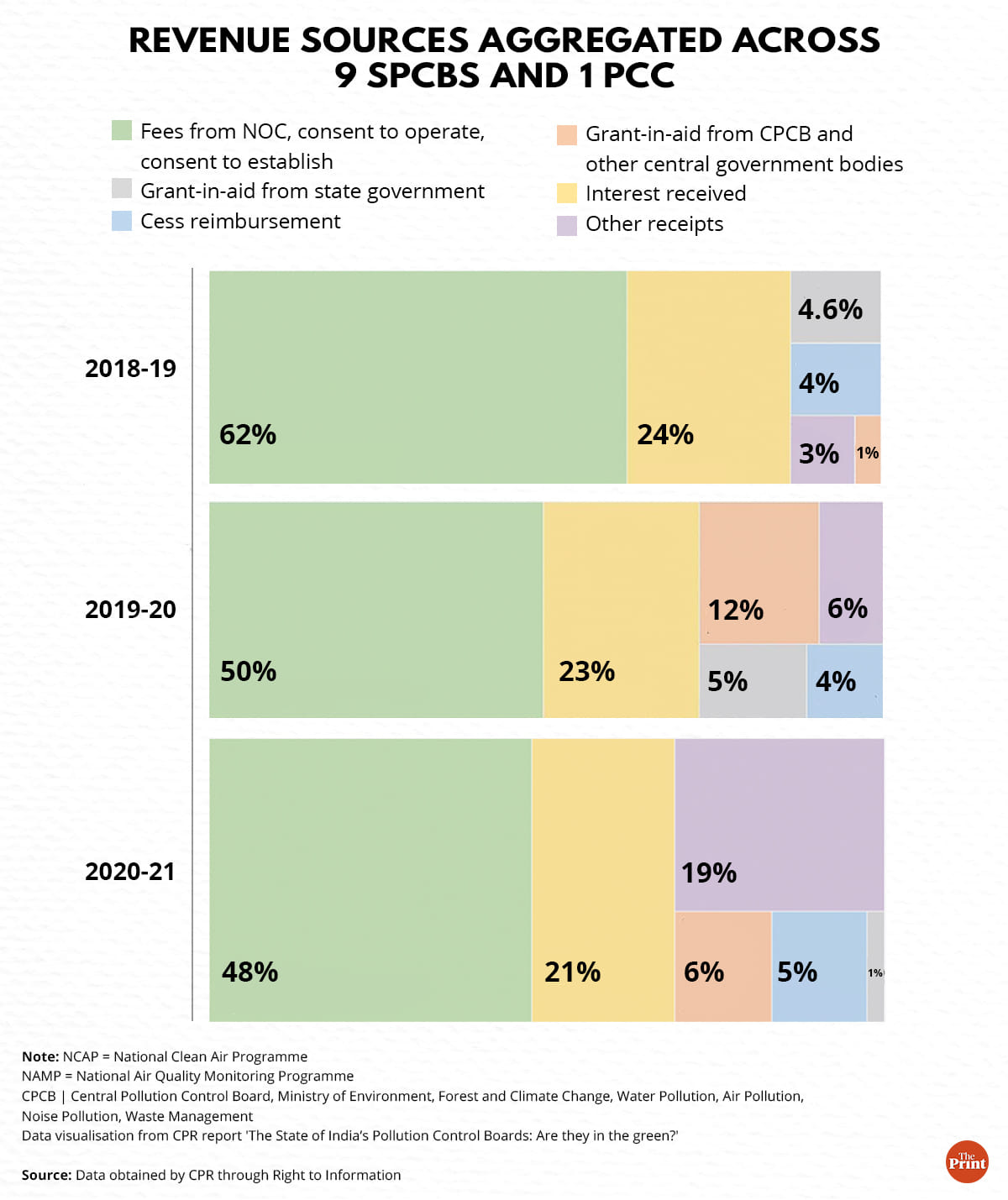

The latest report found that between 2018 and 2021, nearly 50 per cent of revenues generated by nine SPCBs and one pollution control committee (PCC) came from issuing polluting industries NOCs, and granting consent to establish and operate.

“The overreliance on consent fees as an income source coupled with the lack of internal technical capacity means many Boards outsource regulatory functions such as inspections to third parties paid for by Industry. This raises questions around conflict of interest and the ability of the SPCBs to effectively regulate,” the paper said.

What’s more is that the 10 SPCBs and PCC were not “under” funded, but a majority, in fact, consistently turned over a surplus, “with many struggling to spend the entirety of the amount they collect through fees and other sources”. Instead of investing in infrastructure, manpower, or equipment, the SPCBs invested the funds in fixed deposits, the paper claimed.

A conservative estimate by CPR of the amount invested by the SPCBs and PCC in such deposits amounts to Rs. 2,893 crores. “The interest earned from these investments plays a significant role in the fiscal health of the SPCBs,” the paper added.

Grant in aid from the government is unpredictable, ranging from one per cent in 2018-19 to 12 per cent the year after, to six per cent in 2020-21.

“We see that in the absence of un-tied funding from the government, the leadership of the Boards focus most of their energies on revenue generation and less on planning expenditures necessary to meet their mandate beyond consent management,” the CPR paper stated.

ThePrint has reached the chairman and member secretary of the Central Pollution Control Board (CPCB) on email for comment. The copy will be updated once a comment is received.

The creation of pollution control boards was made mandatory under the Water (Prevention and Control of Pollution) Act, 1974. Their mandate under the Act includes “planning, monitoring, surveillance, research and development, and education and training of pollution control”.

Also read: State bodies ‘ill equipped’ to handle air pollution in ‘most-polluted’ Gangetic plain, finds study

‘Don’t have fiscal integrity to carry out tasks efficiently’

The paper released Thursday, follows three others which had found that apart from being understaffed, SPCBs lack technical expertise and are mainly made up of government officials and local authorities, who may be polluters themselves.

Thursday’s paper, titled ‘The State of India’s Pollution Control Boards Are they in the green?’ adds to the previous findings, illustrating how SPCBs don’t have the fiscal integrity to carry out their tasks efficiently.

The study looks at SPCBs in Bihar, Chhattisgarh, Delhi, Haryana, Jharkhand, Punjab, Rajasthan, Uttar Pradesh, Uttarakhand and West Bengal.

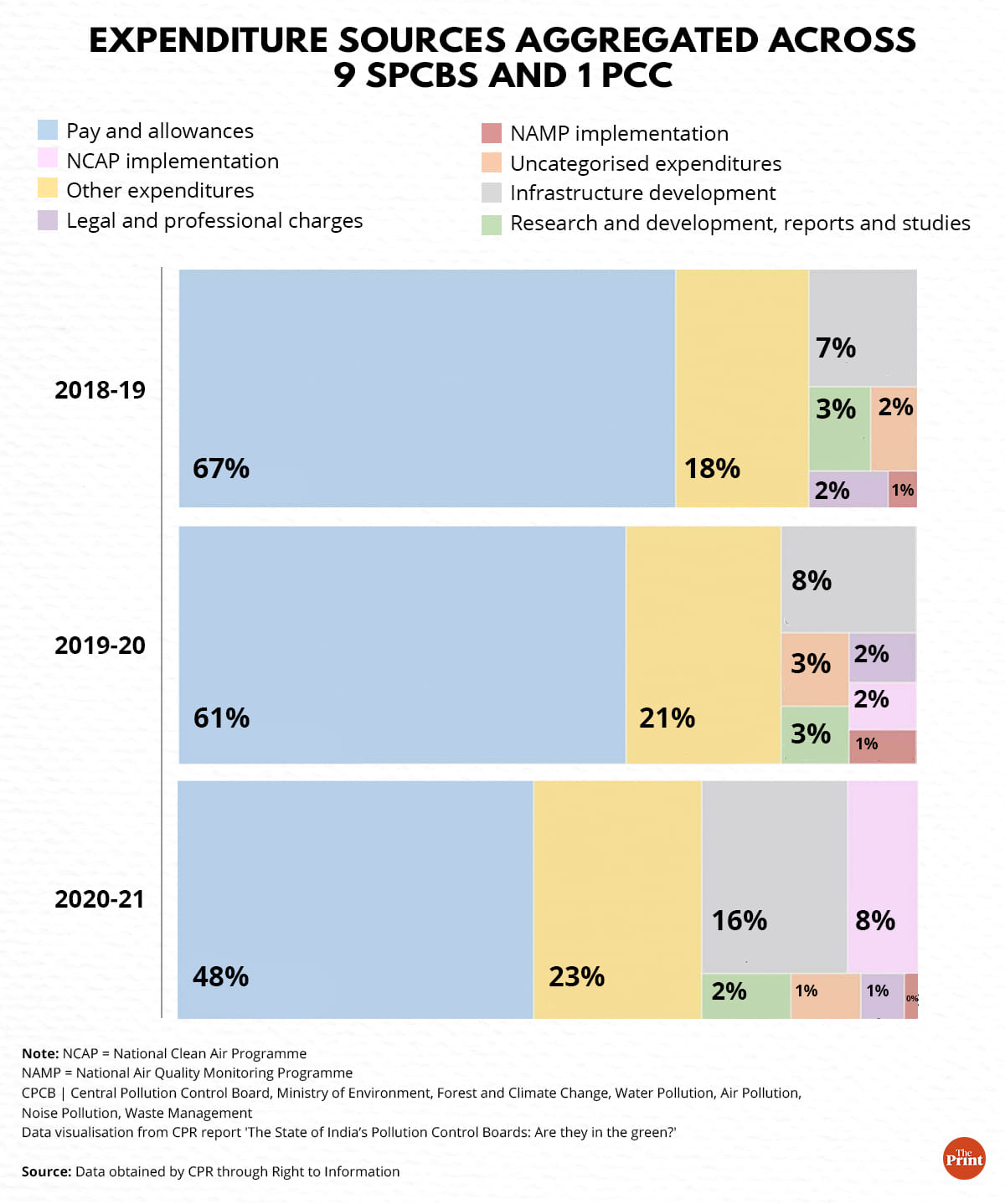

Of the 10 SPCBS and PCC, Bihar had the largest proportion of expenditure towards the National Clean Air Programme (NCAP). Delhi and Haryana did not receive funds under NCAP for the duration of the study, and five of nine SPCBs didn’t make any expenditure towards the NCAP within the first two years of its implementation.

The NCAP is a scheme to reduce air pollution across 131 “non-attainment” cities, for which 472.06 crore (as revealed in Parliament) has been allocated by the Centre as of June 2022. Non-attainment cities are those where the air does not meet ambient air quality standards.

A bulk of expenditure by SPCBs is going towards pay and allowances, the CPR analysis shows, although the proportion has come down from 67 per cent in 2018-19, to 61 per cent in 2019-20, and 48 per cent in 2020-21.

“This is not the trend we observe with the actual amount of funds being spent underpay and allowances, with six out of nine states actually spending more under this category in 2020-21 than in 2018-19. This is indicative of increased spending in other categories over the study period,” the paper said.

Research and development have occupied barely three per cent of funds from 2018 to 2021, and barely two per cent was spent on legal and professional fees, which “include charges paid for legal services, audits and the costs paid to external consultants for analysis of air and water quality”, the paper added.

One reason why funds are not properly used is because of fear of leadership “being questioned” if large sums are authorised for equipment, manpower, and research, the paper claimed, citing interviews with SPCB officials.

“Given that the SPCBs are unable to meet their statutory mandate effectively under the current fiscal and regulatory conditions, there must be greater debate around what form SPCBs take and what role they have in a forward-looking regulatory regime that aims to substantially reduce air pollution from current levels by leveraging modern approaches and regulating at the level of airsheds, not States,” the paper said.

(Edited by Poulomi Banerjee)