Junnar/Shirur: Vikas Bombe watched helplessly as a leopard grabbed his 13-year-old son, Rohan, on 2 November. There was nothing he could do to save the boy.

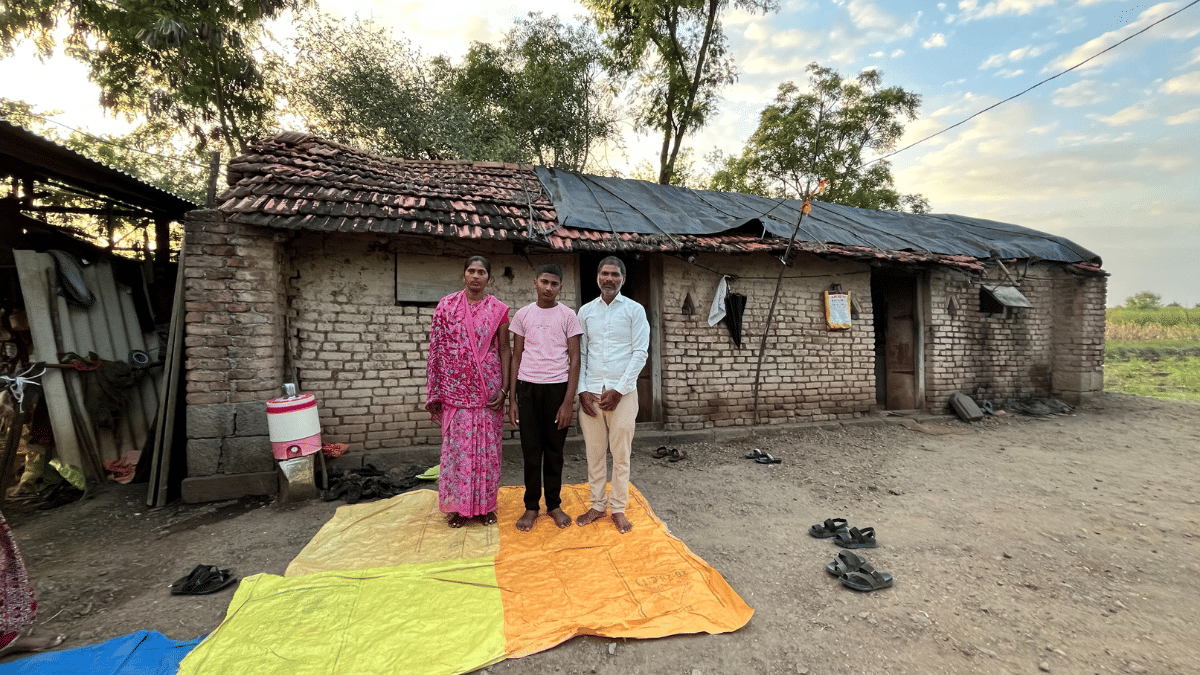

“I was right there, just 20 steps away. When I ran towards the leopard, it turned him over and dragged him into the field,” Vikas told ThePrint, standing outside his mud-and-brick house.

“I carried him out in my arms. I was drenched in his blood. His slippers are still in the open field where he was attacked. You can find his clothes in the sugarcane field where it dragged him,” he added.

For months now, terrified villagers like Bombe in Junnar and Shirur talukas on the outskirts of the bustling city of Pune have been living in complete fear that a leopard may emerge from the sugarcane fields and attack them.

At least four people—three children and one elderly person—have been killed in the past two months in Junnar alone, after being pulled by leopards from the edges of their homes.

Three of these deaths have occurred in the span of just twenty days.

In the neighbouring districts of Nashik and Ahilyanagar, five deaths each have been recorded since September, taking the toll across the three adjoining regions to 14 in just two months.

The increasing leopard attacks have sparked protests in the region, pushing the authorities to take immediate action, but villagers say it isn’t enough.

When Rohan was killed, anger spread through the village like wildfire. Villagers set a ranger’s patrol car ablaze on the night of the incident.

On 4 November, locals from Khed, Ambegaon and Shirur tehsils blocked the Pune-Nashik Highway to protest the increasing number of leopard attacks in the region. They also set fire to a forest department’s base camp in the village.

The deaths in Junnar and the subsequent protests prompted Maharashtra Forests Minister Ganesh Naik to visit the Bombe family on 12 November.

“I have given the order to shoot on sight if a man-eater is seen,” Naik told the media. “We have already bought 200 cages here and have asked for 1,000 more. The captured leopards will be sent to Vantara and some African countries that have asked us for leopards.”

“We are seeking technology that will alert the villagers about leopard movements. With the use of satellites and the help of AI, if the leopard is captured on camera, a siren will go off for a radius of 3 km,” he added.

Chief Minister Devendra Fadnavis told the media on 4 November that there are currently around 1,300 leopards in the Pune and Ahmednagar districts, and this situation needs to be handled cautiously to safeguard both human lives and protect animals.

“We urge the Centre to give us permission to capture and put the animal down, if necessary, in cases where it becomes a man-eater,” he said.

Terror of the Big Cat

As sugarcane farming flourished in this belt over the past two decades, with vast acres of land covered under the tall, dense crop, leopards began descending into the tall sugarcane fields in many of these villages.

The unique topography of the land, due to these plantations, enriched with plenty of water, shelter and a variety of food, proved to be an ideal home for their increasing population.

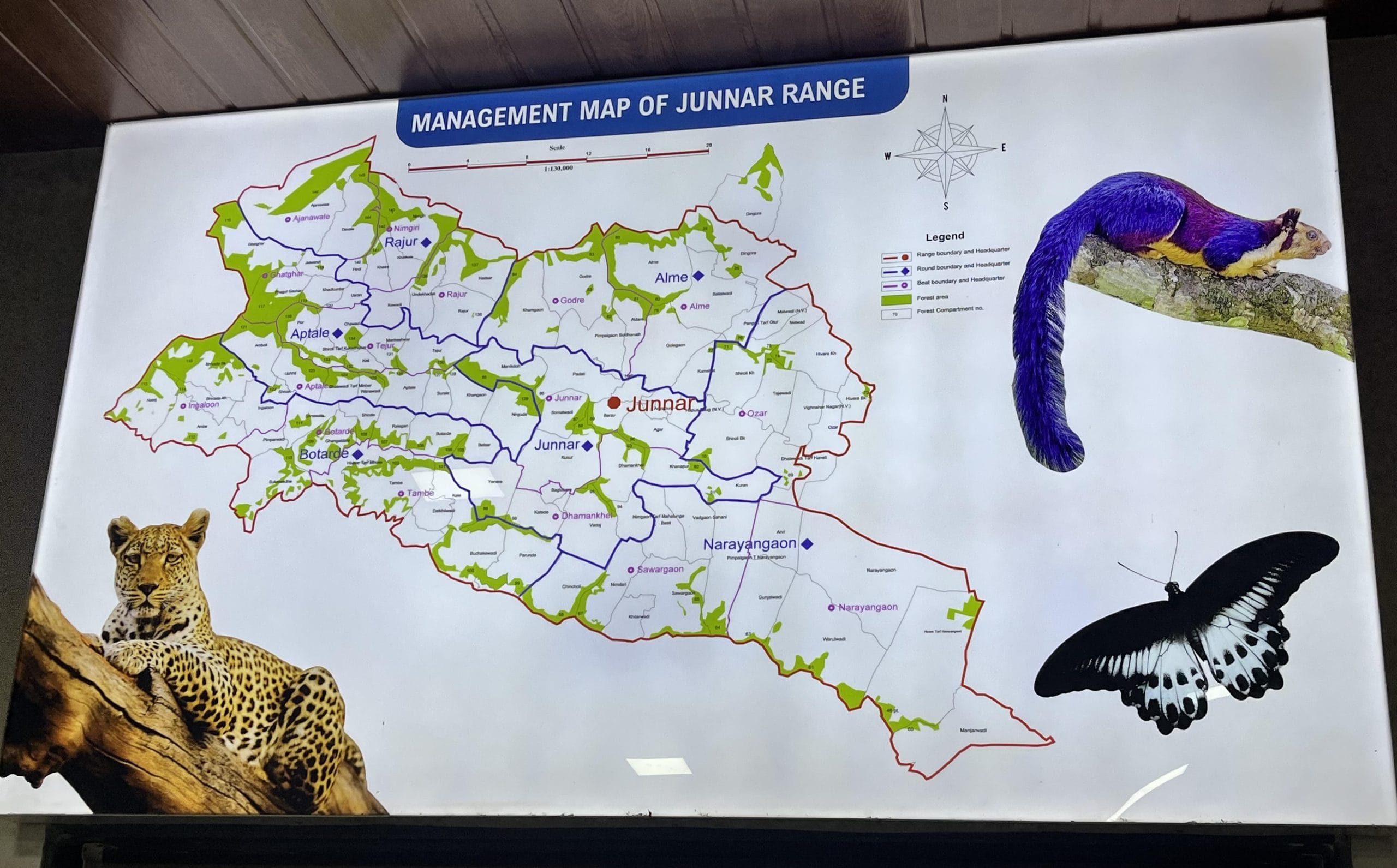

“The man-animal conflict began in the 2000s when the leopards moved down south into the sugarcane fields in search of food, water and cover as sugarcane fields are the best hiding spot for these big cats,” Range Officer Pradeep Chavan told ThePrint.

Leopards also began moving out when their natural habitat was destroyed because of the construction of dams in the region. Chilewadi Dam, Manikdoh Dam and Pimpalgaon Joge Dam were built in Junnar and Shirur talukas in the late 1990s and early 2000s. This, coupled with routine forest fires, forced the wild animals to move.

“Three divisions—Junnar, Nashik and Ahilyanagar—are surrounded by the Sahyadri ranges with large forest lands inhabited by the leopards. In the 1990s, in the Junnar and neighbouring talukas, around four to five dams were built, destroying the leopard habitat,” said Chavan.

A survey by Chavan found that 56 people had died in leopard attacks in the past 25 years. His survey was split into two periods: one from 2000, when the incidents began, to 2016; and the other from 2017 to 2025.

He discovered that while 25 people were killed in the first 16 years, 26 people died because of leopard attacks in the next eight years alone, suggesting that the deaths had doubled.

A forest officer, who did not want to be named, said the death toll had doubled in the past eight years because the leopard population had increased.

“If there are 500 leopards in the region today, and even if we consider an equal ratio of the genders, there are 250 nar (males) and 250 madri (females). Each madri (female) gives three to four cubs. Even if we consider three cubs, the total goes up to 750 new leopards,” the officer said.

Leopards are highly adaptable. With a change in their habitat, their food chain shifted too. Instead of wild prey, the animals now survive on livestock, dogs, poultry and small creatures found around homes.

With farmland carved into tiny plots of two to three acres per family, all it takes is one leap for a leopard to cross from cane to courtyard.

Just 20 days before Rohan’s death, his cousin, Shivanya Bombe, only five-and-a-half years old, was attacked almost the same way.

“I was in the kitchen when Shivanya entered, asking for a bottle of water. When I asked her what for, she said, ‘Baba (grandfather) is working in the field, I will get him some water’. That was the last time I spoke to my daughter,” said Shivanya’s mother.

Arun Bombe, Shivanya’s grandfather, told ThePrint, “She had come to give me a bottle of water. She sat a few steps away from me and was playing in the field as I was doing some chores when the leopard attacked her from behind, held her neck and shook her twice.”

According to Deputy Conservator of Forests Prashant Khade, leopards do not deliberately target humans.

“Leopards come for chicken, goats, dogs and other livestock. These animals are alert and can save themselves and take cover. If we look at the statistics in the region, the leopards only attack people sitting on the ground from behind. Humans are not as alert and, therefore, become an easy target,” he told ThePrint.

What the forest department is doing

With the number of leopard deaths mounting, Maharashtra’s forest department has stepped up efforts to handle the problem.

Range Officer Chavan said forest authorities use heat-sensing thermal drones to detect the body heat of leopards and monitor their presence. Villagers also alert them when they spot leopards in their areas.

When they detect the presence of leopards, forest authorities survey the land for paw prints and trap the animals in specially designed cages with bait like goats, dogs or chickens. The cages are placed either at the edge or deep into the dense fields.

“The cages have a grilled wall in the centre and two boxes on either side. We keep a prey – a goat, dog or chicken – locked on one side, and the other side open for it (leopard) to enter. The empty box has an elevated step,” said Chavan.

“Once he enters the box and steps on the elevated plank, the lever opens from the top, and the back door of the cage is suspended down, locking the leopard inside,” he added.

The caged leopards are then taken to Manikdoh Leopard Rescue Centre in the heart of the Junnar forest range.

“Only three types of leopards are taken to Manikdoh: cubs who have strayed away from their mothers, accidental, or those knocked down on the highways by speeding cars, and narbhakshi (man-eaters),” Chavan told ThePrint.

The Rescue Centre, established in 2007, is currently home to 30 leopards who receive both temporary and long-term care. It is equipped with doctors, medical facilities, a hospital and 250 sq m cages.

A senior forest officer, who did not want to be named, told ThePrint, “The government should bring stronger schemes, send teams and form committees which can recommend the next steps.”

He suggested sterilisation as one option, but that is currently banned because leopards are protected under Schedule I of the Wildlife (Protection) Act (WLPA) of 1972, which mandates the harshest penalties for offenses against these species.

The forest department needs the permission of the Principal Chief Conservator of Forests (PCCF) to sterilise an animal. And permission is only granted when the animal becomes a man-eater or endangers humans. So far, permission has yet to be granted by the PCCF.

“In the olden days, due to hunting, a lot of species were endangered; therefore, in 1972, WPLA was introduced to protect these species,” said Chavan.

Too little, too late

But some families said the government’s efforts were too little, too late.

Shivanya’s father, Shailesh Bombe, said cages and cameras were set up only after protests by villagers.

“Two days after her death, the forest department stepped in only after the protests. Cages and cameras were brought in, but too late,” he told ThePrint.

Rohan’s father still struggles to speak of the day his son died. “Our children are not safe in our own backyard,” he said.

Just 10 days after Shivanya’s death and 10 days before Rohan’s death, Bhagubai Jadhav, a 72-year-old woman in the neighboring Jambut village, was brutally killed by a leopard.

“By the time we found her, it had eaten her body waist up, including her hair, leaving only a partial side of her face intact,” a Jambut village resident told ThePrint.

She went into the field, not far from her house, in the morning when a leopard attacked her, held her by the neck and dragged her body for almost a kilometre.

“Our last three generations have lived in this village, and not once did we have to worry about leopards or any other animal harming us. We want to go back to the time when we lived free from this fear,” Rohan’s father told ThePrint.

“We wait for her to come back home every day,” an emotional Divya Bombe, Shivanya’s mother, added.

Range Officer Chavan said the leopard that attacked Rohan is the same one that attacked Shivanya and Baghuba had been killed. Officers laid traps and found the leopard in the vicinity of the three homes.

“They called us at 12:30 am to show us the carcass. It was shot three times in the head,” said Vikas Bombe, Rohan’s father.

Chavan said forest authorities had been tracking the leopard’s paw size and other markings since Shivanya was killed.

“Upon his death, when we matched his paw measurements with the data we had collected, we found that it was the same animal responsible for all three deaths,” he said.

The families and locals are not convinced that the leopard shot was the same one that attacked and killed Shivanya, Baghubai and Rohan.

“We see leopards walking around our house every other day. How do we know for sure that the one killed is the same one who took the life of our daughter 20 days ago?” Shivanya’s mother told ThePrint.

Officers are overwhelmed as every day feels like a new challenge. As night falls, villagers retreat indoors, children no longer play outside, and farmers avoid stepping out before sunrise. What was once quiet farmland is today a landscape living in fear.

For many in Junnar and Shirur, like the Bombe family, the rustling of sugarcane, a sound that they grew up with, is now deeply unsettling. It no longer means it’s just the wind.

“We have lived in this fear for 25 years now. We no longer want promises. We seek justice in the form of immediate action. We want a plan. And we want one before another child is taken,” said Vikas Bombe, Rohan’s father.

(Edited by Sugita Katyal)

Also read: 3rd death in a month: Tiger attacks lead to safari halt in Bandipur & Nagarhole reserves