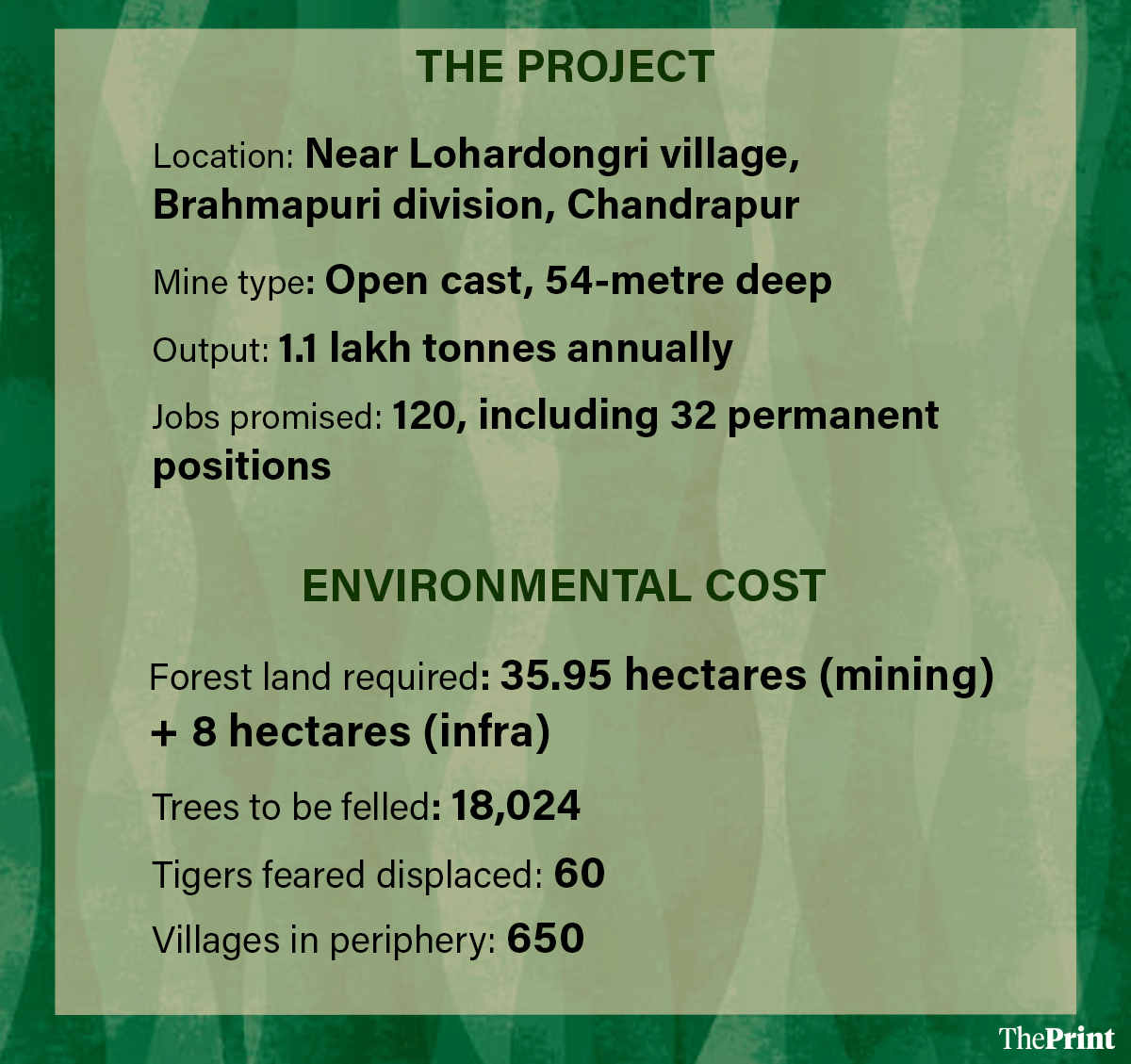

Mumbai: On one side—35.95 hectares of forest land, 18,024 trees, 60 tigers and 650 villages.

On the other—a 54-metre mine, 1.1 lakh tonnes of iron ore a year, few roads and 120 jobs.

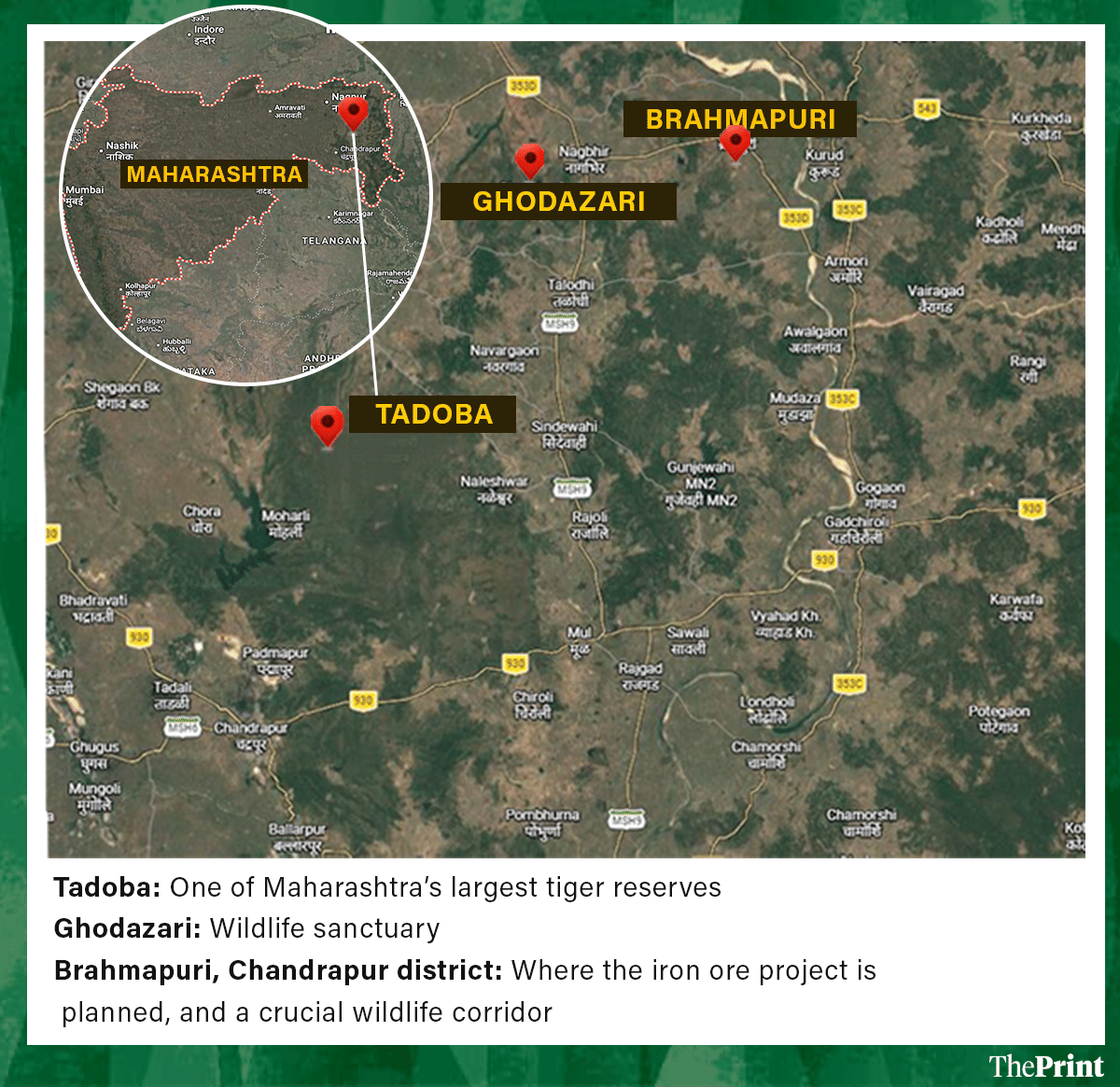

The Maharashtra government’s approval for an iron ore project on a wildlife corridor near the Tadoba–Andhari Tiger Reserve and the Ghodazari sanctuary has set off alarms. Environmentalists are concerned that mining in the Brahmapuri division of Chandrapur district would lead to felling of over 18,000 trees and possible displacement of 60 big cats there.

The State Board for Wildlife (SBWL), led by Chief Minister Devendra Fadnavis, on 6 January cleared the proposal for the project despite strong objections from an expert committee formed by the board.

With activists protesting against the project for over a month, the Bombay High Court last week took suo-motu cognisance of the matter and appointed advocate Gopal Mishra as amicus curiae. The court told Mishra to file a petition within two weeks.

Maharashtra Additional Chief Secretary (forests) Milind Mhaiskar told ThePrint that the role of SBWL is recommendatory in nature.

“The proposal was examined by the SBWL in detail, and due consideration was simultaneously given to recommendations of the technical committee constituted specifically to assess the ecological and wildlife-related implications of the proposed mining project,” he said. “The technical committee, after comprehensive evaluation, observed that sustainable mitigation of potential man-animal conflict in the region can be effectively achieved in the long term by strengthening existing wildlife corridors, and by bringing additional areas of the tiger landscape under the protected area network of the state.”

He added that the technical committee recommended the declaration of a new wildlife sanctuary encompassing approximately 35,000 hectares—an area nearly a thousand times larger than the project footprint—covering the critical corridor between Ekara Conservation Reserve and Ghodezari Wildlife Sanctuary. The SBWL, he said, accepted the recommendation, considering the project proposal only subject to this stringent and substantive precondition.

“It is therefore clarified that the SBWL has not ‘approved’ the project, as has been erroneously portrayed in certain sections of the media. The recommendation was conditional, and premised on significant conservation commitments. Furthermore, the final authority to approve or reject such proposals vests solely with the National Board for Wildlife (NBWL), which will take an independent and informed decision in accordance with applicable law and established procedures,” Mhaiskar said.

State forest minister Ganesh Naik did not respond to multiple requests for comment till Tuesday.

Also Read: India’s tiger population likely to jump by 10% in new census. ‘But, running out of space’

What is the project?

The project, allotted to Nagpur-based private steel firm Sunflag Iron and Steel Company Ltd, requires diversion of 35.95 hectares of reserved forest land. According to estimates by the expert committee appointed by SBWL, 18,024 trees would need to be felled for mining in Brahmapuri.

Environmentalists believe 5-6 tigers roam the forests that may be destroyed for the open cast mine, and fear that the overall impact on the surrounding region could displace 60-odd tigers there. This could potentially increase human-animal conflict in and around 650 villages in the periphery, they said.

The project, according to the committee’s report, promises generating employment for 120 people, of which only 32 will be permanent positions.

“How is the government neglecting the man-animal conflict that is rising in this region? Mining project in a tiger corridor is very dangerous… It will increase the conflict. That’s why we are opposing the project,” said Bandu Dhotre, a Chandrapur local, an environmentalist, former wildlife warden of Chandrapur and former member of SBWL.

Chandrapur in Vidarbha region of Maharashtra has dense forests—a contiguous large stretch that makes for the tiger reserve and patches across the district. Activists believe the district has 250 tigers in total, many of whom move from forest to forest in search of prey and water. The Brahmapuri division acts not just as a tiger corridor, but is also known for a variety of tree species—bahawa, tendu, teak, awala and mohua, among them.

Sunflag Iron and Steel Company Ltd (SISC), one of India’s largest steel producers, was allotted the project by the state last month. The company currently operates an integrated iron ore mining and steel manufacturing plant at Bhandara, some 100 kilometres from Brahmapuri.

The plant produces 5 lakh tonnes of steel annually—nearly five times the planned extraction in Brahmapuri—most of which is supplied to automobile makers Tata, Volvo, TVS, Maruti Suzuki, Bajaj and Harley-Davidson, the committee’s report said.

In Brahmapuri, the iron ore project is planned close to Lohardongri village. It would require diversion of nearly 36 hectares of forest area for extraction, and an additional 8 hectares will be needed for ancillary infrastructure and road construction. The mine will require digging to 54 metres and is projected to have an output of 1.1 million tonnes over 12 years, less than 1 lakh tonnes annually.

“There is so much mining happening anyway at Gadchiroli–Surjagad. Then, why are they behind this small mine,” Dhotre asked, referring to operations about 100 km away.

SISC did not respond to multiple requests for comment till Tuesday.

Former state environment minister Aaditya Thackeray waded into the controversy and wrote to Union Environment Minister Bhupendra Yadav last month.

“These projects are detrimental to both the forests they are located in as well as the wildlife that inhabits these forests. I implore you to protect these forests and the wildlife…I humbly urge you to reconsider and reject these projects at the National Board for Wildlife. The future of our forests and fauna is in your hands now,” Thackeray wrote.

Panel flagged ‘irreversible damage’

The iron ore project, though allotted this year, has been under consideration for some time.

The SBWL, in October 2023, constituted a three-member expert committee of Chandrapur chief conservator of forests Dr Jitendra Ramgaonkar, and members of the state wildlife board Pravin Singh Pardeshi and Poonam Dhanwatrey.

The committee submitted its first report to the state board on 24 January 2024. After being directed to provide more details, it submitted a comprehensive report in August 2024.

In strongly-worded observations, the committee said in the final report: “Any mining in this forest will cause irreversible damage to the environment and wildlife, loss of large tree cover, and immense pollution of air and water. Forest fragmentation will increase human–large carnivore conflict and heighten threats to humans, habitats, and wildlife.”

The report highlighted that landscape fragmentation due to development projects such as irrigation and road widening had resulted in boxing large carnivores and forcing them to “co-exist with people; leading to the highest level of human-large carnivore conflict”.

The committee did not recommend the project, but it also did not advise against it explicitly. Instead, it made some recommendations should the project get clearance from the national wildlife board.

It noted that the “project should only be reviewed on the grounds of sustainability, cost benefit ratio, and maintaining integrity of wildlife corridor”. It also suggested that NBWL should consider approving the project only if the forest stretch from Ghodazari sanctuary to Ekara Conservation Reserve is declared a wildlife sanctuary. The area of the planned mine must be included in the proposed sanctuary, it said.

Dr Ramgaonkar told ThePrint that any development project would damage the area’s ecology. “It is very clear that ecologically, it is a very important area. The only saving grace is that, if our recommendations are implemented, then, to an extent, it will mitigate the damage. But, see… any mining project will have a negative impact and it has to be equated with national priorities, which we cannot comment on,” Ramgaonkar said.

The report also mentioned local concerns, but did not specify how many residents the committee had consulted. Some locals believe they will secure permanent employment but fear wildlife conflict, pollution and health impacts, it said.

Activists fear escalating conflict

In Tadoba, the protected zones span 1,700 sq km and are home to around 92 villages within a largely continuous forest landscape.

But the Brahmapuri division, where the project is planned, is not protected under the Forest Conservation Act. It covers another 1,100 sq km area and includes about 650 villages across scattered forests.

This region is also crucial because of its proximity to Ghodazari Wildlife Sanctuary, some 20 km away from the Tadoba reserve. There are water bodies here that serve as sources for both tigers and local communities, according to Dhotre.

The expert committee’s report described the site as a “crucial tiger corridor connecting the source population of tigers in Tadoba-Andhari Tiger Reserve to Brahmapuri-Gadchiroli landscape and to the northern tiger bearing forests”.

In a letter to Union Environment Minister Bhupendra Yadav last month, Dhotre said that while the core and buffer zone of the Tadoba reserve housed 90 tigers, the Brahmapuri division was home to another 65 adult tigers, including 43 females, 59 cubs and 12 sub-adult tigers. The Lohardongri area specifically is home to two female tigers (one with a cub) and three adult males, he said.

Beyond tigers, the area harbours 8 to 10 leopards, 5 to 7 bears, wild dogs, wild cats, hyenas, deer, rabbits, monkeys, wild boars and several bird species. The area is rich in medicinal plants, fruit trees, water sources, and lakes.

Locals fear forest disturbance could intensify man-animal conflict.

“In 2025, 47 deaths were recorded in tiger attacks in Chandrapur district. At least 18 people were killed in tiger-related conflicts in the Brahmapuri division within a year, with 10 tigers having to be captured and removed,” Dhotre said.

He explained that as the tiger population increases and cubs mature, they require new territories. With shrinking forests, they have nowhere to go.

“We want our government to release us from this trouble. We are being attacked and people here live in fear and anxiety. For the last 15 years, there has been a lockdown-type condition here,” he said.

Dhotre insisted that his opposition to mining was not about development versus environment. “The question of development comes if there is no other place for iron ore, and Lohardongri is the only source. But 100 km from here, mining is going on (in Gadchiroli region),” he said.

For Ramgaonkar, the economic aspirations of people in the area must also be considered when discussing environmental issues.

“As a technical department, our role is to mitigate the damage. So, that is what has been done. And between environment and development, a balanced view needs to be taken,” he said.

This is an updated version of the report.

(Edited by Prerna Madan)

Also Read: Maharashtra’s Kham shows even ‘dead’ urban rivers can be revived—here’s the blueprint